On Philosophy, Mountains and Finding Your Deepest Impulse

Sophie Grace Chappell is a philosopher, a poet, a mountaineer and a trans woman. She was born in Lancashire in 1964, and educated at Bolton School and Magdalen College, Oxford. She has taught at Oxford, UEA, Manchester, and Dundee. Since 1998, she has lived in Dundee with her family.

Her last book is Knowing What To Do (OUP 2014), and her next book is Epiphanies (OUP 2022).

Q: I’m always interested in how people end up becoming philosophers. What was it that led you to philosophy? And what keeps you doing philosophy?

Two things overdetermine both that I got into it, and that I keep doing it. One is that I’m an argumentative so-and-so. Like the chap in the Monty Python sketch, “I like a good argument”. I enjoy debate, and thinking things through, and getting the logical components interlocking smoothly in the machinery, or pointing out that in someone else’s machinery, they don’t interlock smoothly. The competitive or combative or aggressive aspect of philosophy. That’s the Rottweiler side of me, as I sometimes put it.

But there’s another side to me. I also have what you might—if you’re a Nigel Molesworth fan—call a Fotherington-Thomas side, a “Hello clouds, hello sky” dreamy poetic side. A mystical side maybe; certainly a contemplative side. And this moves me towards philosophy too, only from the other direction as it were. I want to do philosophy at the point where these two desires intersect: the desire to be precise and to call out imprecision and incoherence and flannel and posturing codswallop, and the desire to be transcendent, to say something that matters, that goes to the heart of things. I rather think that’s how Plato got to philosophy, too.

So of course you love it when you’re developing your own contemplative take on something. And if you’re gnarly-minded enough—I certainly am, and so was Plato—you love it too when you’re taking a combative approach to someone else’s contemplativeness. What I don’t enjoy—and Plato didn’t either!—is when someone gets all combative about my contemplativeness… which no doubt will happen when the book reviewers get to Epiphanies.

Epiphanies is a very Fotherington-Thomas sort of book. I have tried to Rottweiler-proof it, to some extent; I certainly want it to be a justification of a sort of contemplative approach to philosophy that stands up to scrutiny. But not much can stand up to a really determined—and unsympathetic—Rottweiler. When the reviews come out I’ll just have to suck it up, I guess. Serves me right for dishing it out to others so often, earlier in my career. (I like to think I’m less of a Rottweiler than I used to be, though maybe that’s just self-deception.)

Q: You are, as the Guardian has written, the UK’s only trans philosophy professor. I’d love to know about the deeper connections between your life as a philosopher and your identity as a trans woman. Has philosophy helped you make sense of these questions of identity? (And if so, how?)

What you immediately put me in mind of here is some remarks of Bernard Williams’ that I quoted in my Stanford Encyclopedia article on him. At the outset of his writing career (I said there), Williams took for his own “a phrase of D.H. Lawrence’s in his splendid commentary on the complacent moral utterances of Benjamin Franklin: ‘Find your deepest impulse, and follow that’” (1972: 93). Thirty years later he added, when looking back over his career, “If there’s one theme in all my work it’s about authenticity and self-expression… It’s the idea that some things are in some real sense really you, or express what you and others aren’t…. The whole thing has been about spelling out the notion of inner necessity.” Yes, that; very much that, about me and transgender. An inner necessity, a need to be authentically and above all openly who I actually am, is exactly what it’s all been about.

However, that doesn’t mean that I have a theory of transgender to offer. I doubt I do. For reasons I’ve been talking about in various publications, including Knowing What To Do and Epiphanies—and a lot of these reasons have quite a lot to do with lines of anti-theory argument in ethics that Bernard Williams pursued too—I tend to steer away from philosophical theories of anything, at least in those parts of philosophy that aren’t best understood as handmaids of science. I think the real truth of things often eludes systematisation; even in science too, actually.

And anyway, what is the theory supposed to do? Can we really not understand that murder is at least typically and maybe always wrong, or that love is usually a good thing, or that flowers are generally beautiful, till we have a philosophical theory that explains why? And what is “explanation” here? Why is some set of words, arranged in propositions with inferential relations between them, what we need to understand the goodness of love or the badness of murder? That seems to me an odd picture of what understanding is. Understanding, as I understand it, can be verbal and articulate, but quite often it isn’t at all, and oftener still the propositionally articulated bit isn’t the only part. Science limns the structure of reality, as Quine says in Word and Object. Sure it does, at least if it’s any good; but so does poetry too, if it’s any good. There isn’t just one correct way to grasp the deep structure of things; there are lots because there are lots of things we might call the deep structure of things. Propositional structures are great for the understanding, but experience matters too, and experience is no less cognitive for being, sometimes, non-discursive and not expressible in propositions.

