Wisdom, thinking and doing

Welcome to the second piece in this series on wisdom: what it is and why it matters. In this piece, we’re going to be plunging into the work of Aristotle, one of Ancient Greece’s most profound thinkers, to ask about the relationship between wisdom, thinking and doing.

Wisdom, as we saw in the last essay, is more complex than it first seems. When we say someone is wise, we are not saying they possess just a single quality. Instead, we are suggesting they possess a suite of qualities. To be wise involves, at the very least, some combination of how you think about the world, how skilfully you act, and how effectively you communicate.

In this article, we’re going to look more closely at how Aristotle distinguishes between two of these things: the wisdom that is rooted in our knowledge or understanding (or theoretical wisdom), and the wisdom that is rooted in our action (or practical wisdom).

Aristotle: philosopher of everything

Aristotle was born in Stagira in Macedonia in the year 384 BCE. He later moved to Athens where he studied with Plato. According to the biographer Diogenes Laërtius, Aristotle was quite an oddball. He had small eyes and bow legs, and he spoke with a lisp. He was a pretty snappy dresser: he trimmed his hair short — although the fashion at the time was to have long, flowing locks — and he liked to wear big, elaborate rings on his fingers. And it was said that he was an electrifying public speaker.

Aristotle is one of those philosophers who can feel daunting because he was interested in pretty much everything. He wrote about poetry and politics, about ethics and the nature of the soul. He did research into biology. He interviewed beekeepers to find out about bees, and sponge divers to find out about sponges. He spoke to hunters to find out about wild animals. And he carried out numerous dissections of animals to see how they worked.

This habit of taking things apart to see how they work was something that characterised all of Aristotle’s philosophy. He was obsessed with the idea of systematically studying the nature of things, whatever those things were. So whether he was writing about politics or poetry, ethics or zoology, his approach to problems was to first try and break them down into their constituent parts. And when it came to wisdom, he did the same.

Breaking action apart

In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle explores the question of what it means for a human being to live a good life. What is central to Aristotle’s view of the good life (or, in fact, to any life at all), is the idea that living is an activity. Life is not just a matter of being alive. Instead, it is something we engage in actively.

Life is a kind of activity, and each person engages in activity in relation to those objects and with those faculties that he likes best; the musician, for example, engages in activity with his hearing in relation to songs, the student with his thought in relation to what he studies, and so on in each case.Nicomachean Ethics, 1175a [1]

But if life is a kind of activity, what does it mean to act?

Aristotle breaks down human action into three broad categories. The first is theoria, or contemplation. This is about our knowledge of the world, and our active seeking to understand the world and make sense of it. The second is poiēsis, which literally means “production”, or “bringing forth”, and is related to the word “poetry”: this is about how we produce or bring forth particular things through the use of particular skills. And the third is praxis, or “chosen action.” Praxis is about how we choose to act as we make our way through the world.

You can think of these three kinds of action, more or less, as thinking, making and doing: an example of theoria (or thinking) is getting to grips with Aristotle’s philosophy and exploring the truth or falsity of it; an example of poiēsis (or making) is baking a pie; and an example of praxis (or doing) is choosing how to deal with an ethically difficult situation at work.

Thinking, making and doing

We are used to drawing a distinction between theory and practice, or between thinking and doing. But Aristotle’s threefold distinction between thinking, making and doing may feel unfamiliar. After all, isn’t making a kind of doing? Here we need to do a bit more unpacking.

To understand the distinction Aristotle is making, and to understand more precisely what Aristotle means by praxis, we need to ask what these different kinds of action are for. Every chosen activity, Aristotle says, is for the sake of something. Theoria (thinking or contemplation) aims at something that is beyond the activity itself: we contemplate for the sake of truth or understanding. Poiēsis also aims at something beyond the activity itself: we make an apple pie not just for the fun of it, but also for the sake of having an apple pie. But praxis, or “chosen action”, is different because it doesn’t aim at something beyond the activity itself. The activity is the point. You act well for the sake of acting well, not for some further purpose. And is what makes praxis so distinctive: the end or purpose of the activity is the activity itself.

