I have spent most of the last two decades teaching the art of writing. And over the years, one thing I have encountered again and again is the myth that creativity necessarily entails suffering. This myth has deep cultural roots. We are smitten with the idea of the tortured artist. We love the idea that creativity is close to madness, that it takes us to the brink of the abyss.

This idea no doubt has a certain romantic charm. Sometimes I’ve fallen under its spell myself. After all, the idea that we are suffering can make us feel our labours are significant and weighty. It can give us a sense that what we are doing is meaningful.

But as something to emulate, the model of the suffering artist is next to useless. A. L. Kennedy, writing in the Guardian, puts it like this:

I have been trying to write for at least a quarter of a century, and I can say very firmly that in my experience, suffering is largely of no bloody use to anyone, and definitely not a prerequisite for creation. If an artist has managed to take something appalling and make it into art, that’s because the artist is an artist, not because something appalling is naturally art.

One reason that the idea of the suffering artist is so very pernicious is that it dulls our instincts for pleasure and delight. And it eclipses the central role that pleasure plays in creating anything of value. The myth of suffering for your art teaches us that pleasure is an indication that something is wrong, a worrying sign of our superficiality. And this idea is fatal for our creative well-being.

One artist who knew this was the Finnish writer, painter, and illustrator Tove Jansson (1914–2001). For Jansson, art was all about seeking pleasure. Pleasure wasn’t always present in Jansson’s own working life. But she knew that if you cared about good art, it was something you could—and you also should—work your way back towards. “Sometimes I’m happy about my book,” she wrote while working on her collection of short stories The Sculptor’s Daughter, “and sometimes I think it’s terrible. You know. But the main thing is I’ve been writing with pleasure…” (quoted in Boel Westin’s brilliant Tove Jansson: Life, Art, Words). Jansson saw pleasure as a sign her creative practice was going well. When there was pleasure, it was an indication that she was heading the right way.

Not that things were always easy for Jansson. She found the global success of her Moomin series of children’s books a burden. And an increasing sense of responsibility to her readers caused her to struggle with what she called the “pleasure — duty” problem. Sometimes these tensions made the creative process genuinely painful to her, something that entailed suffering. But for Jansson, suffering was never the point, nor was it the source of her creativity. Instead, it was a spur to a renewed search for lost pleasure, so she could go on creating.

But why does the myth of suffering as a spur to creativity persist at all, if it is so very destructive? One reason, I think, is that it conflates the idea of suffering and the idea of difficulty.

I am a writer by trade, and there are days when writing is a grind and pleasure seems a long way off. Writing is difficult. Anyone who has tried to put together a story, a poem, a novel, or a birthday limerick knows how difficult it can be (limericks are hard!). But difficulty is not the same as suffering.

Anything interesting or enriching or worthwhile you might choose to do with your life involves difficulty. Snowboarding. Playing the tuba. Learning a language. Bringing up children. Studying advanced mathematics. Difficulty is an inescapable component of doing worthwhile things. But difficulty is not always bound up with suffering.

It makes sense to avoid suffering as much as possible. Suffering is not creatively productive. But difficulty is a different matter. Where suffering tends to eclipse pleasure, difficulty can be a pleasure in its own right.

There is a prevailing orthodoxy that people like things easy. And yet for most of us, this isn’t true. We human beings relish difficulty, as long as it is the right kind of difficulty, as long as it is self-chosen and in line with our purposes and our intrinsic motivations.

When we are left to our own devices, free from external burdens, we don’t end up just sitting there taking it easy. Instead, we end up seeking difficulty for the sheer fun of it. We decide to write sonnets, or we take up the unicycle, or we spend hours learning how to conjugate Finnish verbs. In difficulty, and in the eventual mastery of things we once found difficult, there is endless pleasure, fascination, and excitement.

So if you want to create, then you need to do three things. First, avoid suffering as much as possible. Second, embrace difficulty and seek out the fun in it. And the third, commit yourself to the pursuit of pleasure, even in the midst of your difficulties. Because this quest for pleasure is the thread that will lead you where you want to go. It will lead you towards a deeper engagement with the world, and all the world’s richness. And it will lead you to the very sources of creativity.

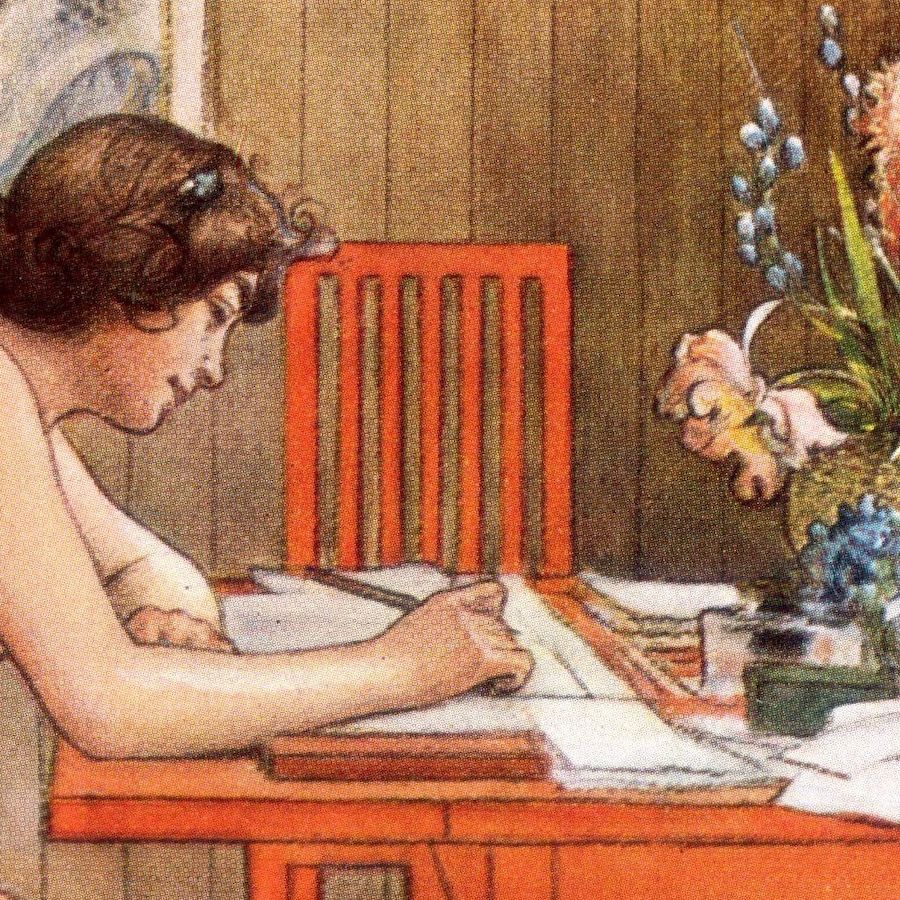

Image: Carl Larsson, model writing postcards (1906). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.