Over the last four articles in this series, we have been exploring divergent ideas of work. What is work? What role does it play in human life? How can we think better about work? Is work our salvation or our ruin? Is it the path that leads to virtue, or does it lead to our own destruction?

But when you start to think about work, you are also—by implication at least—thinking about non-work. These ideas of non-work form the backdrop for our thoughts about work. So in the next two pieces, we’re going to look more deeply at two kinds of non-work: idleness and play. And we’ll start with idleness.

Kurt Vonnegut once wrote, “I tell you, we are here on Earth to fart around, and don’t let anybody tell you different.” For many thinkers, this kind of “farting around” (or idleness) is a vice in need of correction. Benedict of Nursia, who wrote the book on monasticism, argued that idleness opens the door towards sin, and is ruinous of our virtue. John Locke (1632-1704) argued that even in our leisure time, we should bury ourselves in useful pursuits because uselessness causes anxiety and makes us unhappy. And Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) argued work is a purifying fire that frees us from all ills.

But should we dismiss idleness quite so easily? Or do we need to take it more seriously as a central component of human life?

Work, Idleness, and Rest

Within cultures preoccupied by the idea that work is inherently valuable—for example the culture of Benedict’s monastery—there is often a clear line between idleness and rest. Rest is non-working for the sake of work. You have had a busy week, so you take a weekend to rest and recharge your batteries. Then you can return to work with renewed vigour. In his monastic rule, Benedict accepted the need for rest because rest is a necessary part of a life structured in accordance with work. We are not automata. We do not have infinite resources available to us. Rest is a way of maintaining our vigour and focus in a life built around work.

If rest is necessary to support work, idleness is—as Benedict knew—a far more subversive, or even corrosive, idea. Idleness is non-working, but not for the sake of work. Instead, idleness is non-working for its own sake. It is a kind of non-working that refuses to frame our understanding of what makes human life good or meaningful in terms of the work we do.

This is why the idea of idleness can be so very challenging. Work is often the framing narrative we use so we can understand our lives and the value of our lives (“What do you do?” we ask a new acquaintance). From the point of view of this framing narrative, the measure of a person is not how much fun they have, or whether they enjoy lying on their backs in the sun, or whether they are good to hang out with. Instead, it is the work that they do.

But when we start to take idleness seriously, we can step outside this frame, and think about human life differently.

Beyond productivity

The way we think about work and idleness says a lot about our notion of what a life ideally lived might look like, or what human flourishing might look like.

Within work cultures, we often hunger to become more successful, more efficient, more productive, more creative. And we take this continual enhancement to be a vision of human flourishing. But this is not the only possible vision of human flourishing, and it is a vision that can come at a cost: burn-out, anxiety, the nagging fear that the things that we are so frenetically producing may be of little worth, and so on. It also comes at the risk of failure: in a world defined by success, not everyone can be successful. And falling short of the demands that we should succeed can be a severe blow to our self-esteem.

But perhaps there are different ways of framing human life. What if we realigned our values so that we didn’t see work and productivity as the centre-pieces of a life well lived? What if, instead of ceaselessly doing stuff, we tried to cultivate doing nothing, at least once in a while? As Jenny Odell writes in her recent book How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy, in a world obsessed by productivity, idleness might be an act of political resistance.

I consider “doing nothing” both as a kind of deprogramming device and as sustenance for those feeling too disassembled to act meaningfully. On this level, the practice of doing nothing has several tools to offer us when it comes to resisting the attention economy. [1]

Rethinking non-work

One of the philosophical texts that most directly challenges our ideas about work and non-work is the Chinese Daoist text known as the Zhuangzi. Although the many stories in the Zhuangzi recognise the value of craft, skill and work, it is also a book that sings the praises of farting around, and directly questions the idea that we should cultivate usefulness as a means of validating our existence.