Philosophical slapstick, and the perils of contemplation

So for Aristotle, we need to think about wisdom in relation to these different kinds of human activity. Wisdom is not just theoretical. It is not just about knowing stuff. There is also a kind of wisdom in making stuff, which we might call skill. And there is wisdom in how we choose how to act, which Aristotle calls practical wisdom or phronesis.

For Aristotle, practical wisdom is an essential part of a well-lived life. This is why he berates the earlier philosopher Thales who, in a famous moment of philosophical slapstick, is said to have fallen down a well when looking up at the stars. Thales might have been pretty smart in some respects, but failing to look where you are putting your feet is foolish. People like Thales, Aristotle comments drily, may know lots of stuff, but they lack practical wisdom and are “ignorant of what is in their own interest” (1141b) [2]. Thales is like the original distracted professor, who is so immersed in contemplation that he fails at the practical business of living—to the extent that it puts his life in danger.

And here, Aristotle makes a fascinating distinction between theoretical and practical wisdom. Theoretical wisdom is about general principles, or the knowledge of things that are stable and unchanging. But practically speaking, our lives are not like this: our day-to-day existences are much more unruly and changeable. So in the hurly-burly of our everyday lives, when choosing how to act, we can’t rely only on a single theory or body of to tell us how to act. Instead, we need a kind of wisdom that can get to grips with uncertainty and change:

Agents must always look at what is appropriate in each case as it happens, as do doctors and navigators. — Nicomachean Ethics, 1104a [3]

Practical wisdom as navigation

This idea of practical wisdom as a kind of navigation is a fascinating one. Imagine that you want to cross the Atlantic, so you go down to the docks to see who is around. You meet two navigators, both of whom are looking for crew. Let’s call them Maisie and Mildred. You get talking to them, trying to decide whom to travel with.

First, you speak with Maisie. It turns out she has impressive credentials. She is a whizz at theory. She has gone to navigator school and even taken a PhD in navigation science from a prestigious university. In fact, she has studied pretty much everything a navigator might need: engineering, meteorology, shipbuilding, fluid mechanics, astronomy and so on. Her boat, the Theoria, is gleaming and new, state of the art. There’s only one down-side: when you chat to Maisie, you casually ask her how many times she has made this voyage. “Oh,” she says with a brilliant smile, “I haven’t. It’s my first trip. In fact, I’ve never been on a boat before in my life…”

You thank Maisie and go and talk to Mildred. She is standing by her boat, the Praxis. It __ seems solid enough, but it is not nearly so shiny as the Theoria. And when you get chatting, Mildred turns out to be a very different kind of navigator. She has no degree and very little schooling. In fact, at the age of thirteen, she bunked off school altogether, stole a neighbour’s boat (the neighbour later forgave her), took it for a couple of spins around the harbour, then sailed it up the coast. After that, she never came home. Mildred is now fifty years old, she tells you, and she has sailed around the world eight times, as well as crossed the Atlantic more times than she can count. This is promising, but Mildred also seems a little strange. When she talks, she lapses into long digressions, telling you salty sea-dog tales about mermaids and whales and spells that quell tempests, things that don’t sound much like accurate theory…

The question is this: whom do you choose to take you across the Atlantic? The theoretically astute Maisie? Or the practically experienced Mildred?

Wisdom in theory and in practice

I don’t know about you, but my money would be on Mildred, however many impressive degrees and qualifications Maisie has, and however weird some of Mildred’s theoretical positions. Because when it comes to knowing how to act, or how to navigate our way through the world, theoretical wisdom is not the most important thing. What is most important is developing a living responsiveness to the changing situations we find ourselves in, a keen attention to the changing winds and tides, and the ability to make just the right choices at just the right time.