Well, I feel the force of all these considerations about theorising about transgender in particular. It should be experience first, theory later—if at all. Also, with particular reference to this case of transgender, I am always saying—because I think it’s true—that trans people don’t owe cis people, or anyone else, an explanation of why they’re who they are; any more than gay people do, for instance, or black people or Jewish people, or any other historically stigmatised minority. Right now, there are far too many people saying that we who are transgender have to prove our right to exist before they’ll take us seriously or accept us as fellow human beings. That’s the demand of which I think it’s right to say that there should be no “transgender debate”. Our right to be ourselves is not up for discussion. We shouldn’t be refused admission to society until we’ve arrived at a theory of transgender that is “satisfactory” (to whom?).

At the same time, by and large cis people who haven’t personally encountered it don’t understand transgender. The commonest reaction is probably “OK, fine; I don’t get it, but live and let live”. And people like that do deserve an explanation, an account or an elucidation or a story about us because they’re not just trying to knock us down; their lack of understanding is benign, and not wilful.

To people like them, what I suppose I want to say is something like this. At least as I understand and experience it, being transgender is fundamentally about finding that your body is one way, in my case the male way, and you wish it were the other way, the female way. And if you’re transgender that wish, that longing, is not a whim or a passing fancy but an immensely powerful longing and yearning, and fundamental to your psyche. And it begins when you do. It’s not a sexual thing, it goes much deeper than that, and for a lot of us, me included, it’s among the first things we were ever aware of. And if it is there, you can’t make it go away by wanting to. I tried that, I saw it as my religious and moral duty to try, for 33 years, and the pressure of the repressed desire became absolutely intolerable. It was tearing me apart. So I had to try something else. So after a rather confused decade, from about 2008 onwards I tried living as a woman: presenting as female, living in society as a woman—or at least as a trans woman—and did it with gradually increasing confidence and openness.

Now it doesn’t solve everything to do that. I mean, if it’s fundamental to your psyche that you wish with all your heart that you’d been born female, but you’re perfectly well aware that you weren’t, then there’s only so much that can be done about that sense of mismatch. After a certain point, all trans people have to accept a compromise; the only question is where they’ll stop, and of course, the answers are different for different individuals. But what is clearly true is that no other solution comes anywhere near helping a trans person as much as it helps them to transition.

And if you’re young enough, and if there aren’t medical obstacles, no doubt that often means a full medical and surgical transition too. I was immensely struck by seeing on the internet recently the sheer joy that it gives trans men to have “top surgery”, to have their bodies realigned to fit more closely with their sense of who they are. To deny trans people this sort of bodily autonomy, this sort of choice over their own destinies—to insist that born biology is an unbreakable and unalterable destiny, that the body is what Plato thought it was, a prison—that seems to me the height of callousness and cruelty.

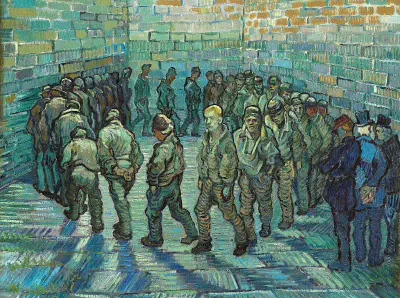

But here we are in the UK in a situation where in practice it takes at least 5 years even to get to the beginning of the NHS process of transgender healthcare, and where the same so-called “gender critical” voices that have pushed the vulnerable trans minority in our society into what is, for many individuals, a truly desperate situation—people are committing suicide because of the suffering their untreated gender dysphoria is causing them—those voices will be only too happy to make things even worse for transgender people if they get the chance. And they might well get the chance, given this government’s extraordinary willingness to engage in what they like to call culture wars. If only there were less of this sort of toxicity and cruelty around today.

Q: Contrary to the usual image of a philosopher as somebody sedentary, you have a fondness for extreme sports, in particular mountaineering. In what ways are philosophy and mountaineering alike? Or are they entirely different things?

Well, I talked about philosophising out of a coalescence of the instincts of a logician on the one hand, and of a mystic on the other. You get the same interaction of potentially conflicting impulses—and the same sort of resultant rows between people—in climbing. Climbing is, in a way, about solving problems in applied engineering. What application of what physical forces, at what angles, with what leverage and what counterpoising, will enable me to get this slow weak heavy body of mine to the top of this fantastic piece of smooth vertical rock? (Or, in winter, ice?) And how do I protect myself as I go? But in another way, you might say that climbing is not applied engineering at all; it’s more like a spiritual discipline—and it can be a mystical experience. I mean, if it wasn’t for the Wow Moments, the Peak Experiences, the Epiphanies, why would we climb at all? To keep fit? To attract sexual partners? I don’t really think so.