An image that crops up again and again in the Zhuangzi is that of a tree so old and gnarly, so twisted out of shape, that it is of no use to anybody. In one passage, a carpenter called Shi and his apprentice stand admiring an old tree. Shi says,

This is worthless lumber! As a ship it would soon sink, as a coffin it would soon rot, as a tool it would soon break, as a door it would leak sap, as a pillar it would bring infestation. This is a talentless, worthless tree. It is precisely because it is so useless that it has lived so long. [2]

And for the Zhuangzi, there is something exemplary in a gnarly old tree like this. Trying to be useful risks harming our nature. But being useless is a way of guaranteeing our longer-term well-being. Later on in the text, the argument is summarised like this:

The mountain tree plunders itself. The candle fat scorches itself. The cinnamon tree is edible, and thus it gets chopped down. The lacquer tree is useful, and thus it is cut down. Everyone knows how useful usefulness is, but no one seems to know how useful uselessness is. [3]

Being useless, the Zhuangzi suggests, unhitches our life from the instrumental demands of those who might seek to control us, who might seek to use us as raw material in their schemes, to chop us up and turn us into useful things. Usefulness puts us in danger. If we really want to live out our span of years, our best bet, the Zhuangzi suggests, is to make ourselves as useless as possible.

Defining idleness

The Zhuangzi challenges us to rethink our assumptions about whether useful activity can really be the hallmark of a life well-lived. Perhaps we need to give idleness more of a hearing.

In his fascinating recent philosophy of idleness, Brian O’Connor sets out to do just this. In his book, O’Connor does not necessarily advocate for idleness. Instead, what he is suggesting is more subtle and more far-reaching. He is suggesting that if we take the challenge of idleness seriously, it forces us to rethink all the parameters in terms of which we judge life to be good or well-lived, and to ask some deep questions about the meaning of human freedom.

O’Connor sets out some characteristics of idleness. Idleness, he says, involves “noncompulsion and drift.” The author of the Zhuangzi, called this noncompulsion xiao yao you or “free and easy wandering.” When you are wandering freely and easily, you are not goal-oriented: you are not aiming at anything. You are drifting, and enjoying the deliciousness of being without purposes and goals.

This leads us to another characteristic of idleness: it isn’t aimed at productivity. Thoughts may come to us in idleness, or they may not. But if they come at all, they come serendipitously. And not just thoughts. If we are sitting on the porch with a block of wood and a knife, if we have sufficient idleness, we may find ourselves whittling a spoon out of the wood (to take the classic example). But our whittling is not purposive, and the spoon just emerges from the wood serendipitously.

A further characteristic, O’Connor argues, is that idleness does not involve discipline and self-monitoring. It doesn’t aim at self-realization or self-betterment. The idle self couldn’t care less about these things. It is, O’Connor argues, at home with itself. It doesn’t see happiness as an achievement or a reward, but is just happy to be the kind of being that it is.

Despite all this, O’Connor says, idleness is not mindless. It knows what it is doing and knows what it is about, even if it has no particular end or purpose.

O’Connor concludes by saying,

[Idleness] does, after all, seem to place us in a liberating possession of ourselves, free of pressure, and evidently content. From these characteristics it is obvious that idleness stands in opposition to much of what is taken to be right and normal: it has nothing to do with performance, with work, with social standing, with gaining in prestige. [4]

The freedom of doing nothing

In a culture obsessed by work and productivity, and the prestige of work and productivity, we often think of freedom as something that is won through our work. So if you work for a sufficient number of years, you are considered to have earned your retirement. And once you are retired, it is okay to be idle—but only because through work you have earned the right to be idle. Non-work is an achievement, one that you can only reach (if you care about virtue) by means of work.

But both the Zhuangzi and O’Connor suggest a more radical vision of freedom. What if the opportunities for freedom were there all along, and to attain to this freedom what we need to do is not to work for our freedom, but instead to give up on our obsession with work?

