For Plato, divination is always tied up with madness — but that it is not to diminish it. Instead, as far as Plato is concerned, divination may be a necessary madness. This is what Plato writes in Timaeus (71e):

The claim that god gave divination as a gift to human folly has good support: while he is in his right mind no one engages in divination, however divinely inspired and true it may be, but only when his power of understanding is bound in sleep or by sickness, or when some sort of possession works a change in him.

Nobody in their right mind engages in divination. The connection between being out of your right mind and divination appears again in the Phaedrus (244 b-c), where the greatest goods comes from madness (or μανία).

The people who designed our language in the old days never thought of madness as something to be ashamed of or worthy of blame; otherwise they would not have used the word ‘manic’ for the finest experts of all—the ones who tell the future—thereby weaving insanity into prophecy. They thought it was wonderful when it came as a gift of the god, and that’s why they gave its name to prophecy; but nowadays people don’t know the fine points, so they stick in a ‘t’ and call it ‘mantic.’

Divination plays a recurrent role in Plato’s accounts of philosophy. But it is a curious role, because it involves being out of your right mind. Flirting with divination is flirting with madness, because divination is something that is hard to account for, hard to make sense of, and something that gives rise to a weird kind of knowing.

Socrates as diviner / μάντις

This raises the question of the connection between madness and philosophy. In his paper “Plato on Madness and Philosophy” (Ancient Philosophy 31.1 (2011): 47–71), Daniel Werner talks about the Phaedrus, and says that the madness proper to the philosopher is “that of possession by the divine Forms. "

Like the poet, Socrates invokes the Muses as the external source of his speech-making (237a7-b2), saying that his breast is ‘full’ (235c5), that he is ‘filled like a vessel from outside streams’ (235c8-d1), and that he is in the grip of ‘some divine experience’ (238c5-6) and is ‘possessed’ (263d3); like the Pythia, Socrates describes himself as a μάντις (242c4), and at the end of the dialogue offers a prophecy regarding Isocrates’ fate (278e10); and like the Bacchic initiate, Socrates says that he is ‘beside himself’ (234d2) as he joins Phaedrus in an ecstatic frenzy (228b8, 234d5-7), and later ‘purifies’ himself by way of the palinode (243a1). We ought not to conclude from these statements, as some commentators have, that Socrates is literally ‘inspired’ when he delivers his speeches or that he is in some literal state of frenzy during the course of the dialogue. Rather, Plato’s point is to make Socrates appear as such, as a way of indicating that the truest and best kind of poetry, prophecy, and catharsis is by way of philosophy (as exemplified here by the character Socrates).

Although he says he is navigating between “literal” and the “ironic” readings of Socrates’s frenzy and madness, I wonder if Werner underplays things. It’s hard not to think that there’s a persistent tendency among philosophers to tame the strangeness of philosophy in general, and of this divinatory, inspired Socrates in particular. This reasurringly makes Greek philosophers more like us, and makes the tradition less, well, weird.

Strange philosophers

But if he lurched into a contemporary philosophy department in a university somewhere or other, Socrates would probably be a pretty baffling figure. Socrates the misfit, the oddball, the weirdo, squat and ugly and ill-mannered. He wouldn’t fit in. The university would probably call security to have him evicted.

Here’s Pierre Hadot in Philosophy as a Way of Life (p. 57)

By the time of the Platonic dialogues Socrates was called atopos, that is, “unclassifiable.” What makes him atopos is precisely the fact that he is a “philo-sopher” in the etymological sense of the word; that is, he is in love with wisdom. For wisdom, says Diotima in Plato’s Symposium, is not a human state, it is a state of perfection of being and knowledge that can only be divine. It is the love of this wisdom, which is foreign to the world, that makes the philosopher a stranger in it.

Werner’s reading of the strangeness of Socrates is to say, more or less, that while philosophers may be weirdos, they are pretty weird kinds of weirdo. The μανία or madness of the philosopher is not everyday madness.What makes the philosopher mad, otherworldly, atopos (Werner writes) is that they are intoxicated with the Forms. From the point of view of the everyday non-philosopher, it is clearly a kind of madness—and perhaps indistinguishable form other kinds. Which is why in the philosopher heading back down into the cave invites ridicule.

And before his eyes had recovered—and the adjustment would not be quick—while his vision was still dim, if he had to compete again with the perpetual prisoners in recognizing the shadows, wouldn’t he invite ridicule? Wouldn’t it be said of him that he’d returned from his upward journey with his eyesight ruined and that it isn’t worthwhile even to try to travel upward? And, as for anyone who tried to free them and lead them upward, if they could somehow get their hands on him, wouldn’t they kill him?

But from the point of view of one who is similarly intoxicated with the Forms, or with truth, the madness lies elsewhere: with the ones who are stuck in the cave.

There’s something queasy about this idea that philosophers are bound to be misunderstood and mocked for their strangeness because they are, ultimately, concerned with higher, better things. It lets people off the hook for all kinds of unwelcome behaviours. Crazy wisdom &c. But on the other hand, I’m sympathetic to the idea that the business of thinking better about the world may involve all kinds of strangeness—if only because our minds are not built to process the world without this strangeness, so we might as well harness it.

The weirdness of divinatory knowledge & methods

And this leads back to divination. Because divinatory knowledge and methods are definitely weird. Plato acknowledges both the necessity of these kinds of knowing, and their strangeness. Divination is a strange, perhaps necessary, but nevertheless unsettling way of knowing.

It seems there’s a phenomenological dimension to the strangeness here. Those who use divinatory methods report these methods seem uncanny. They seem to have an efficacy that is hard to account for (for those who are committed to them at least). They help us tap in—as Peter Struck puts it in his Divination and Human Nature (Princeton University Press, 2016)—to surplus knowledge, or to “those things we know without quite knowing how we know them.”

This is one of the things that interests me about divination. On the one hand, while in their right mind, no one engages in divination. But on the other hand, engaging in it may be nevertheless useful (if we care about what it means to be in our right mind).

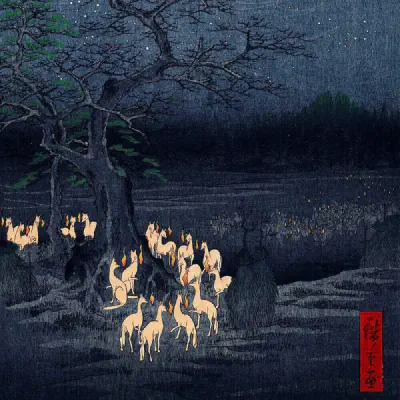

Image: Delphic Sibyl, British before 1626, Public Domain via Google Art Project