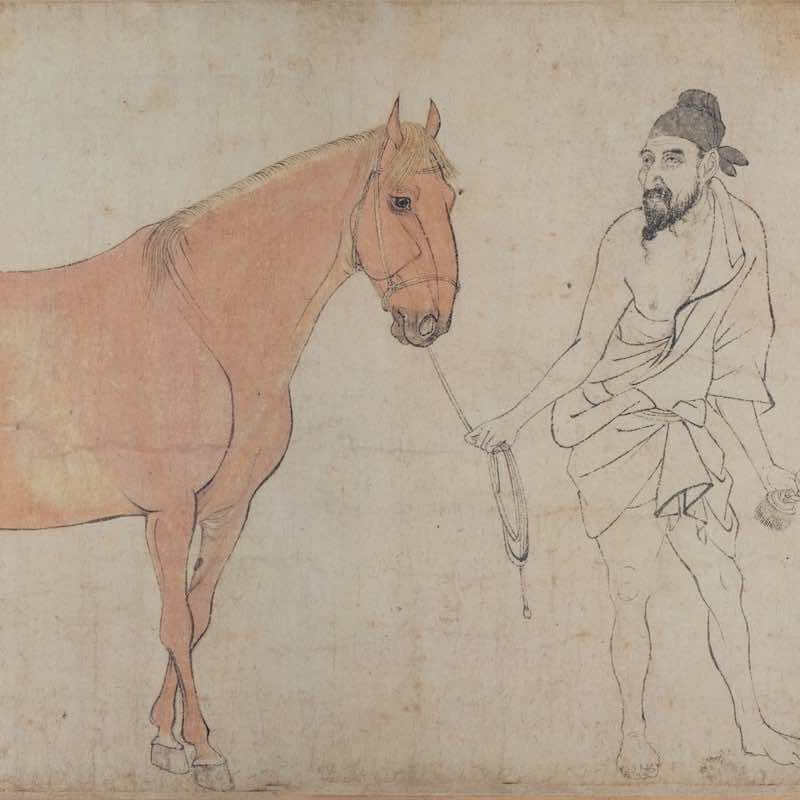

Lately, I’ve been thinking about training horses. Admittedly, this has been more of an abstract and philosophical concern than a practical one: generally I don’t have much to do with horses, and horses don’t have much to do with me, even though I sometimes go down to the meadows out of town and admire the beasts from afar. So whilst I haven’t been planning to pack in all the writing to take up the mantle of a horse trainer, I have been thinking about is the notion of horse-training as a metaphor for training more broadly.

It was a long time ago now that I first came across the Pāli text, the Bhaddāli sutta, and was charmed—or perhaps taken in—by its account of the virtues of horse training. Bhaddāli, according to the text, is a monk who is unwilling to subject himself to the monastic discipline, on account—the text tells us usefully—of being “like a fool, confused and blundering.” The Buddha then turns to him and asks the confused monk if he remembers a parable that he once told him about horse-training; and because Bhaddāli is a blundering fool (the kind of blundering fool for whom I have a natural sympathy), he has forgotten the parable, so the Buddha repeats it. Here’s an extract, in the translation by Bhikkhu Bodhi.

Bhaddāli, suppose a clever horse-trainer obtains a fine thoroughbred colt. He first makes him get used to wearing the bit. While the colt is being made to get used to wearing the bit, because he is doing something that he has never done before, he displays some contortion, writhing, and vacillation, but through constant repetition and gradual practice, he becomes peaceful in that action.

Next the horse-trainer puts a harness on the horse, which occasions further contortion, writhing and vacillation. But eventually the horse gets used to this too until it becomes a thing magnificent to behold.

When the colt has become peaceful in these actions, the horse-trainer further makes him act in keeping in step, in running in a circle, in prancing, in galloping, in charging, in the kingly qualities, in the kingly heritage, in the highest speed, in the highest fleetness, in the highest gentleness. While the colt is being made to get used to doing these things, because he is doing something that he has never done before, he displays some contortion, writhing, and vacillation, but through constant repetition and gradual practice, he becomes peaceful in that action.

The moral is clear: the Buddha goes on to liken the well-trained horse to the well-trained monk, who is “worthy of gifts, worthy of hospitality, worthy of offerings, worthy of reverential salutation, an unsurpassed field of merit for the world.” If you want to have those kingly qualities, if you want to prance and gallop, then you have to suffer a bit of contortion and writhing and vacillation. Bhaddāli is convinced by this argument, and goes away “satisfied and delighted in the Blessed One’s words.”

In many ways, this rings true. Certainly when I first learned to practice Buddhist meditation, I writhed and vacillated and contorted myself a whole load; but—having said this—over time found that I became “peaceful in that action.” And many of the things I have done in my life that have required a degree of training, or that have involved learning new things, have sometimes felt rather like this, involving a measure of writhing or vacillation or contortion in the process of learning to prance and gallop and charge with the highest fleetness and highest gentleness.

