Does philosophy change our minds?

Philosophers talk a lot about the power of reasoned argument to change our minds. The whole discipline of philosophy, to an extent, depends on the idea that this is how argument works.

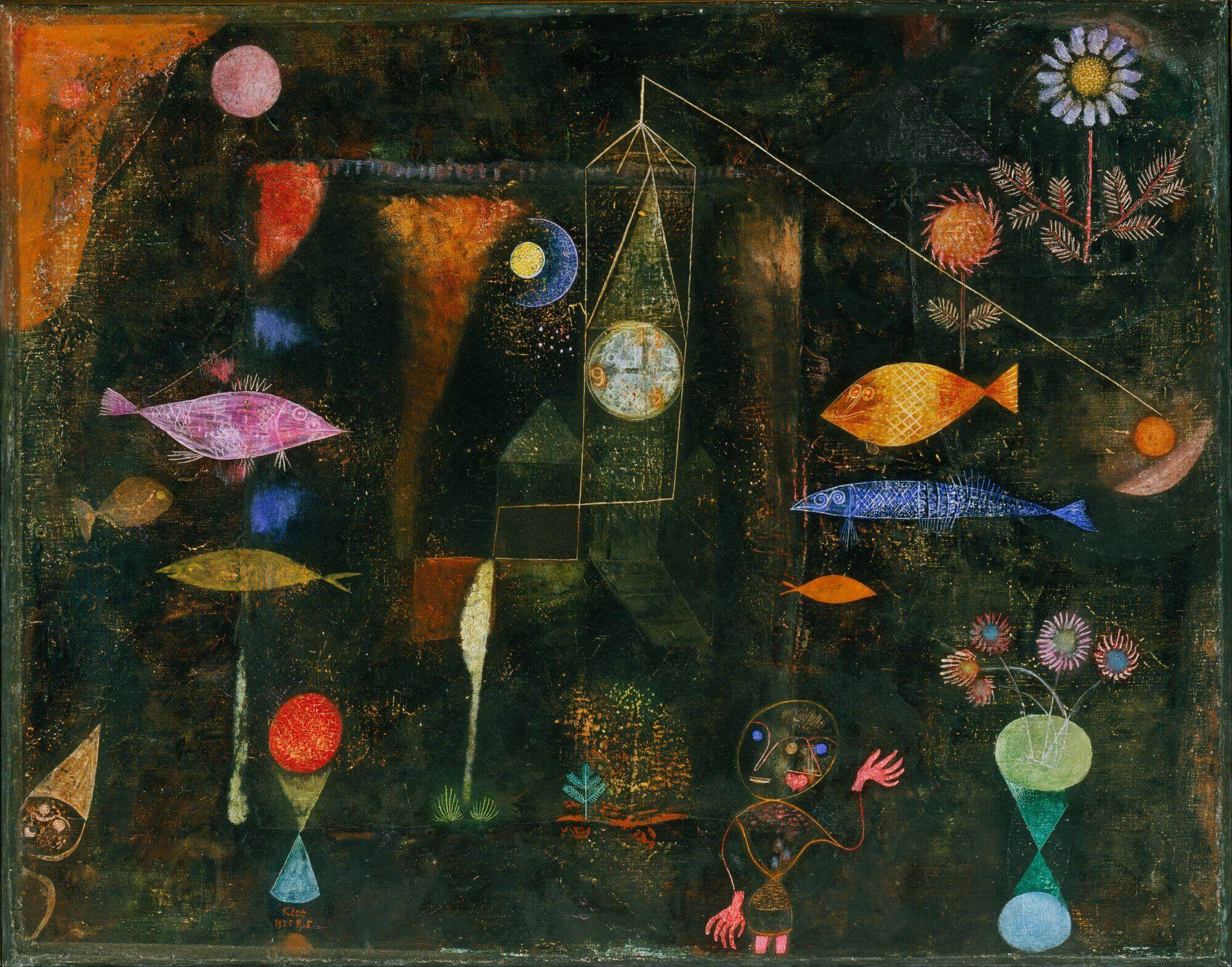

But there’s a problem with this idea. Because one thing that you notice if you hang around philosophers for a while is that in practice, they don’t change their minds very often. Surely, one might think, if reasoned debate were really this transformative, then their skill in the use of reason would lead to them changing their minds with a quicksilver frequency that would put the rest of us to shame. They’d be hard to pin down, slippery as fish, constantly on the move. But it doesn’t seem to work like this. Instead, philosophers (or at least the ones I know) seem, if anything, to change their minds less than non-philosophers.

Perhaps this is not surprising. Philosophers spend a lot of time and energy defending their arguments. And after all this effort, when everything that you thought you knew turns out to be wrong, or when the edifice of your beliefs begins to crumble, then it’s hard to face up to this. There’s something uniquely difficult about changing your mind, even more so when you have staked your entire life and reputation on a particular set of arguments or beliefs. Changing your mind can make new enemies of those who once considered you a friend. And it can invite ridicule. Think of how politicians are held to account by the media for changing their mind, and how these reversals are referred to as “humiliating U-turns.”

So in this philosopher file, we’re going to look at two philosophers from the ancient Greek world who changed their minds. The first is Timocrates of Lampsacus (born around the late 4th century BCE), who turned his back on the philosophy of Epicurus. And the second is the Dionysius the Renegade, his rough contemporary, who embraced, and then turned his back on, the Stoic school of Zeno.