This is why—for Jenny Odell, for the Zhuangzi and for Brian O’Connor—a reappraisal of idleness offers us something radically transformative. O’Connor writes,

The case for idleness […] will depend on whether questions of freedom can be asked without framing the answers within notions of the type of people required by modern societies. The implications of such a shift are not insignificant. They point to the implausible-sounding scenario in which the phenomena of usefulness, competitive social identities, or long-term discipline no longer form the outlines of our experience. A reappraisal of idleness is, in this respect, also criticism of those notions of freedom that work in favor of life determined in those ways. [5]

Idleness for all!

However, there are important questions of social justice here. Remember that Aristotle himself believed work-free leisure to be the best and most noble form of human life, but he also recognised that this kind of existence was only possible on the understanding that certain groups of people—slaves, servants, women—provided the labour that enabled this leisure to exist.

But not all idleness is the same. Blanket approval of idleness, or blanket condemnation, misses much of what is interesting about idleness as a component of human life. In exactly the same way, blanket approval of work, or blanket condemnation, misses much of what is interesting about work as a component of human life. Cultures of work can be conducive to building a more just and equal society, or can serve to further entrench injustice and inequality. And it is the same with cultures of idleness.

In her brief history of European ideas of idleness, Ingrid Nelson draws a distinction between simple slothfulness (the kind of personal idleness that the Romans called accidia) and civic-minded leisure (which the Romans called otium). __ Nelson argues that instead of simply arguing for or against idleness, we should instead develop a more subtle ethics of idleness. Because if we play it right, thinking better about idleness might be one way that we resist the demands upon us. And this might help us to restructure our societies, to make them more equitable and more conducive to flourishing for all.

So, should you be more idle? The answer, Nelson suggests, is complicated. It depends on how you play it.

Personal idleness restores and renews but can also lead to antisocial or exploitative behavior. Civic-minded idleness acknowledges our connection with society even as we withdraw from it, giving us space to explore, play and discover. Ultimately, this should lead to a more equitable society. [6]

This question of exploration, play and discovery is something we’ll pick up again in the next piece when we look at another aspect of non-work, and explore the philosophy of play.

Questions

- In what ways is uselessness useful?

- Can idleness really be an effective form of political resistance as Jenny Odell suggests?

- When have you felt most truly free? When you are working? When you are idle? Or some combination of the two?

- What is your own experience of idleness? Does it make you anxious (like John Locke)? Or do you enjoy the “free and easy wandering” that comes from being idle?

- Is there something inherently unjust or inequitable about the idea of idleness? Or can idleness support a more just and equitable society?

Notes

- Jenny Odell How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy (Melville House 2019), eBook.

- Brook Ziporyn (translator), Zhuangzi: The Essential Writings (Hackett 2009), eBook.

- Ibid.

- Brian O’Connor, Idleness (Princeton University Press 2018), eBook.

- Ibid.

- Ingrid Nelson, “‘Doing nothing’ is all the rage — is it a form of resistance, or just an indulgence for the lucky few?”, The Conversation (March 2021). Read it here.

More further reading

Books and articles

One of the most famous of all 20th century philosophical texts on idleness is Bertrand Russell’s In Praise of Idleness. There’s an edition published by Routledge in 2004 (In Praise of Idleness: And Other Essays), but you can also find the essay easily online.

Online resources

See this piece from Philosophy Now on Locke and the idea that idleness makes us anxious.

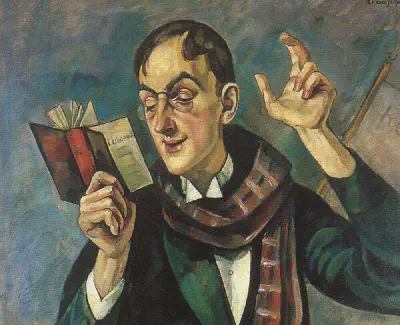

Image: Idle Hours by Henry Siddons Mowbray (1895). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.