Life

Where does philosophy begin?

If you ask a Western philosopher, they might say ‘with Socrates.’ If you ask a Chinese philosopher, they might say, ‘with Confucius.’ And of course, the question ‘where does philosophy being’ is a flawed one: the love of wisdom — this business of asking questions about life and existence — has no real beginning. Human beings have always found themselves wondering about the world of which they are a part, wrestling with the strange, baffling business of being alive.

But if you wanted to find a candidate for one of the earliest named philosophers, you would need to go back long before Socrates and Confucius. Because one of the earliest philosophers whose name is still familiar to us comes from Africa, and lived around four and a half thousand years ago.

The philosopher-politician

This early philosopher was called Ptahhotep, and was the first minister to the Pharaoh Djedkare Isesi in the late 25th century BCE. Ptahhotep had multiple roles in government, including responsibility for overseeing the state treasuries, and overseeing the scribes who worked for the Pharaoh.

Today, Ptahhotep is known mainly for his book, The Maxims of Ptahhotep, one of the greatest examples of early Egyptian wisdom literature. In his Maxims, Ptahhotep says that he is already old, and he petitions the Pharaoh to be permitted to retire from his post, so that he can be replaced by his son — a request to which the Pharaoh agrees. The philosopher then sets out the wisdom that he has gleaned over his long life, and that he wants to hand on to his son.

Philosophy

Written when Ptahhotep was old and decidedly grumpy, the Maxims make for entertaining reading. Ptahhotep begins complaining about the miseries of old age. He grumbles that he forgets things all the time and ‘cannot recall even yesterday.’ He says he no longer has any vigour, and has to nap all the time like a child. And he laments that all his previous pleasures have lost their savour. ‘Even standing and sitting are a bother!’ he says.

But, he concedes, age comes with its benefits; and one of them is wisdom. So in the Maxims, he aims to communicate to his son what wisdom he has gleaned in his life and career. Because, after all, ’no one is born wise.’ And in the quest for wisdom, we need all the help that we can get.

Wisdom is always incomplete

It is at this point that the Maxims get interesting. As such a high-ranking individual, Ptahhotep could have chosen to present himself as an authority. But instead, he goes in the other direction, and he calls authority itself into question.

Old and grumpy as he is, Ptahhotep is sceptical when it comes to the possibilities of human attainment. ‘No one has ever attained perfection of competence,’ he says. ‘And there is no craftsman who has acquired (full) mastery.’ In other words, we all are (and always have been) at best semi-competent at this business of living; the mastery that we crave is always just out of reach.

This makes Ptahhotep a sceptic about the wisdom of those who claim to be wise. And in this, he resembles Socrates who lived two millennia later. But — unlike Socrates — Ptahhotep also recognises that there is such a thing as wisdom to be found among his contemporaries, and that this wisdom can be found in surprising places. Good advice, he says, ‘is rarer than emeralds,’ and these emeralds of good advice can be found not just among priests and scribes, but also among those who are unlearned, and among ‘women at their grindstones.’ Within the patriarchal society of Ancient Egypt, this is a strong claim.

Ma’at: the foundations of ethics

Reading the Maxims of Ptahhotep, you get a sense of a real, human voice trying to make sense of the world, and trying to navigate through complications of human life. And if Ptahhotep’s advice often seems rather home-spun, it is underpinned by a larger idea: the idea that the universe runs on moral principles.