The truth is, of course, that climbing is both engineering and epiphany at once, and all my favourite writers on climbing register this bipolarity in one way or another. W.H.Murray for example, whose Mountaineering In Scotland is both the diary of a techno-wonk precisian (by the standards of his time: we’re a lot more techno-wonk-y now!) and also an elegy to a land he longed for. (It was famously written by Murray in a prisoner-of-war camp in Germany in 1944, on the only paper available to him, toilet-roll; the guards confiscated it, so he wrote the whole thing out again, on more toilet-roll.) Or again, my friend Stephen Venables—who is both a skilled woodworker and a passionate Chopin-player—writes wonderfully in his various books both about the technical side of climbing, and also about its epiphanic aspect. Or to name another friend, Simon Richardson combines almost mathematically exact route-descriptions with one of the most wonderful climbing-book titles I know, Chasing The Ephemeral. Climbing too is both technical precision, and also dreamy elevation. Maybe that’s why I love it in its different way just as much as I love philosophy—though I am definitely less gifted on the climbing side than in philosophy, that’s for sure.

On Knowing What to Do

Q: I want to talk about your book, Knowing What to Do, which argues for an approach to ethics that traces its roots back to Plato. But first, I want to ask about your own relationship with Plato’s thought. When did your interest in Plato begin? And why?

When I was growing up my family had in the house a copy of that old Penguin, The Last Days Of Socrates, with Apology, Crito, Phaedo in it. I expect it was my mother’s copy; she did an Open University degree in English and Philosophy in the early seventies, despite already having a Manchester University degree in English. So I suppose I started reading and rereading it when I was about 10. I was fascinated by the idea of “following the argument wherever it goes”, and both perplexed and excited by Socrates’ apparent confidence that that’s all you need to do to get to the truth. And the Socrates-versus-Plato dynamic intrigued me from the start. To use my terms above, Socrates was so clearly a Rottweiler, Plato so clearly a Fotherington-Thomas. I got on to the idea that there was a deep divide between them, all by myself. I didn’t need to read the scholarship, or to know it even existed, to see that Plato was putting things into Socrates’ mouth, in the Phaedo in particular. Because it just wasn’t—I reasoned—natural to suppose that we would get to those conclusions, like reincarnation and recollection and the Forms, simply by following our logical noses. Those are conclusions of revelation, not of reason; and being as I am a Christian, I was interested too in the question what beliefs you could get out of reason alone, and what beliefs needed revelation to support them. But Plato, I thought—and think—never really tried, in the Phaedo, seriously to suggest that he was getting his “Socrates” to his conclusions by reason alone. There was plenty of “as we know from those old-familiar arguments of ours” to be found in the text. Plenty of appeal, too, to dreams and prophets and fairy-stories.

Another thing that interested me straight away in the arguments in Plato’s dialogues—I’m afraid it’s a bit meta—was about, so to speak, the granularity of the arguments. Socrates is very keen to proceed a single step of argument at a time. But what counts as a single step in argument, and why? Is logical space basically a continuum, so that anyone who defines minima, pixels, atoms, unitary steps, within logical space is making a particular decision about how to carve things up that could have been decided otherwise? Or is logical space naturally and essentially pixellated, atomic, granular?

At any rate it was very obvious to me, when I read Plato, that what struck him as a basic unit of inference, what he counted as a single step in the argument, was different from what strikes us today. So what followed from that difference? Well, it meant either that Plato had things all wrong—he was dividing logical space up incorrectly. Or that we have it all wrong, and Plato was right. Or that we and Plato are both wrong, and some third account of the basic structure of logical space is available elsewhere, or is yet to be discovered. Or again, perhaps, that the very idea of logical space is a relativistic notion. That what you count as a single step in argument is determined by some feature of your context. But then, if so, which feature?

The obvious suggestion is of course that it’s our languages that do the relativising. But if that’s right, then a whole research agenda hoves into view: we need to think about how the language that we do philosophy in, affects—perhaps even determines—the philosophy that we’re able to do. I didn’t really have the vocabulary to express all this clearly when I was 12 or 14 (perhaps I still don’t). But I do think these considerations give us one reason why it’s essential for philosophers not to be monoglots. We should always be wary of the language that we work in, whether English or German or propositional calculus or whatever. We should never allow people to talk about “ordinary-language philosophy” or “linguistic intuitions” without retorting “Which language?” We should never stop pushing the question “What does my own medium for thought obscure from my own thinking?” I think this wariness about language and logic is one of the best things that reading Plato in Greek can give you. Though of course you can also get it by reading Kant in German, or Descartes in French, or Augustine in Latin. Or Laozi or Advaita Vedanta in Chinese or Sanskrit (I don’t read either, unfortunately).

