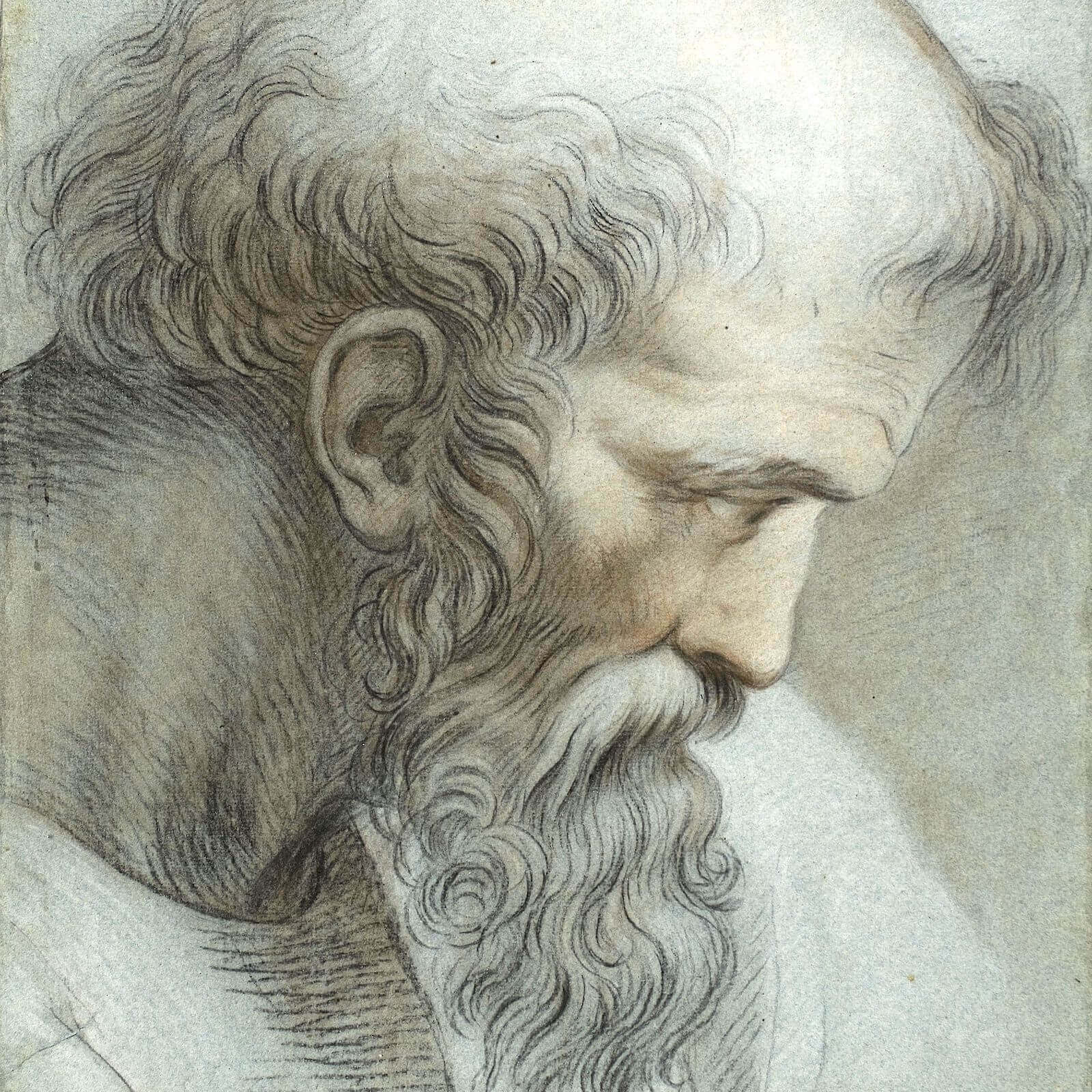

Life

Pythagoras was born some time after 570 BCE on the island of Samos. Some accounts say he travelled widely during his early life, as far as Egypt, Babylonia and Persia, and this may have had an influence on his philosophical development. Other stories say that he visited both Thales and Anaximander in Miletus whilst in his twenties. All these stories may be true, but we know little about his early life for certain.

What we do know is that around 530 BCE, he travelled to Kroton, a Greek city that is in present-day Italy; and there he settled and founded his own philosophical school. Pythagoras quickly gained a large following in Kroton, and became a significant influence on the life of the city.

Secrecy and silence

The Pythagorean school functioned like a religious community, bound by strict rules and by secrecy. Entry into the Pythagorean community was arduous, and may have involved undertaking a five-year vow of silence, where new initiates listened to the teachings, but were not permitted to speak.