For Aristotle, these two kinds of wisdom — the theoretical and the practical — are very different. When choosing how to act, we can’t just take our theories, plonk them down and hope that everything will come out right. Practical wisdom is not the application of general truths to specific circumstances. Instead, it is something entirely different: a knowledge of how to act based on a depth of experience, and on the cultivation of particular dispositions. This is one reason why contemporary philosopher Sophie Grace Chappell (who I’ll be interviewing for Looking for Wisdom in a few weeks’ time) argues that systematic moral theories eventually fail: the application of general principles to specific situations is simply not a good way of choosing how to act wisely.[4]

Wise action involves knowing how to act just now, in this complex unrepeatable situation. Think is the friend who knows just the right thing to say to ease our unhappiness. Or think of the person (and perhaps we all know someone like this) who seems to have an almost magical power to resolve intractable interpersonal disputes. Or think of a hostage negotiator who manages to defuse a complex situation. Knowing how to act is not about the dry business of applying theories to our practical lives. It is the art of developing navigational skill and cultivating the right set of virtues and dispositions so that, when it comes down to it, we will act wisely, whatever circumstance we find ourselves in.

Virtue and contemplation

By now, it might sound as if Aristotle is arguing that practical wisdom is the only wisdom that matters. And this is a common contemporary view. If theory matters at all, we sometimes think, it matters because of how we can put it into practice. Otherwise, it has no use at all. You might not want Maisie as captain. But put both navigators on the same ship, and Maisie’s PhD-level theoretical expertise could usefully inform Mildred’s practical experience, and offset some of Mildred’s more wildly extravagant views about mermaids.

But Aristotle doesn’t elevate practice above theory like this, nor does he justify theory in terms of its practical value. Instead, he takes the opposite path. He argues that practical wisdom, and the cultivation of virtue, are important because without them, we cannot fully be in a position to engage in contemplation. Practical wisdom is a central to what it means to live a healthful, flourishing life. And the ultimate aim of a healthful, flourishing life is theoria: it is to engage in contemplation. Because for Aristotle, there is no better life than one of contemplation.

Discussion questions

- An easy question to start: Maisie or Mildred? Who would you go with? And why?

- For Aristotle, practical wisdom is about particular circumstances, and theoretical wisdom is about general principles. But can the two be divided up so easily? Or does theoretical wisdom also matter for how we choose to act?

- We tend to think that the point of theory is that it should be put into practice. But Aristotle argues the opposite: for him, the point of practice is to provide a strong foundation to our lives, so that we can engage in contemplation. Is there something in what he is saying here?

- Do you know anybody like Thales who has a lot of theoretical wisdom, but very little practical wisdom? And do you know anybody who is the opposite: they have a lot of practical wisdom (they seem to always know how to act) even if they lack theoretical wisdom? If so, whose life seems to go more smoothly? Who seems to be flourishing more?

Notes

[1] Aristotle: Nicomachean Ethics, trans. Roger Crisp (Cambridge University Press 2004), p. 190

[2] ibid. p. 190

[3] ibid. p. 25

[4] Sophie Grace Chappell (published as Timothy Chappell), Knowing What To Do: Imagination, Virtue, and Platonism in Ethics (Oxford University Press 2014).

More further reading

Books and articles

I used the Cambridge University Press edition of the Nicomachean Ethics, but there are lots of editions around, including some freely accessible online.

For a friendly, accessible introduction to Aristotle, try Edith Hall’s excellent Aristotle’s Way: How ancient wisdom can change your life (Bodley Head 2018).

As ever, the Very Short Introductions series from Oxford University Press is reliable. Jonathan Barnes’s book on Aristotle in the series, Aristotle: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press 2001) is an excellent starting point.

And finally, Carlo Natali’s Aristotle’s Wisdom (SUNY Press 2001) is a much more in-depth study of practical wisdom, or phronesis.

Online resources

Here’s a nice video on Aristotle from the School of Life, which gives a breezy, friendly overview of Aristotle’s life and philosophy.

And try this OUP blog on Aristotle and practical wisdom.

