What is work? And how can we think better about work? Like many other things, we more or less know what work is when we don’t think about it too hard. But when we try to think a bit more deeply, or a bit more systematically, it becomes harder to figure out. So in this piece, we’ll be looking at the philosopher Hannah Arendt, whose exploration of the vita activa, or “the active life”, is a useful way to start getting a handle on the role that work plays in human life.

Who was Hannah Arendt?

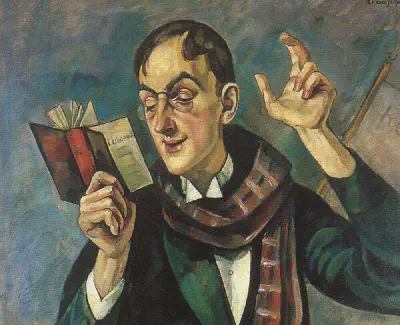

In her book The Human Condition, Arendt contrasts the vita contemplativa, or “the contemplative life”, and the vita activa, or the “active life.” For Arendt, human life involves both contemplation and activity. And this dual commitment to both thinking and doing was reflected in her own life. Arendt was not only a political theorist and a philosopher, but she was also an educator and an activist who engaged actively in politics.

Hannah Arendt was born in Hanover, Germany in 1906. She studied with some of the most significant philosophers working in Germany during the first half of the 20th century. After studying at the University of Marburg with Martin Heidegger, she briefly enrolled in classes with Edmund Husserl, the founder of the movement in philosophy called phenomenology, a rich philosophical tradition that explores the textures and structures of human experience. Arendt then wrote her PhD in Heidelberg under the supervision of the philosopher Karl Jaspers. Her thesis, completed in 1926, was on the concept of love in the work of the philosopher Saint Augustine.

By this time, Anti-Semitism was on the rise in Germany. And Arendt, who was herself Jewish, realised that a future in Germany was increasingly unviable. When the Nazi party came to power in 1933, she fled—first to Prague, and then to Paris. In Paris, she worked for several Jewish refugee organisations until the outbreak of the Second World War. She was briefly imprisoned in 1941, after which Arendt fled France, this time to New York.

In New York, Arendt continued to write and teach, eventually settling and becoming a US citizen. She published The Human Condition in 1958.

Although she held several visiting positions at universities both in the US and globally, Arendt resisted the temptation to take on a tenured role in a university preferring the freedom of combining writing, teaching, politics and other work. Arendt died in New York in 1975, her book The Life of the Mind, the sequel to which she saw as a part of the same project as The Human Condition, still unfinished.

Contemplation and activity

The Greek philosopher Aristotle saw the vita contemplativa as the ultimate aim of human life. For Aristotle, theōria or contemplation was far more important than praxis or practical activity (see the article here). In other words, the ultimate justification of practical activity was that it should help support contemplation. Doing better is valuable, Aristotle claims, only to the extent that it helps us with thinking better.

These days, however, we are likely to see things in reverse. If we seem like we are getting too theoretical, people are likely to call us out and say, “That’s all fine, but what practical use is any of this?” What matters for us is action rather than contemplation. Our own position, in other words, is the precise opposite of that of Aristotle: the ultimate purpose of thinking better is doing better.

For Arendt, this reversal of the hierarchy between thinking and doing is one of the most important transformations in Western thought.

Perhaps the most momentous of the spiritual consequences of the discoveries of the modern age […] has been the reversal of the hierarchical order between the vita contemplativa and the *vita activa.* [1]

Perhaps the most famous example of this reversal is in the work of Karl Marx. In his Theses on Feuerbach, Marx complains that we are too hung up on contemplation and insufficiently attentive to “sensuous human activity.” And he challenges us to ask what it would be to think about human life not just as something to theorise about, but instead as something that we can actively shape. Marx ends his Theses with the famous claim that:

The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it. [2]

Thinking differently about the world is all very well. But for Marx, the ultimate justification of philosophy lies in whether it allows us to behave differently, or to act differently.

Seeing human being whole

For Aristotle, there is a hierarchy between thinking and doing, with thinking having the upper hand. Marx turns this hierarchy upside down and says that doing should have the upper hand. For Arendt, however, the problem is the hierarchy itself. Instead of seeing the vita contemplativa and the vita activa as existing in a hierarchical relationship, she claims that we should instead see them as different aspects of human life.

One reason that Arendt resists these hierarchies is that once you have a hierarchy like this, you commit yourself to the idea that there is one ultimate principle of human life. And when you have decided that human life is governed by a single principle, you have to make everything else fall into line around this principle.

This not only narrows the scope of human life, but also muddies our thinking. Many things matter in human life. Contemplation is good, in and of itself. But likewise, digging the garden is good. So is making a chair out of wood, or baking a cake, or putting on a play. There are many different good things. And if you try to gather them together under a single principle, you miss the complexity and the diversity of human life. So in resisting these hierarchies, Arendt wanted to open the door to seeing human being whole, so that we can start to understand human life in its complexity and its messiness.