So these were aspects of Plato’s works that interested me straight away when I was 10 or 12 years old—and still interest me today. Above all: the idea of getting to the Platonic heaven simply by question-and-answer argument: well, wow. It might not actually work, but what an incredible wheeze. I say something about that, too, towards the end of Epiphanies.

Q. At the outset of Knowing What to Do, you talk about the failure of systematic moral theories. What are systematic moral theories? And why do you think they fail?

A systematic moral theory is, roughly, an approach to thinking about what to do which derives conclusions about what to do in particular cases from the most general possible principles about what to do in any case whatever, and which aspires to give the greatest possible number of explanations and justifications of action on the basis of the smallest possible of theoretical posits, axioms, or assumptions. The most familiar examples of systematic moral theory in this sense are the various forms of Kantianism, consequentialism, contractualism, natural law theory, and so on; virtue ethics can sometimes be presented as a systematic moral theory too.

I say more—a lot more, 220,000 words more—about all this in Epiphanies. But very briefly, a theory like that fails for reasons that Bernard Williams and David Wiggins put very well in this passage from their introduction to Aurel Kolnai’s collected essays:

In science theorists hope to find a few principles from which everything else will be deducible. There are more serious reasons than purely aesthetic for wanting that—clarity, the hope that the drive towards it will reveal error wherever it exists, the subsumption of many diverse phenomena under one satisfying description. But in the case of moral philosophy what defines the subject is a highly heterogeneous set of human concerns, many of them at odds with many others of them, many of them incommensurable with many others of them. In this case there is no reason to think that what is needed is a theory to discover underlying order. This is not a subject after all where very much is hidden. Or rather what is hidden is hidden in a psychological or interpretive sense. There is no question of a secret axiological ordering principle. There is no deeper level of reality, comparable to the microscopic or sub-microscopic level explored by chemistry and physics, which it is the moral philosopher’s duty to probe. And where one can make no sense of there being such a level, the idea, urged by some moral philosophers, of finding the “simplest theory” which “will save the phenomena” (in the normal acceptation of the phrase) is nearly meaningless.

Q: As an alternative approach, you talk about the moral imagination. It might be tempting to boil this down to something systematic as well; but your own position seems much more baggy, generous and unsystematic. So, speaking unsystematically, what do you mean by moral imagination?

This is difficult to answer briefly, because, yes, I am speaking unsystematically when I talk about moral imagination. I mean lots of different things by the phrase. In Chapter 2 of Knowing What To Do I picked out three. One is something like empathy, the ability to put yourself in someone else’s shoes; I get into that by beginning from a contrast between two people encountering an alien race—one of them is Patrick Leigh Fermor and the other is Adolf Hitler. The other two things I mean are in different ways both about the ability to question the framing of a moral question, in particular a moral question that is presented as a dilemma that is supposed to lead us to general theoretical conclusions, like ticking-bomb scenarios or trolley problems. About problems like that I find I very often want to say “Never mind what the answer is; why are we accepting the question?” Why, that is, should we accept the whole way the problem is framed for us, as if there were something neutral or inevitable about that? That, as Wittgenstein might put it, is where the sleight of hand, the conjuror’s trick, has happened already: in the way the question was set up, which, unfortunately for us, we never thought to query. In this sense I think contemporary moral theory is full of leading questions. And I’m deeply suspicious of leading questions.

By saying that we can pick out these three kinds of moral imagination, I didn’t at all mean that they’re the only kinds. Far from it. And in any case, another thing I’m deeply suspicious of in contemporary moral theory is allegedly comprehensive catalogues of types of things; they almost never turn out to be truly comprehensive, and then people contort themselves gratuitously to save the quite unnecessary assumption that they have to be comprehensive. But there are other possibilities for what we might mean by “moral imagination”. In the new book, in Epiphanies, I have a fair bit to say about how the imagination feeds off, is psychically nourished by, the kinds of permanent image for the soul that Jung calls an archetype; this happens with art and religion in particular. But also, and I developed this idea in the last chapter of Knowing What To Do, simply to truly understand anything that confronts us is an exercise of the imagination, too: it is a kind of Murdochian attention or attentiveness.

Q: One of the things that you get from Plato is the role of contemplation in developing moral imagination. What does it mean to contemplate? And how do you go about it practically?

