The Love of Wisdom, and the Wisdom of Love

Welcome to the final piece in our series on love. In this article, we’re going to be looking at the idea of philosophy as the love of wisdom. And we’re going to ask about whether there is a deeper connection between wisdom and love.

The first person to talk about philosophy as the love of wisdom was the Greek philosopher Pythagoras. The idea that philosophy is the love of wisdom—rather than, for example, the practice of wisdom—puts a bit of a distance between us and the wisdom that we aspire to. We can love wisdom without being entirely wise, just as we can love virtue without being entirely virtuous, or we can love beauty without being entirely beautiful.

But the idea of philosophy as the love of wisdom is also a dynamic one. We are impelled towards that thing that we love. It draws us in, fascinates us, intrigues us. And we want more of it in our lives.

Wisdom’s love

There are two ways of thinking about what it means to talk about the love of wisdom. First, we can see wisdom as an object of love. There are lots of things that we might love: a person, a cat, samosas, mimosas… These things may be more or less worthy of love, but they are all objects towards which our love and our interest are directed. If we understand the love of wisdom like this, then wisdom is simply the object of our fascination, or even our infatuation.

But there’s another way of thinking about the love of wisdom. Because this phrase could also mean something like “the love possessed by wisdom,” or even “wisdom’s love” (in the same way that “the cat of my neighbour” can mean “the cat possessed by my neighbour”, or “my neighbour’s cat.”)

If we understand the love of wisdom in the first sense, with wisdom simply as the object of love, this doesn’t commit us to any particular understanding of wisdom. But if we understand it in the second sense, then this suggests that there is something about wisdom that entails love. So if we understand the phrase “the love of wisdom” as equivalent to “wisdom’s love”, a deeper relationship between love and wisdom emerges. And we can start to see that maybe philosophy is not just about how we think about the world, but it is also about the quality we bring to this thinking: a quality of attention, care, or love.

Love’s wisdom

Even if we agree that philosophy has something to do with love and something to do with wisdom, we might tend to give the idea of wisdom a higher value than love. In this view, love is the means to wisdom, and wisdom as the goal.

But two thinkers in the 20th century reversed the order of these two terms, asking what it would mean to think about philosophy instead as the “wisdom of love,” or as “love’s wisdom.”

The first of these philosophers was Emmanuel Levinas, who was preoccupied throughout his life by the ethics of our interpersonal relationships. In his monumentally difficult book Otherwise than Being, Levinas wrote that philosophy was “the wisdom of love at the service of love.” [1]

This claim appears at the end of a particularly knotty passage of philosophy. And it would take us too far off course to plunge into these complexities. But very briefly, what Levinas is suggesting is that the primary impulse towards philosophy—the thing that makes us seek reasons and justifications at all—is our ethical responsibility to others, or love.

The other philosopher who makes the same move is Michel Serres, in his little pamphlet En amour, sommes-nous des bêtes (or In Love, Are We Beasts?). Here, Serres makes an argument from etymology. He says that when we translate the Greek word philosophia, we tend to reverse the two terms, getting them back to front.

The sages define philosophy as the love of wisdom. It must be the case that these learned people are ignorant of language. In most of our composite words, we would do better to read the roots back to front: automobile, that which move itself; geology, science of the earth; tightrope-walker, one who walks on a tightrope… In truth philosophy would then be the wisdom of love. [2]

Serres’s claims about etymology may or may not be correct. But both Serres and Levinas raise interesting questions about how we think about what philosophy is, and what it should aim at. Does being a philosopher mean being somebody committed to wisdom (sagesse, in French) or to becoming sage-like, and thinking better? Or does it mean being somebody who is committed to love (amour), or to loving better? When aiming to become philosophers, are we attempting to become sages or lovers? Or are we to attempting to be both: lovable sages and sagacious lovers?

A tangle of wisdom and love

One suggestion from Ancient Greek philosophy is that perhaps we are aiming at both. In a previous article, we looked at Diotima’s ladder, and the idea of the love as a process of transcendence. In the same passage in the Symposium, Socrates talks about how the philosopher and priestess Diotima taught him that philosophy is a pursuit in which both wisdom and love are tangled up together.