One result of this secrecy is that it is hard to say precisely what it was the early Pythagoreans taught. They were probably largely vegetarian, and lived in a state of communal austerity. Other less than reliable accounts say that Pythagoras also shunned eating beans because — beans being soft and somewhat fleshy — Pythagoras argued they had souls.

One thing that made the early Pythagoreans particularly radical was the inclusion of women in the philosophical community. The early records of the Pythagoreans contain multiple accounts of women philosophers, with seventeen women philosophers mentioned by name, including Theano of Kroton, who may have been Pythagoras’s wife, and who was a prolific writer, even though little of her writing remains.

Pythagoreans in power

For all its secrecy, the Pythagorean community grew quickly, and it became important to the political life of Kroton. Many members of the Pythagorean community rose to positions of political power across southern Italy. And the Pythagoreans have been credited with playing a role in Kroton’s military victory over the neighbouring city-state of Sybaris, their discipline and focus helping the state of Kroton overcome the famously lax Sybarites.

But political power always comes with a cost. And as the Pythagoreans gained in power, they attracted enemies. Later accounts talk about uprisings against Pythagorean communities. It is said that Pythagoras himself fled Kroton, and went into exile in the city of Metapontum, in the very south of present-day Italy.

According to some accounts, this is where he died. His enemies tracked him to Metapontum, and then they pursued him to the edges of a bean-field. Not wanting to trample on the beans, and to destroy so many souls, Pythagoras chose death instead. This story, although colourful, is not entirely plausible.

Philosophy

Pythagoras was the first philosopher to talk about philosophia (φιλοσοφία) or ’the love of wisdom.’ The idea of loving wisdom puts a distance between ourselves and wisdom: if we love wisdom, it is precisely because we are not wise (see also the Philosopher File on Diotima). Two ideas in particular are associated with the Pythagorean pursuit of wisdom: the idea of the transmigration of souls; and the idea that numbers are somehow fundamental to reality.

Travelling souls

One of Pythagoras’s distinctive teachings was the transmigration of the soul. In other words, the soul is something that exists beyond death, and that can be reborn in other bodies: whether human or animal. There is a famous story told by Diogenes Laërtius about Pythagoras and a dog. One day, the philosopher came across somebody beating a puppy. Pythagoras intervened and told the man to stop. He said that in the puppy’s squeals he recognised the voice of one of his deceased friends.

Later Greek thinkers traced this idea of the transmigration of the soul back to Egypt; and it may provide some evidence of Pythagoras’s youthful travel. It is an idea that appears again in the work of Plato, although he doesn’t cite Pythagoras as a source. And although the idea of the soul’s transmigration didn’t take hold after Pythagoras and Plato, it may have influenced the Western philosophical traditions in more subtle ways. Because if the soul can move from body to body — as both Pythagoras and Plato argued — this means that body and soul are, in principle, separable. And this idea of the separability of the body and the soul has endured for centuries in the traditions of philosophy that trace their origins back to Ancient Greece.

Numbers

Numbers were central to Pythagorean philosophy. Today Pythagoras is still chiefly famous for his theorem: the square of the hypotenuse of a triangle is equal to the sum of the squares on the other two sides. More recent evidence suggests that this was already well-known in both India and Babylonia, and that the idea predates Pythagoras by up to 1000 years. So Pythagoras cannot be credited with its discovery; but he or his followers may have been responsible for introducing it to the Greek world.

The Pythagoreans were also associated with the idea that the universe as a whole is underpinned by numbers. Aristotle, no fan Pythagoras, wrote that:

For them [the Pythagoreans] the entire universe is constructed from numbers — Aristotle, Metaphysics

But the actual view of Pythagoras may have been more subtle. One fragment attributed to Theano says that:

I have learned that many Greeks think Pythagoras said everything is created from number. This statement itself raises a question. How can what does not exist think and reproduce? But he did not say everything is derived from number, but everything is generated according to number, that the primary order is in number.

If this passage is authentic, it suggests that Aristotle got Pythagoras wrong. It is not that, as Aristotle claims, everything is made up of numbers. Theano recognises that in themselves numbers can’t reproduce or create anything. Instead, she argues that there is a mathematical regularity underpinning the world.

This is an idea that has remained immensely powerful throughout the two and a half thousand years since Pythagoras’s time.

Further Reading

Books

If you are interested in the role of women in early Pythagorean communities, then I highly recommend Sarah B. Pomeroy’s Pythagorean Women: Their History and Writings (Johns Hopkins University Press 2013). The quote from Theano comes from this book (p. 67).

One of the best surveys of Pythagoras and his school is Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans: A Brief History by Charles H. Kahn (Hackett 2001).

Online Resources

Here’s some fun background from Atlas Obscura on the role of beans in the ancient world.