Like I say, it’s about attention, about fixed and undivided still gazing upon something. Murdoch talks about this in The Sovereignty of Good, and it’s hard to improve on what she said there. It’s a spiritual discipline; it’s an encounter with reality; and it’s a kind, perhaps the central kind, of love. We fix our minds with an effort at love and truthfulness and justice on what is there, what is really there, before us. To understand is to become still to ourselves, and still in ourselves; and alive to the object of attention, outside our selves. This is also, I think, what poets do, or try to do. It’s certainly what I attempt in my own poetry.

Is it too pretentious to try and show what I mean by citing, indeed reciting, a poem that I wrote? This poem is about two of my own children as pet-keepers, and how I saw, in them and in their care for their pets—as it happened to be, a goldfish and a stick-insect—just this kind of contemplative love.

Two pets

The power of human sight. The hanging hawk is only awaiting prey, but turns, observed, to picture, image, symbol; becomes framed. The power of human focus, of the rapt attent that constellates the sky and names the species, that populates the peaceful empty fields quiet with cow-pats and the small life of birds.

Or how a blank-eyed pebble-turning fish, bobbing in plastic weeds its simple scales, or furtive exoskeletal invertebrate, six legs and mouth-parts, stalking unawares within a human ten-year-old’s arc-light awareness, is turned into a burning-point of love; is seen and by this concentration made something very good.

Q: As we are talking about moral imagination, it strikes me that the inability to accept the experience of those who identify as transgender is, in large part, a failure of the moral imagination. If so, how do we move forward from here?

I think that’s right: the debate has got bogged down in a kind of dogmatism, a kind of refusal to listen to transgender people. How do we move forward? Well, we stop refusing to listen, and start listening.

One very obvious arena where this needs to happen is the British press. The papers at present are full of articles about transgender people; but these articles are hardly ever by transgender people. Our voices are ignored or suppressed, and we personally are demonised and dehumanised. There isn’t a subtle or complicated solution to this problem. It just needs to stop. It simply needs to change.

On Friendship, Epiphanies and Writing and Reading What You Want

Q: What’s next on the horizon for you and your work?

Epiphanies will, I hope, be out before too long, and certainly in 2022 at the latest. It’s a book about peak experiences, Wow moments and Aha moments, and what they might be for ethical philosophers; how we might build a philosophical outlook that takes these experiences seriously. So that’s in the pipeline. So too is a volume of my poems! Songs For Winter Rain; I’m not sure when that will actually appear, but fairly soon, I think. It has “Two Pets” in it.

Philosophically, right now, I am thinking about how to take forward the philosophical programme that Epiphanies advances. It’s the same programme as I was already pursuing in Ethics and Experience and Knowing What To Do, only, as Hegel would say, things come to self-consciousness as they unfold. You get clearer about what it is that you’re trying to do, as you carry on doing it.

There’s also a short book on Friendship to be written, contracted to CUP. How that will go, and how much it will connect with the philosophical agenda of Epiphanies, I really have no idea. I’m certainly not going to force the friendship book to be somehow on the same page as the stuff on epiphanies. Maybe it belongs there and maybe it doesn’t; who knows?

This is the great thing about philosophy, and what keeps me going at it: it’s so unpredictable. I simply have no idea where the argument might lead me. But nearly always, so far, to a good place.

Q: Finally, if you could give any advice to an aspiring philosopher, what would it be?

Two things, I think. They both sound a bit defiant-individualist, and I don’t want to lean too far into that, because philosophy is and should be a dialectical and conversational enterprise, and so it does matter what feedback other people give you.

However, philosophy as it is—I mean mainly academic philosophy, but it’s more widely true than that—is a real hall of mirrors: everyone is looking for everyone else’s approval all the time, and that kind of peer pressure becomes not just intellectually stultifying but institutionally tyrannical as well.

So first, read the books and papers, and write the books and the papers, that you want to read and to write, not that other people tell you to.

And secondly: don’t measure yourself by other people’s measures of status. Don’t play the hall of mirrors game. What matters is whether the work you produce is any good. Measure yourself by that. And while philosophy is unendingly difficult and demanding, don’t be too hard on yourself.

Sophie Grace Chappell is Professor of Philosophy at The Open University.

Further Reading

Selected Books

Ethics and Experience: Ethics Beyond Moral Theory. Acumen, July 2009.

Knowing What To Do: Vision, Value, and Platonism in Ethics. Oxford University Press, March 2014.

Ethics beyond the limits: new essays on Bernard Williams’ Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy, edited Sophie Grace Chappell and Marcel van Ackeren. Routledge 2018.

Epiphanies. Submitted to OUP (forthcoming 2022)

A Philosopher Looks at Friendship (Under contract with CUP)