For Diotima, love is interesting because it represents an ambiguous, in-between state. Socrates retells a dialogue with Diotima where he suggests to his teacher that love is a “great god.” But Diotima disagrees. Perplexed, Socrates proposes instead that perhaps love is a mortal being. Again, Diotima says that this is not the case. Instead, she says, love is a “great spirit” that is “between god and mortal” [3].

This is a strange claim, one steeped in mythology. But it is important for how Socrates understands philosophy. Because the love of wisdom also occupies this in-between space, where we are no longer fully in the world of ignorance, but nor are we fully wise. This is the passage from the text.

“In that case, Diotima, who are the people who love wisdom, if they are neither wise nor ignorant?” “That’s obvious,” she said. “A child could tell you. Those who love wisdom fall in between those two extremes. And Love is one of them, because he is in love with what is beautiful, and wisdom is extremely beautiful. It follows that Love must be a lover of wisdom and, as such, is in between being wise and being ignorant.

You could see love as a bridge to wisdom (recalling the bridge of trust in the previous article), one that hovers ambiguously between the states of ignorance and wisdom, without belonging fully to either. For Socrates—and Diotima too—without love to bridge the gap, there is no way that we could challenge our ignorance, and continue our pursuit of wisdom.

Attentiveness: the double paths of love and wisdom

But love and wisdom are not just complementary. They also exist to some extent in tension with each other. They represent two different paths.

There is a long tradition that says the pursuit of wisdom begins in wonder: in a delighted fascination with the world. At the beginning of his Metaphysics, Aristotle writes that:

By nature, all men long to know. An indication is their delight in the senses. For these, quite apart from their utility, are intrinsically delightful, and that through the eyes more than the others. [5]

Philosophy starts with the fact that we like new sensations, and we like the new knowledge these sensations bring. In particular, we like to look at the world, to drink it in with our eyes. This business of delighted, pleasurable looking at the world, Aristotle maintains, is what kick-starts us in the pursuit of wisdom.

But for this sensory delight to be translated into wisdom, for Aristotle we need to be able to see through the multiplicity of the world to the subtle web of underlying principles and causes that binds everything together.

The ideal philosopher, in Aristotle’s view, has a keen eye on two things. First, they are fascinated by the diversity and multiplicity of the world (you could call this love). And second, they are intrigued by the principles that underlie this diversity and multiplicity (you could call this wisdom).

This is why Aristotle himself was interested in pretty much everything, from the nature of the soul to the mating habits of octopuses, from the lives of bees to the most fundamental questions about the nature of space, time, and causation.

The Task of Philosophy: Practices of Love and Wisdom

One way you could see Aristotle’s double-focus is as two different paths of attention. The first path foregrounds wisdom, and seeks out general principles. The other path foregrounds love, and looks for everything that is singular and unique.

This is how the Italian novelist Italo Calvino puts it in his Six Memos for the Next Millennium:

One path, goes into the mental space of bodiless rationality, where one may trace lines that converge, projections, abstract forms, vectors of force. The other path goes through a space crammed with objects and attempts to create a verbal equivalent of that space by filling the page with words, involving a most careful, painstaking effort to adapt what is written to what is not written, to the sum of what is sayable and not sayable. [6]

Perhaps, then, wisdom and love exist in some kind of tension. Wisdom seeks out general principles. Love seeks out uniqueness and singularity. And philosophy sits somewhere in the middle of these things as a practice of deepening both love and wisdom. Then, as we progress on the philosophical path, not only do we understand and appreciate ever more deeply both the general patterns that underlie things, but we are more awakened to the sheer richness and diversity of the world.

Love and wisdom exist in tension, but they also sustain each other. If we only see uniqueness, individuals and singularities, we miss the fabric that knits together the world. But if we only see general principles and patterns, we miss what makes any one thing so singular and unique. And besides, as Diotima knew, it is in the spaces in between—in the tensions, the gaps, the complicated middle places—that the interesting stuff happens.

To finish, then, I want to retell a story about these two paths. In his book Invisible Cities, Italo Calvino tells a parable about Kublai Khan, the ruler of China, and the Italian adventurer Marco Polo.

