Zeno of Elea is one of those shadowy ancient philosophers about whom we know very little. According to some accounts, he was the student of both Parmenides and Xenophanes.

Zeno appears in Plato’s Parmenides, where he is visiting Athens together with his teacher. There, the two philosophers meet the young Socrates, upon whom Zeno makes a substantial impression. If Plato’s story is true, this would mean that Zeno was born some time around 490 BCE.

This is how Plato tells the story:

Parmenides was already quite venerable, very gray but of distinguished appearance, about sixty-five years old. Zeno was at that time close to forty, a tall, handsome man who had been, as rumor had it, the object of Parmenides’ affections when he was a boy. Antiphon said that the two of them were staying with Pythodorus, outside the city wall in the Potters’ Quarter, and that Socrates had come there, along with a number of others, because they were eager to hear Zeno read his book, which he and Parmenides had just brought to Athens for the first time. Socrates was then quite young. [1]

Zeno may have influenced Socrates’s approach to philosophical argument. Aristotle later claimed that Zeno invented dialectic—reasoning based on argument and counter-argument. And this process of argument through dialectic was a cornerstone of the method of philosophical questioning developed by Socrates.

Troubles with tyrants

We don’t know much about Zeno’s life. But as usual, where the historical record fails us, the biographer Diogenes Laërtius steps and fills the void with entertaining stories that may or may not contain a grain of truth.

According to Diogenes’s Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, Zeno attempted to overthrow the tyrant Nearchus (or in some accounts, the tyrant Diomedon). He failed and was arrested. Under torture, Zeno refused to reveal his accomplices, but did manage to bite off the tyrant’s ear before he was run through with a sword.

There are good reasons to be sceptical of this story, not least because it exists in several variants, with different tyrants and different chewed-off body parts. In an alternative account, Zeno bit the tyrant’s nose. And in yet another, the tyrant was called Demlyus, and instead of biting off part of the tyrant, Zeno bit off his own tongue and spat it in the tyrant’s face.

Philosophy

Zeno is most famous for his paradoxes. And these paradoxes still have the power to mess with our everyday assumptions about the things like space, time and motion.

Sometimes Zeno’s paradoxes are presented as mind-bending puzzles or diversions. But there is serious philosophical intent here. And if we are to understand the rationale behind these paradoxes—and to understand why for Zeno they were more than simple intellectual puzzles—we have to put them in the context of a strange idea proposed by his teacher Parmenides: the idea that nothing ever changes.

The illusion of change

Parmenides questioned two everyday assumptions we make about the world. The first assumption is that things are plural—that there are many things in the world. And the second assumption is that things are constantly changing.

Both of these seem quite reasonable claims. Obviously, there are lots of different things in the world. And obviously, these things undergo change. But Parmenides disagreed. However things may appear to be, Parmenides argued, the reality is this: all of being is made up of one single thing; and this single thing never changes, ever.

As we saw in an earlier Philosopher File, according to Parmenides, being as a whole is:

ungenerated and indestructible, whole, of one kind and unwavering, and complete. Nor was it, nor will it be, since now it is, all together, one, continuous. [2]

Things may seem to change, Parmenides insists, but in reality, they don’t (incidentally, Parmenides knows this, because it was a truth revealed to him by a goddess—so how could it not be true?).

However, this leaves us with a problem. If things only seem to change, but in reality don’t, how do we account for this seeming? Zeno’s paradoxes don’t answer this question directly. But they do offer a challenge our everyday perceptions and assumptions. And for Zeno, this undermines our confidence in how things seem to be, giving more weight to the thought that Parmenides might—_just migh_t—be right.

Achilles and the tortoise

Here we’ll take just one of Zeno’s paradoxes, the famous paradox of Achilles and the tortoise.

Zeno asks us to imagine that Achilles, the Greek hero, is in a race with a tortoise. Achilles is a good sport, and is confident in his own prowess, so he gives the tortoise a little bit of a head start. Then the race begins. Any sensible person betting on the race would put their money on Achilles. Even with that famous heel of his, it’s pretty obvious that the athletically inclined hero can outrun a tortoise.

Or can he? Because Zeno believes he has a knock-down argument to demonstrate that, despite our everyday intuitions, Achilles can never catch up.

How can this be?

Imagine that the tortoise starts out at point A. By the time Achilles has reached point A, the tortoise will be a little further ahead at point B. So Achilles continues running, but by the time he has reached point B, the tortoise—bravely striding into the distance—will be at point C. And this process can be repeated to infinity, with Achilles always lagging behind the stolid little tortoise.

In the Physics, Aristotle sets out the argument like this:

The slowest runner in a race will never be overtaken by the fastest. For the pursuer must first reach the point from which the former started, so that the slower must always be a bit ahead. [3]

For Zeno, faithful to his teacher Parmenides, this paradox provides support to the idea that everyday appearances are a poor guide to how things actually are, and to the counterintuitive conclusion that motion is simply an illusion.

Outrunning Zeno

Zeno’s paradox is surprisingly hard to think about, and even harder to crack. Since Ancient Greek times, many thinkers have proposed solutions to the paradox. Others, irritated by its intractability, have tried to dismiss it entirely, saying that Zeno is only playing with words.

