In last week’s piece, we explored how work might of benefit to us—how it might even be our salvation. For some thinkers, work is inherently ennobling and self-improving. It is, as Carlyle put it, a “purifying fire, wherein all poison is burnt up.”

Even if we don’t go as far as Carlyle, we have already seen that work can be beneficial in that it provides us with a range of both internal and external goods. Work gives us a social context. If it is the right kind of work, it makes use of our skills in a satisfying way. It develops those skills further (and developing skills is fun). It can be stimulating and enjoyable. And it enables us to provide for ourselves and those close to us.

These are all good things. So there’s no wonder that research shows that work can be an important factor contributing to the sense we might have that our lives are going well for us—what has come to be known as our “subjective well-being.” And any account of work (for example, Aristotle’s) that ignores these positive aspects, and that doesn’t pay any attention to the internal and external goods that work provides is going to fall short.

Nevertheless, work is often burdensome, hard or even soul-destroying. When we talk about work, we sometimes do so with excitement and enthusiasm, but equally frequently we do so with a sense of frustration or heaviness. Work gets us down.

Why is this the case, given all the research that shows how work is good for us? Is there something wrong with us? Are we just being perverse when we complain about work? Or is there a darker side to work?

The darker side of work

One recent thinker, the anthropologist David Graeber, believes there is. In his essay—and later his book—on the phenomenon of what he calls “bullshit jobs”, Graeber talks about the “moral and spiritual damage” of our modern work-cultures. Our modern-day attitudes to work, Graeber writes, constitute a “scar across our collective soul.”

In this piece, we’re going to look at three ways in which our cultures of work may be the cause of a kind of moral or spiritual damage: the first is unemployment, the second is overwork, and the third is Graeber’s phenomenon of “bullshit jobs.”

But first, I want to say something about the term “spiritual.” When talking about the spiritual damage caused by work, I don’t mean anything mystical or religious (and neither does Graeber). Instead, I am using the term “spiritual” to capture the all-pervading effect our attitudes to work have on our existence. When work gets us down, we feel dispirited. It feels as if something has left us: a sense of liveliness, hope, creativity, excitement. “Spiritual” harm, in this sense, refers to the way that work can make our lives less spirited, less lively, less full and rich and meaningful.

On the spiritual harms of unemployment

It is often argued that work is good for us because unemployment is so clearly bad for us. In his book on the philosophy of work, Lars Svendsen cites A. Kim Burton and Gordon Waddell’s report Is Work Good for Your Health and Well-Being? This report, commissioned by the British government and published in 2006, seems to provide robust support for the idea that working is good for us, and that unemployment is correspondingly bad for us. Svendsen summarises Burton and Waddell’s findings as follows,

In terms of a negative effect on happiness, or “subjective well-being” as it is often called in empirical studies, unemployment is one of the things with the highest impact, along with serious illness and divorce. It seems that loss of income is only a minor part of this and that other factors have greater impact than the purely economic ones. The “typical” unemployed will have less social interaction with others and lower self-esteem. People take unemployment personally. [1]

Unemployment deprives us of income, of status and of social interaction. No wonder it is so destructive. The authors of the report conclude that,

There is a strong evidence base showing that work is generally good for physical and mental health and well-being. Worklessness is associated with poorer physical and mental health and well-being. Work can be therapeutic and can reverse the adverse health effects of unemployment. [2]

This suggests that Benedict of Nursia was onto something when—as we saw last time—he counselled that in the monastery, “Brothers who are sick or weak should be given a type of work or craft that will keep them busy without overwhelming them or driving them away.” [3] And Burton and Waddell’s report seems to provide pretty compelling evidence that we’re better off working than not working.

However, we need to look at this more closely, because this litany of the harms of unemployment is a less compelling argument for the goodness of work than it first seems.