The two men are playing chess. For the Khan, the chessboard is an abstract representation of his empire. He has reduced the diversity and complexity of the world down to the abstract principles of the chessboard. His moves on the chessboard echo his decisions as emperor. The game of ruling an empire is a vast chess game, a matter of strategy and general principles. But the Khan has been emperor so long, and has won so many victories, he is no longer clear what his empire consists of. Calvino writes,

At checkmate, beneath the foot of the king, knocked aside by the winner’s hand, nothingness remains. By disembodying his conquests to reduce them to the essential, Kublai had arrived at the extreme operation: the definitive conquest, of which the empire’s multiform treasures were only illusory envelopes; it was reduced to a square of planed wood. [7]

You could see the Khan as the representation of somebody who has pushed the path of wisdom to its limit. He has declared checkmate, but is no longer sure what he has won. He has only general principles, but he has lost the uniqueness of the world.

So then Marco Polo leans over the chessboard, and tells the Khan what he sees.

Then Marco Polo spoke: “Your chessboard, sire, is inlaid with two woods: ebony and maple. The square on which your enlightened gaze is fixed was cut from the ring of trunk that grew in year of drought: you see how its fibers are arranged? Here barely hinted knot can be made out: a bud tried to burgeon on a premature spring day, but the night’s frost forced it to desist…” [8]

Marco goes on talking, moving backwards from general principles to specifics, and suddenly the empire comes flooding back in, and the Khan once again understands what it means not just to rule the empire, but perhaps also to love it. Calvino ends the passage like this:

The quantity of things that could he read in a little piece of smooth and empty wood overwhelmed Kublai; Polo was already talking about ebony forests, about rafts laden with logs that come down the rivers, of docks, of women at the windows…[9]

Calvino’s vision of life is one where wisdom and love support each other, even while they exist in tension with each other. If there is always this tension between love and wisdom, we can perhaps never find true wisdom (and perhaps we shouldn’t aim to). Likewise, we may never find true love. But in the back-and-forth between the two, we can find deeper ways of appreciating and understanding the world: both the general patterns that underlie all things, and the uniqueness of every single thing and every single situation.

Questions

Here are some questions to get you thinking about this week’s article. If you are a member, dive into the comments on the Agora, and let’s chat.

- The claim I am making here is that love is about understanding specifics and what makes something unique, and wisdom is about understanding general principles. But is this true?

- If you think of philosophy as the “wisdom of love”, how does this change your idea of what philosophy is, and what it should do?

- Is true wisdom possible? And what about true love? Does one exclude the other?

- In what sense is love something that exists “in between” (you might want to have a look at the Philosopher File on Diotima here).

- We often think that tension between different approaches to life is something to be eradicated or overcome. In this piece, I’m suggesting that these tensions can be creative, even if you can’t overcome them. Is this really the case?

- Finally, looking back on the whole course, how—if at all—has your understanding of love shifted since you started the course?

Notes

[1] Emmanuel Levinas, Otherwise than Being, Or Beyond Essence (Duquesne University Press), p. 162

[2] Michel Serres, En amour, sommes-nous des bêtes (Le Pommier, 2002)

[3] Symposium 202e. See John M. Cooper (editor), Plato: Complete Works (Hackett 1997), p. 485.

[4]Symposium 204b. See John M. Cooper (editor), Plato: Complete Works (Hackett 1997), p. 487.

[5] Aristotle: Metaphysics, translated by Hugh Lawson-Tancred (Penguin Books 1998), [980a], p. 30.

[6] Italo Calvino, Six Memos for the Next Millennium (Penguin Modern Classics 2009), p. 74

[7] Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities (Harcourt Brace 1974), pp.131-2

[8] ibid.

[9] ibid.

More further reading

This week’s song is Cher’s Love and Understanding. Listen to it on YouTube.

There’s a nice, short piece on Invisible Cities on the NPR blog. See the link here.

Thinking about the tension between Marco Polo and the Khan, and between love and wisdom, it might be fun to explore the ancient Greek philosopher Empedocles, who saw the universe as a tension between love and strife.

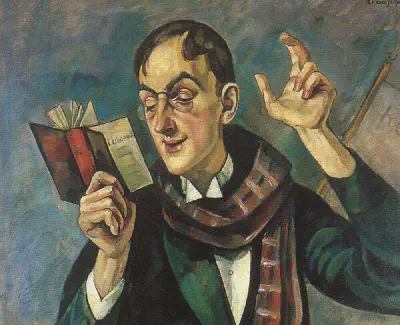

Image: Saint Sophia, patron saint of wisdom, with her daughters Faith, Hope, and Love. By F. Huberti (17th Century). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.