Timocrates renounces Epicureanism

For the Epicurean philosophers, pleasure is the highest good. To put the philosophy in a nutshell, for the followers of Epicurus, there is no other good but pleasure. This being the case, we need to get smarter about pleasure. After all, the Epicureans argued, pleasure is not something we’re very good at. Many of the pleasures we seek entail pain and discomfort. We seek pleasure and end up with the opposite. So a life dedicated to pleasure is one where we need to think harder about the pleasures we seek, and distinguish between them more carefully.

Timocrates became a member of the Epicurean community, along with his brother Metrodorus. Timocrates’s brother was one of Epicurus’s closest friends, but Timocrates himself was less impressed by Epicurus and his followers. He left the sect, unconvinced by the claim that pleasure was the highest good. Having left the school of Epicurus, Timocrates wrote a work called On Nature. The book contained furious attacks on Epicurus. He claimed that Epicurus was poor at reasoning, tediously repetitious in his writing, given to over-indulgence to the point of vomiting, disdainful of pretty much everyone, and addicted to sensual pleasures.

Unsurprisingly, this led to a rift between the two brothers (there’s nothing that the history books like more than tales of two warring brothers). Diogenes Laërtius tells us that Metrodorus remained a disciple of Epicurus, and he wrote furious refutations of his brother’s accusations, including a book called Against Timocrates.

It’s hard to know how much credit to give Timocrates’s criticisms. Although similar charges against Epicurus were repeated for centuries afterwards, many of them drawing on Timocrates’s lurid accusations, other accounts of Epicurus’s life and person paint a picture of Epicurus as much more restrained and abstemious. And as Timocrates’s On Nature has not survived, we don’t know what kind of philosophy he embraced after leaving Epicurus’s school. Diogenes does say, however, that Timocrates made a “minor career” out of pouring slander on Epicurus.

Dionysius renounces Stoicism

Timocrates’s contemporary, Dionysius the Renegade, had a conversion that was in some ways the mirror-image of that of Timocrates. Dionysius started his philosophical life as a follower of the philosopher Heraclides Ponticus, a man whose brilliance was only matched by his pomposity.

However, Dionysius and Heraclides fell out after Dionysius perpetrated a literary hoax. He claimed to have discovered a lost work of Sophocles, although he’d actually authored the play himself. Heraclides was taken in, and he cited the forgery in his own work, sure that it was authored by the great playwright. At this point, Dionysius confessed to the hoax. Unwilling to admit he was wrong, Heraclides insisted that the work was genuine. It was only when Dionysius revealed an acrostic hidden in the text claiming that Heraclides was an “old monkey”, who was “ignorant of literature” that Heraclides had to admit he was wrong. [1]

Heraclides was furious at being taken in so easily. Unsurprisingly, the hoax led to the two of them parting ways. Next, Dionysius became a follower of Zeno of Citium, the founder of the Stoic school. Stoicism emphasised the pursuit of virtue over the pursuit of pleasure. The goal of Stoicism was an understanding of necessity, and an imperturbable, steady and unwavering commitment to living in accord with virtue. This seemed to have served Dionysius well for a while, until he came down with a terrible eye infection.

For another philosopher, this might have been a chance to put his Stoic commitments to the test, to tough it out. But Dionysius chose otherwise. He left the Stoic school, and instead became a member of the Cyrenaic school who, like the Epicureans, emphasised pleasure.

For the Cyrenaics, pleasure was defined as the “smooth motion of the flesh” (this contrasted with the Epicurean view of true pleasure as being essentially static). And for somebody afflicted by physical pain, perhaps the philosophy of the Cyrenaics was appealing to Dionysius: it may have provided a way forward that was not simply about bearing the suffering of his infection, but was instead about cultivating what pleasure he could.

Predictably, the Stoics were no less outraged by his defection than the Epicureans were by the defection of Timocrates (despite all that Stoic training in imperturbability). They claimed Dionysius had fallen into vice and indolence (much the same claim that Timocrates levelled against Epicurus), that he spent the remainder of his days frequenting brothels, and that he was only interested in sensual pleasure.

Once again, it would be good to have access to Dionysius’s own words to better appreciate his later phase philosophy. He wrote books both during his Stoic and during his Cyrenaic years, including On Apathy and On Pleasure. But none of these books has survived.

Changing your mind

What can we take away from these stories of renegade philosophers?

The first thing we can take away is that stories like these point to the cult-like fervour of various philosophical traditions in the ancient Greek world. The savagery of criticism and the extraordinary bitterness of disputes on both sides – particularly when philosophers like Timocrates and Dionysius went rogue – puts even contemporary university philosophy departments to shame. And that is saying something.

The second thing is the idea that the trajectories of individual philosophers in the ancient world were often more existentially charged, more messy, and more turbulent than our romanticised views of ancient truth-seekers. Sibling rivalry and jealousy, the hunger for status, character clashes, eye infections and other bodily ailments, the accidents of chance and of personal biography… all these things were part of what drove philosophers, then as now.

And finally, perhaps, these stories remind us that although philosophy claims to be about changing our minds, the history of philosophy has not necessarily treated well those who have radically changed their minds. So be warned. If you are a philosopher, you go rogue at your own risk.

Notes

[1] This entertaining story is told in Lives of the Philosophers: Diogenes Laertius, translated by Pamela Mensch (Oxford University Press 2018), e-book.