One obvious benefit of work is that it provides us with income. Burton and Waddell write that for those who are unemployed,

Re-entering work (rather than simply moving off benefits) is generally associated with improvement in income, socio-economic status, mental and general health, and well-being. [4]

This is not surprising. Having insufficient income to support ourselves and those who depend upon us is a genuine harm. But the absence of income is not inherent to being outside of a waged job. It is possible to envisage alternative social systems—ones with substantial unemployment benefits, or where there is some kind of universal basic income—that might mitigate these harms of being out of work. The issue here is not the absence of work itself, but the absence of sufficient income to live a life where one can meet one’s needs.

Another benefit of work is that it gives us a concrete social (or socio-economic) status. We are social primates, and status matters to us. But here again, we need to look more closely. The reason that being outside of waged work entails an absence of status is that we live in a culture where one of the major determinants of status is what waged work we do. If unemployment is seen as being low-status—or even blameable—this is because we live in a culture that places a huge moral value on waged work. The loss of status that goes with unemployment is not due to the absence of work. It is due to a culture that sees work as the highest good, and unemployment as a state that is morally reprehensible.

Burton and Waddell’s conclusions are not without nuance. They caution that work is only better than unemployment if you have what they call a “good job”— a job that supports our health and well-being, and that gives us sufficient autonomy to feel that we are active agents in the world.

But it’s possible to turn this round, and to ask if there are “good “and “bad” jobs, why there shouldn’t be “good” and “bad” forms of unemployment as well. In other words, the reason that unemployment is bad for us is that we are committed to sustaining a system of bad unemployment, a system in which unemployment necessarily compromises health, well-being, and autonomy. Arguably, a more humane political and social system would ask not just how to make work good, but also unemployment. It would be a system that saw some degree of support for our health, well-being and autonomy not as things that we achieve when we enter the world of work, but as the non-negotiable ground of our existence as citizens.

On the spiritual harms of overwork

Nevertheless, Burton and Waddell’s caution about “good jobs” is important. Because while we can find meaning and purpose in work, not all jobs will enable us to do this. And this leads us to another potential spiritual harm caused by work: the harm of simply working too hard. In a culture that is driven by an overarching work ethic, a culture that sees work as a path to virtue, it is easy to see how overwork can become a problem. The harder we work, the more virtuous we feel ourselves to be. We are encouraged to compete with each other for the status that comes from being the most virtuous and the most hard-working. And in cultures such as this, being worn out and ragged is seen as a badge of virtue.

This, of course, comes at significant cost. But it is not inevitable that we view work like this. We’ve already seen one philosopher—Aristotle—who is sceptical about the value of work, and who sees work as something that is “unchoiceworthy” and that we should limit as far as possible. Meanwhile, over in China, the *Zhuangzi—*a text attributed to the 4th century BCE philosopher Zhuang Zhou—offers a fascinating insight into how we might work differently.

The Zhuangzi is sometimes represented as a kind of slacker text that encourages us to bunk off work as much as we possibly can. But it is more interesting than that. What the Zhuangzi encourages us to do is to think about what it means to work in a way that nourishes our life (the Chinese term for this is yang sheng). To nourish our life is to guard our energy and our vitality, whatever activity we are engaged in. This idea of life as something to be nourished is associated with the famous idea of wu-wei, which is sometimes translated as “non-doing”, but which could be better understood as optimally minimising our activity. The idea of wu-wei is that we should do as little as we can to accomplish what we want to accomplish, and no more. Because anything beyond this risks sapping our spirits and exhausting us. In his brilliant book, Trying Not to Try, Edward Slingerland writes,

Wu-wei is characterized by an internal sense of effortlessness and unselfconsciousness, even though the person in wu-wei may actually be very active in the world. [5]

The Zhuangzi often presents wu-wei as a personal achievement. But if we care about the spiritual harms of work, perhaps we need to think about how our cultures of work wear us out and exhaust us, and put in place new approaches to work that are rooted in the idea of optimally minimising our effort, so that we can nourish our lives.