Anatomising the vita activa

In The Human Condition, Arendt asks what it means for human beings to act. She defines the vita activa as “human life in so far as it is actively engaged in doing something.” We are not beings who just sit and contemplate. We also do stuff. But human activity is very diverse, so to get a handle on this diversity, Arendt divides this activity into three broad categories: “labour”, “work” and “action.”

With the term vita activa, I propose to designate three fundamental human activities: labor, work, and action. They are fundamental because each corresponds to one of the basic conditions under which life on earth has been given to man. [3]

Labour

At the most fundamental level, we need to provide for our bodily, biological needs. We need to feed ourselves. We need fresh water. We need shelter. Arendt calls this struggle to meet our biological needs labour.

Imagine you are marooned on a desert island. Fortunately, the island has an abundance of good fresh fruit, tasty tubers, and flavoursome rodents to feast on. In the centre of the island is a small spring that provides fresh water. You have everything you need. But to sustain your daily life in this little paradise, you have to put in the time. You have to pick those fruits, dig up those tubers, chase down those rodents, and go back and forth to the spring to gather water. This is what Arendt means by labour.

Before you live too long on your desert island, you realise that the thing about labour is that it is never-ending and interminable. If you want to go on surviving, we have to keep on digging up tubers and chasing down rodents and carrying water.

For Arendt, this means that at some very basic level, we are not free. We are bound to our biological needs, and as these needs will continue as long as we live, so too will the need for labour.

Work

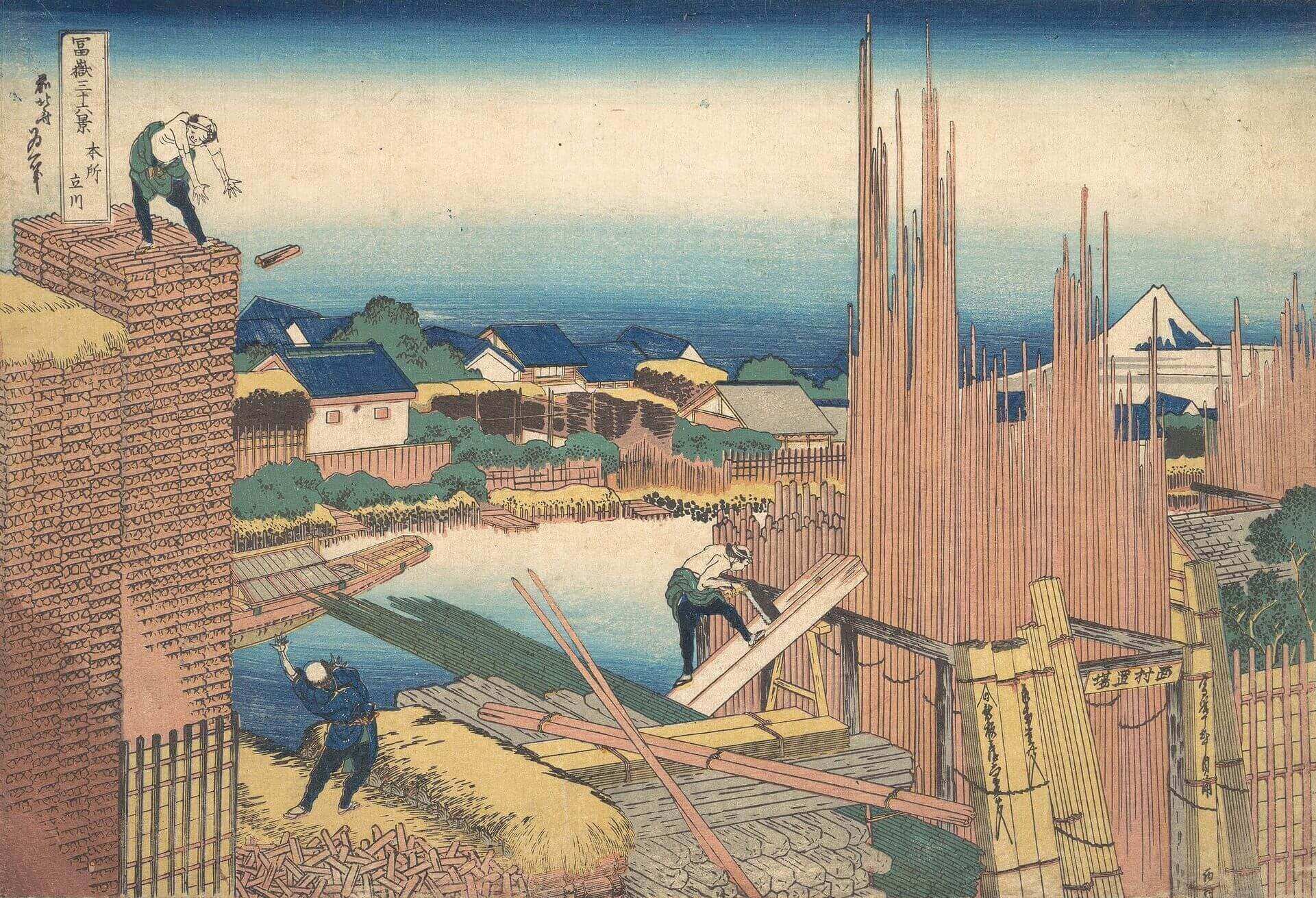

The trouble with labour is that it is cyclical. It doesn’t go anywhere. It doesn’t build anything for the future. It just keeps you ticking along. But human beings also act on the world not just to meet their needs, but to reshape the world, so it can better provide for them. This is what Arendt calls work. Work is about producing something—a result—that will continue to endure in the world after the work is done.