But after two and a half thousand years, the paradox still seems to be frustratingly elusive. Every time you think you’ve caught up with what is going on and got hold of an answer, the paradox ambles onwards, just a bit further out of reach, like that damned tortoise.

Is Zeno’s paradox telling us something about the nature of reality? Or is it, as some argue, telling us something about how our intuitions about space, time and motion are wrong?

I’m not going to attempt to set out a solution here: that would involve plunging down rabbit-holes of philosophy, physics and mathematics. So I’m going to leave for you to think about yourself, because it can be fun to try and outrun Zeno. And if you are struggling to catch up, have a look at the links below for some possible solutions.

Notes

[1] Parmenides 127b. In John M. Cooper (editor), Plato: Complete Works (Hackett 1997), p. 361.

[2] Quoted in Jonathan Barnes, Early Greek Philosophy (Penguin 1987), p. 134.

[3] Aristotle, translated C.D.C. Reeve, Physics (Hackett 2018), VI 9, p. 92.

Further Reading

Books and articles

Try Joseph Mazur’s Zeno’s Paradox: Unravelling the Ancient Mystery Behind the Science of Space and Time (Plume 2008).

Online Resources

Here are the various accounts of Zeno’s death, with the original Greek texts.

Here’s one set of approaches to Zeno’s Achilles paradox.

And here’s another discussion of how to solve this knotty, frustrating problem.

And finally, another stab at it from Quartz.

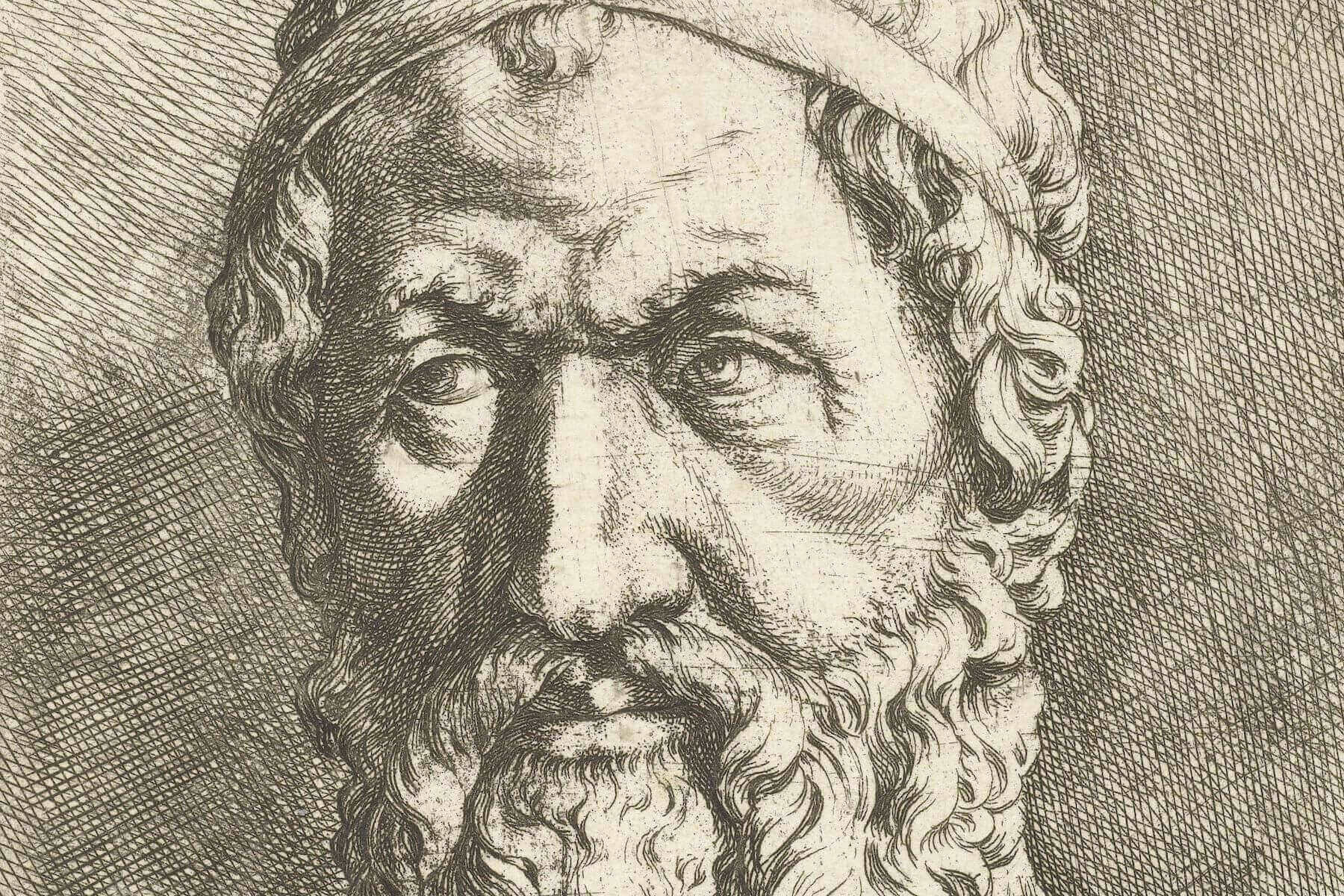

Image: 17th century etching of a bust of Zeno of Elea. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.