On the spiritual harms of bullshit

The final spiritual harm of work that I want to consider here is the spiritual harm of what Graeber calls “bullshit jobs.” A bullshit job is a job which simply doesn’t need to exist, a job that, while you are doing it, you know is fruitless, pointless or without any value. Graeber defines it like this:

a bullshit job is a form of employment that is so completely pointless, unnecessary, or pernicious that even the employee cannot justify its existence. [6]

What is crucial to Graeber’s definition is that the employee themselves has this nagging suspicion—or this clear apprehension—that their job has no actual value. Bullshit jobs are particularly weird because although they may be lucrative, and they may even entail nothing objectively unpleasant (you may have a good salary, be in a warm office, have plenty of time on your hands, and nobody bothering you), they are still strangely harmful. Their sheer pointlessness—the knowledge that if this job disappeared entirely, the world would be more or less unchanged—is somehow spiritually corrosive.

Even many jobs that seem objectively useful may seem to involve large amounts of bullshit: in other words, innumerable tasks that serve no obvious purpose, that are there simply to keep us busy, or to make people look good, or to fulfil meaningless criteria. And this bullshit is destructive of our well-being. Graeber writes that,

Bullshit jobs regularly induce feelings of hopelessness, depression, and self-loathing. They are forms of spiritual violence directed at the essence of what it means to be a human being. [7]

Why is this? Graeber argues that it is because we need the sense that we are having an appreciable effect on the world. For our life to be spiritually rich and meaningful, we need to feel that we are being a cause in the world. When this is not the case, we lose our moorings.

Undoing spiritual damage

So here are three ways in which our culture of work can cause spiritual damage. It can harm us by setting up a system where non-work is equated with the misery and lack of agency that comes from unemployment. It can harm us by simply wearing us out, so we can’t do anything else. And it can harm us by making us engage in tasks that have no benefit, so eroding our sense of ourselves as beings who can have an effect on the world.

All three forms of spiritual harm share one characteristic: they undermine our ability to act in the world on the basis of our own creative agency. When we are unemployed, when we are overworked, or when we are forced to engage in a pantomime of useful work knowing all the time that our work is useless, what we have lost is the sense of ourselves as agents in the world, capable of creating something new.

If this diagnosis is correct, then it becomes possible to see the outlines of a more humane attitude to work. Perhaps the question we should be asking is not whether work is in itself good (like Carlyle) or bad (like Aristotle). Instead, we should be asking how we can transform our cultures of both work and non-work, so that we build a society that leaves room for agency and creativity for all of us.

To do this, we also need to think harder not just about work, but also non-work. So this is what we’ll be doing in the next two articles, where we’ll ask some deeper questions about two varieties of non-work: play, and idleness.

Questions

- If unemployment is a spiritual harm (in the sense set out above), is this essential to the state of being unemployed? Or is it a result of our cultures of work? Why do you think this?

- I have suggested that the idea of wu-wei is that we should do “as little as we can to accomplish what we want to accomplish.” How might this be a good thing? And how might it be a bad thing?

- Do you have any experience of wu-wei in your own life?

- Have you ever been in (or are you in) a bullshit job? If not, what percentage of your current job (if you have one) would you say is bullshit?

Notes

- Lars Svendsen, Work (Routledge 2016), p. 71

- Burton and Waddell, Is Work Good for Your Health and Well-Being (The Sationery Office 2006), p. ix

- Timothy Fry, translator, The Rule of St. Benedict in English (The Liturgical Press 1983), p. 70

- Is Work Good for Your Health and Well-Being, p. 34

- Edward Slingerland, Trying Not to Try (Crown Publishers 2014), p. 19

- David Graeber, Bullshit Jobs (Simon & Schuster 2018), p. 14

- ibid. p. 80.

Further Reading

Books and other things

The report by Burton and Waddell is available for free from TSO. You can read the full report here.

I’ve taken the idea of optimal minimisation from An Introduction to Daoist Philosophies by Steven Coutinho (Columbia University Press 2013).

Online Resources

If you haven’t already, you should listen to the Old Lady Job Justification Hearings from Mitchell and Webb.

This piece on happiness at work is well worth reading.