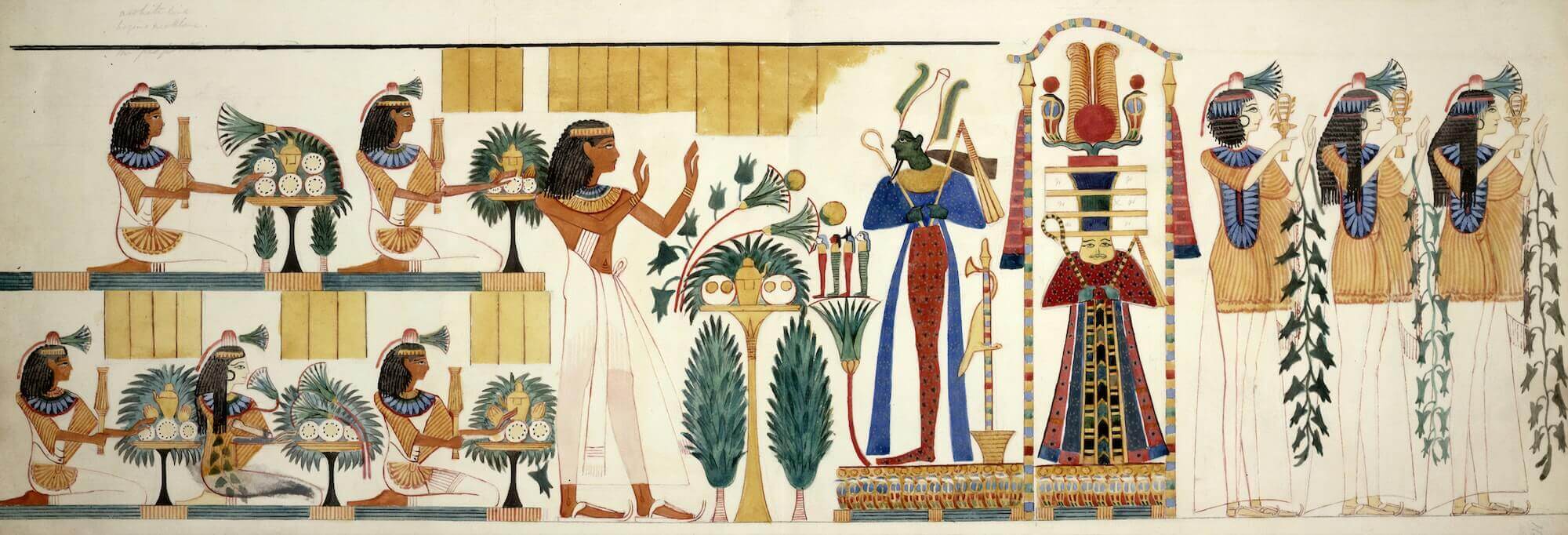

For Ptahhotep, the moral order of the universe is guaranteed by the goddess Ma’at, the embodiment of harmony and social order. It is Ma’at who brought order to the world after its creation; and she is the one who is responsible for maintaining this order, preventing the world from sliding back into primordial chaos.

The name Ma’at literally means ‘base’, like the base of a throne. The historian Norman Cohn writes that Ma’at was ‘a principle of order so all-embracing that it governed every aspect of existence.’ For Ptahhotep, Ma’at is the foundation-stone and guarantor of the moral order of the world.

Ptahhotep argues for a moral universe. But this presents him with an obvious problem. If the universe is moral, how is it the case that self-interest seems to lead to gain and profit? Ptahhotep’s response to this problem holds fast to the idea of a moral order to the universe, but is not entirely convincing. He argues that such gains are only ever short-term. What those who do immoral acts don’t realise is that ultimately ‘wrongdoing does not result in success’; because, he writes, ‘in the long run it is Ma’at which endures.’

Advice for living

The Maxims are full of advice about how to manage our lives in accord with this moral order, both individually and in relationship to others. Ptahhotep advises us not to work too much. What is important in human life is ’the time of following the heart.’ And when we accumulate wealth for its own sake — beyond what we need to keep our ‘household in order’ — we squander this time of following the heart, and this squandering is an ‘annoyance of spirit.’

Follow your heart as long as you live,And do not work beyond what is allocated (to you).Do not waste the time of following the heart,For wasting time is an annoyance of the spirit. — The Maxims of Ptahhotep.

As for our relationships with others, Ptahhotep is preoccupied with how to manage our interpersonal difficulties: in particular how to engage in disputes without leading to their escalation, and how to manage destructive anger.

But Ptahhotep’s recommendations are also rooted in a keen awareness of how flawed our knowledge of others is. This is a consequence of the fact that none of us ever attain full competence in any domain. Ptahhotep takes as an example somebody who is childless. In Ancient Egypt, it was important to have descendants. But Ptahhotep reminds his readers, ‘it is common that a father may be in misery, / And as for a mother who has given birth, another may be happier than she.’

Our judgements about others, and how well or badly their lives are going, may be wide of the mark. And we are wrong precisely because of the things we think we know about the world, or because we assume that we have expertise that we do not have.

The long search for wisdom

Ptahhotep’s Maxims remind us that the long search for wisdom reaches back far into our shared past. And the fact that one of humanity’s first named philosophers was from Africa offers a challenge to ethnocentric notions that restrict the practice of philosophy to only a few cultures: because, as Ptahhotep tells us, the emeralds of wisdom can be found everywhere.

Further Reading

Books

Norman Cohn’s discussion of Ma’at can be found in his book Cosmos, Chaos, and the World to Come (Yale University Press 1993)

There’s a beautifully clear translation of the Maxims of Ptahhotep in Literature of Ancient Egypt: An Anthology, __ edited by William Kelly Simpson (Yale University Press 2003)

Online Resources

You can read extracts from the Maxims on the UCL website.

For a more meaty philosophical discussion of Ptahhotep, see this paper by Joan Mulholland, exploring the Maxims through conversation analysis.