But I also can’t help wondering: are writhing, contortion and vacillation always necessary or desirable? Can one do pretty much the same thing, but without all this writhing about? Or—to go further—is this obsession with kingly heritage and fleetness something that should be resisted, precisely because of the writhing and vacillation that it involves? Let me try a counter-thought, moving from India to China, which I rediscovered the other day as I was rambling through the Zhuangzi. This is the translation by Burton Watson.

Horse’s hooves are made for treading frost and snow, their coats for keeping out wind and cold. To munch grass, drink from the stream, lift up their feet and gallop—this is the true nature of horses. Though they might possess great terraces and fine halls, they would have no use for them. Then along comes Bo Le. “I’m good at handling horses!” he announces, and proceeds to singe them, shave them, pare them, brand them, bind them with martingale and crupper, tie them up in stable and stall. By this time two or three out of ten horses have died. He goes on to starve them, make them go thirsty, race them, prance them, pull them into line, force them to run side by side, in front of them the worry of bit and rein, behind them the terror of whip and crop. By this time over half the horses have died.

This is a startlingly different view of the nature of horse-taming, and one that makes me think it is worth looking at my hitherto more or less uncritical view of the Bhaddāli Sutta afresh. The Zhuangzi doesn’t stop here, but—in the same way as the Sutta—makes the connection between sagely exhortation and horse-training; and yet the way that it goes about this couldn’t be more different.

Then along comes the sage, huffing and puffing after benevolence, reaching on tiptoe for righteousness, and the world for the first time has doubts; mooning and mouthing over his music, snipping and stitching away at his rites, and the world for the first time is divided… When horses live on the plain, they eat grass and drink from the streams. Pleased, they twine their necks together and rub; angry, they turn back to back and kick. This is all horses know how to do. But if you pile poles and yokes on them and line them up in crossbars and shafts, then they will learn to snap the crossbars, break the yoke, rip the carriage top, champ the bit, and chew the reins. Thus horses learn how to commit the worst kinds of mischief. This is the crime of Bo Le.

In the days of He Xu, people stayed home but didn’t know what they were doing, walked around but didn’t know where they were going. Their mouths crammed with food, they were merry; drumming on their bellies, they passed the time. This was as much as they were able to do. Then the sage came along with the crouchings and bendings of rites and music, which were intended to reform the bodies of the world; with the reaching-for-a-dangled-prize of benevolence and righteousness, which was intended to comfort the hearts of the world. Then for the first time people learned to stand on tiptoe and covet knowledge, to fight to the death over profit, and there was no stopping them. This in the end was the fault of the sage.

I love this passage from the Zhuangzi. I love the image of the sage “huffing and puffing after benevolence, reaching on tiptoe for righteousness”, because it is both funny and, I think, insightful. And whilst I recognise some truth in the Buddhist story, at the same time I can’t help thinking that when it is held up to scrutiny in the light of the Daoist story, there is a case to answer here. Indeed, I can’t help reflecting that I, too, have been guilty of “huffing and puffing after benevolence”, and that the results of this huffing and puffing have not always been very pretty.

Looking at these two starkly contrasting stories, I am not sure which to side with, or whether it’s possible to find a third position, some kind of Hegelian synthesis of the two. On the one hand, I find my taste for huffing and puffing after benevolence is less acute than it once was. Not only this, but the Buddhist story omits to say what happens to those colts who are not fine thoroughbreds, those wonky horses with matted manes who find themselves undergoing the discipline and then falling by the wayside.

But then, on the other hand, I wonder if there is a kind of appetite for training that is born not out of a desire to huff and puff after righteousness, or to transform oneself into something that one is not, but that arises instead out of a delight and fascination with the business of finding oneself here amid the ten thousand things of existence. In short, there may be more to life than drumming on one’s belly, cramming one’s mouth with food, and passing the time.

I don’t have any firm conclusion to offer here; but I wonder if, between the two stories, it might be possible to navigate a path in which training and education become matters of delight and fascination rather than the burden of the pole, yoke, crossbar and shaft. I wonder if it might be possible to think about a form of learning that harnesses our proclivities and tendencies, rather than one that attempts to supersede them. I wonder if we are too in love with the habit of difficulty when it comes to learning. And here—because it might seem that the Buddhists are coming off somewhat for the worse in this tale of two conflicting tales—let me finish with another story. Back when I was attending classes on elementary Pāli language, I studied with a monk in Birmingham. A small group of us would meet every week to get our heads around Pāli grammar. We’;d practice our conjugation of Pāli verbs out loud, reciting together. And before we started our recitations, the monk in question would give a grin and say, ‘OK, let’s play…’