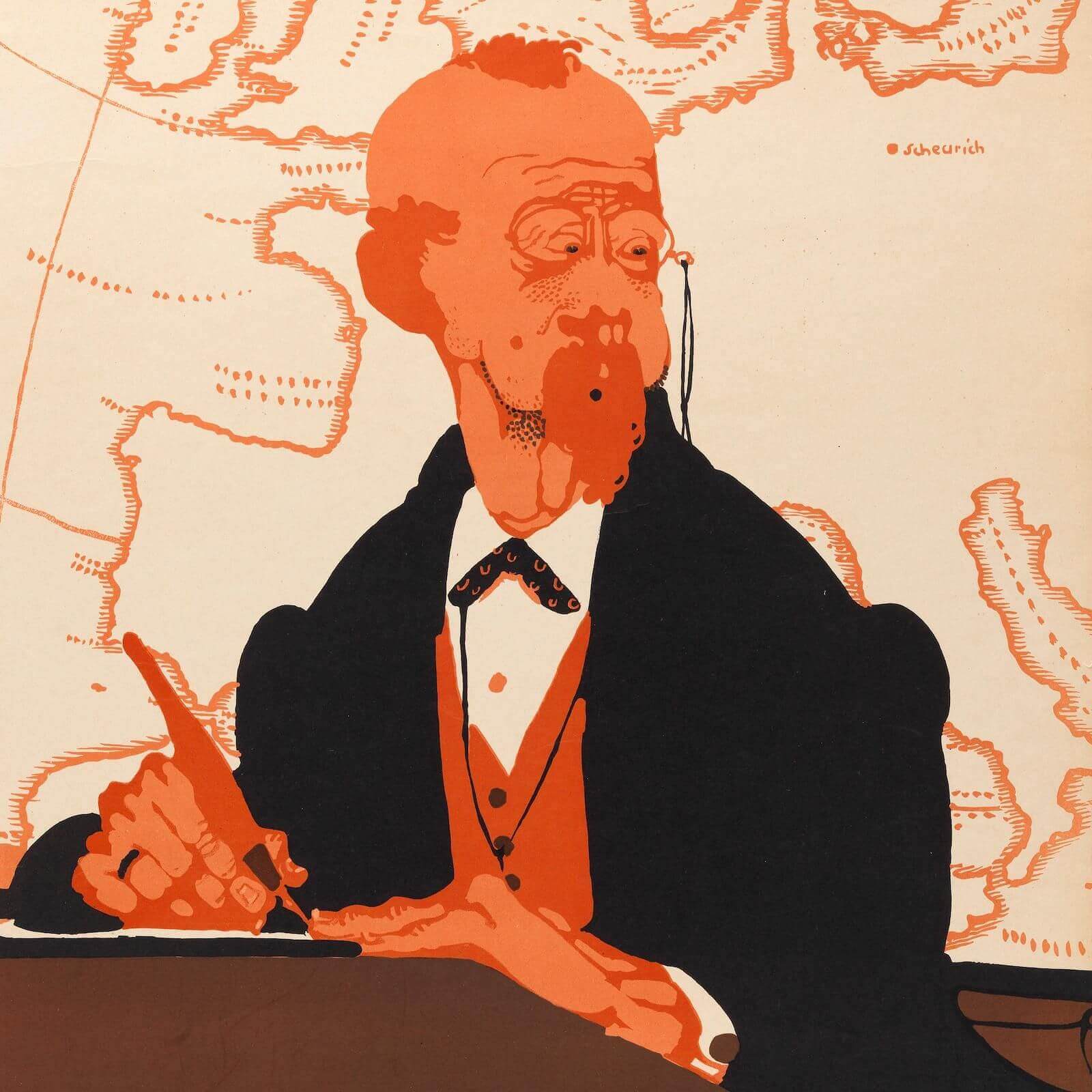

Image: A worried sedentary office worker needing a cure for haemorrhoids; advertising the “Stop” remedy for haemorrhoids. Colour lithograph by P. Scheurich, ca. 1910. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Public Domain.