Through work, we don’t just sustain our survival. Instead, we turn the world into a world that is partly human-made. We create objects and institutions that endure. If on your desert island, you decide to build a little hut to live in, then that is work. You spend a few days building, and at the end of it, your world is slightly different from how it was before.

Arendt complains that past thinkers have obscured the distinction between labour and work. They have seen the activity of digging for tubers and the activity of building a hut as the same thing. But work is not just about bare survival. It is about bringing something new into being. Once you have reshaped the world through work, you have won for yourself a degree of freedom. You can sit in your new hut, snug and cosy, and enjoy the benefits of your new shelter, long after the work is done.

Arendt herself knows that the boundary between labour and work is blurred. There are ongoing tasks to sustain the products of your work—the roof needs fixing from time to time—and none of the objects that we fabricate is entirely durable. But the products of our work are capable of outlasting us. And for this reason, work, unlike labour, has a social dimension. If you get rescued from that desert island, it won’t matter to the next castaway that you have laboured to pick and eat fruit. But the house you have worked on will still be standing, and the new castaway can move in.

Action

The third kind of activity that Arendt explores is action. Action is profoundly social. Action is what happens when we come together in society with others, each of us with our own uniqueness, our own talents, our own qualities, and our own concerns, and we try to work out how to refashion our shared world.

If the active life was only about labour and work, nothing would ever change. We’d just keep on remaking the world in the same way as it had always been. Work just replicates the same structures again and again. But action is where change starts to happen. Action is about acting in society with others to change the structures of which we are a part. And this process is fundamentally social. There is no action, Arendt argues, in isolation. There is no action for our castaway.

Action is also where we are most free. When we are labouring, we are caught up in necessity. We are subject to our bodily needs and unfree. When we are working, we free ourselves to some extent from these needs by reshaping the world so that we can enjoy a degree of freedom. But our freedom is still limited. We are still a part of the world that we have inherited, and all of its structures.

It is only when we engage in action that we start to reshape, reimagine and reinvent our shared world. Action is when we say, “Hey, it doesn’t have to be like this. How about we do it this way instead?” Or it is when we take to the streets to protest. Or it is when we get together to rethink our shared world.

Giving birth to new worlds

One way of thinking about this is by thinking in terms of what Arendt calls “natality.” Philosophers are often preoccupied with mortality, by the fact that human beings die. But they pay less attention to the way that human beings give birth to new things and new worlds. Natality is about the every-present possibility of change. It is about the way we can together give birth to newness in the world.

Labour and work, as well as action, are also rooted in natality in so far as they have the task to provide and preserve the world for, to foresee and reckon with, the constant influx of newcomers who are born into the world as strangers.

However, of the three, action has the closest connection with the human condition of natality; the new beginning inherent in birth can make itself felt in the world only because the newcomer possesses the capacity of beginning something anew, that is, of acting. In this sense of initiative, an element of action, and therefore of natality, is inherent in all human activities.

Moreover, since action is the political activity par excellence, natality, and not mortality, may be the central category of political, as distinguished from metaphysical, thought. [4]

For Arendt, this is the highest question of the vita activa. How do we transform the world? What new worlds do we want to give birth to? And when we are asking these questions, we are at our most free.

Discussion questions

- Arendt argues that in the modern era, we have reversed the traditional hierarchy between thinking and doing. What is most important to us these days is action rather than contemplation. But is Arendt right about this? Or do we still value contemplation more highly?

- In your own vita activa, how much of your activity is labour, how much is work, and how much is action?

- Can philosophy help contribute to what Arendt calls “action”—in other words, to changing the structures of which we are a part? If so, how?

- Philosophers think a lot about mortality, the fact that we all die. But how might it change our approach to philosophy if we thought more about natality—the fact that we are all capable of creating new things in the world?

Notes

[1] Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (Chicago University Press 1998). p. 21

[2] Karl Marx, Theses on Feuerbach (see the online version here).

[3] The Human Condition, p. 7

[4] The Human Condition, p. 9

More further reading

Books, articles, and film

One old-but-good book that discusses the philosophy of work, and explores Arendt in some depth, is Herbert Applebaum’s The Concept of Work: Ancient, Medieval and Modern (SUNY Press 1992).

Simon Smith’s introduction to Arendt in the Routledge Critical Thinkers series is well worth a read. Simon Swift, Hannah Arendt (Routledge 2009).

Vita Activa: The Spirit of Hannah Arendt is an award-winning documentary about Arendt. You can find the film website here, and watch it on Amazon Prime and elsewhere.

Online resources

Here’s a good overview of Hannah Arendt’s continued significance from Deutsche Welle.

And this is interesting, on work in a time of Covid-19 and Hannah Arendt.