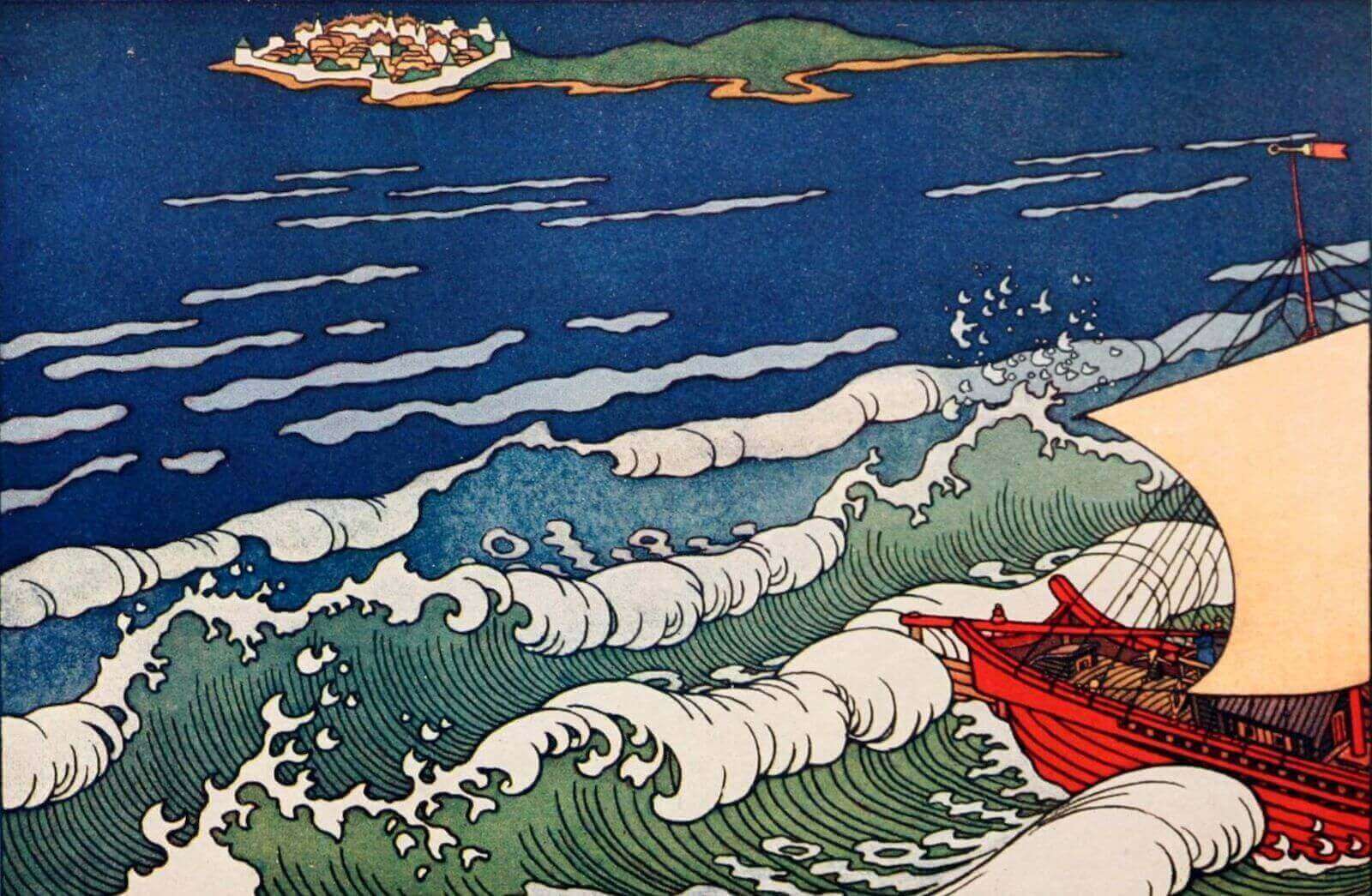

Image: Illustration by Ivan Bilibin From Russian Wonder Tales (1912). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.