Understanding the world

The story of philosophy is the story of human attempts to understand the world of which we are a part, and to understand ourselves. But traditions of academic philosophy have tended to give greater weight to only a small handful of traditions — for example, Greek and European philosophy, Indian philosophy or Chinese philosophy.

But if philosophy is really about human attempts to understand the world, and to understand what it means to be human, then if we limit ourselves to a few traditions, we risk missing out on rich resources. As the African philosopher, Ptahhotep, wrote almost four and a half thousand years ago, the emeralds of wisdom can be found everywhere.

So recently, philosophers have started to ask about traditions of philosophy from other parts of the globe: traditions that may be just as subtle and as rich as the ones that are traditionally taught in philosophy courses. And one such set of traditions is that of Maya philosophy.

Philosophy

Reconstructing Maya philosophy

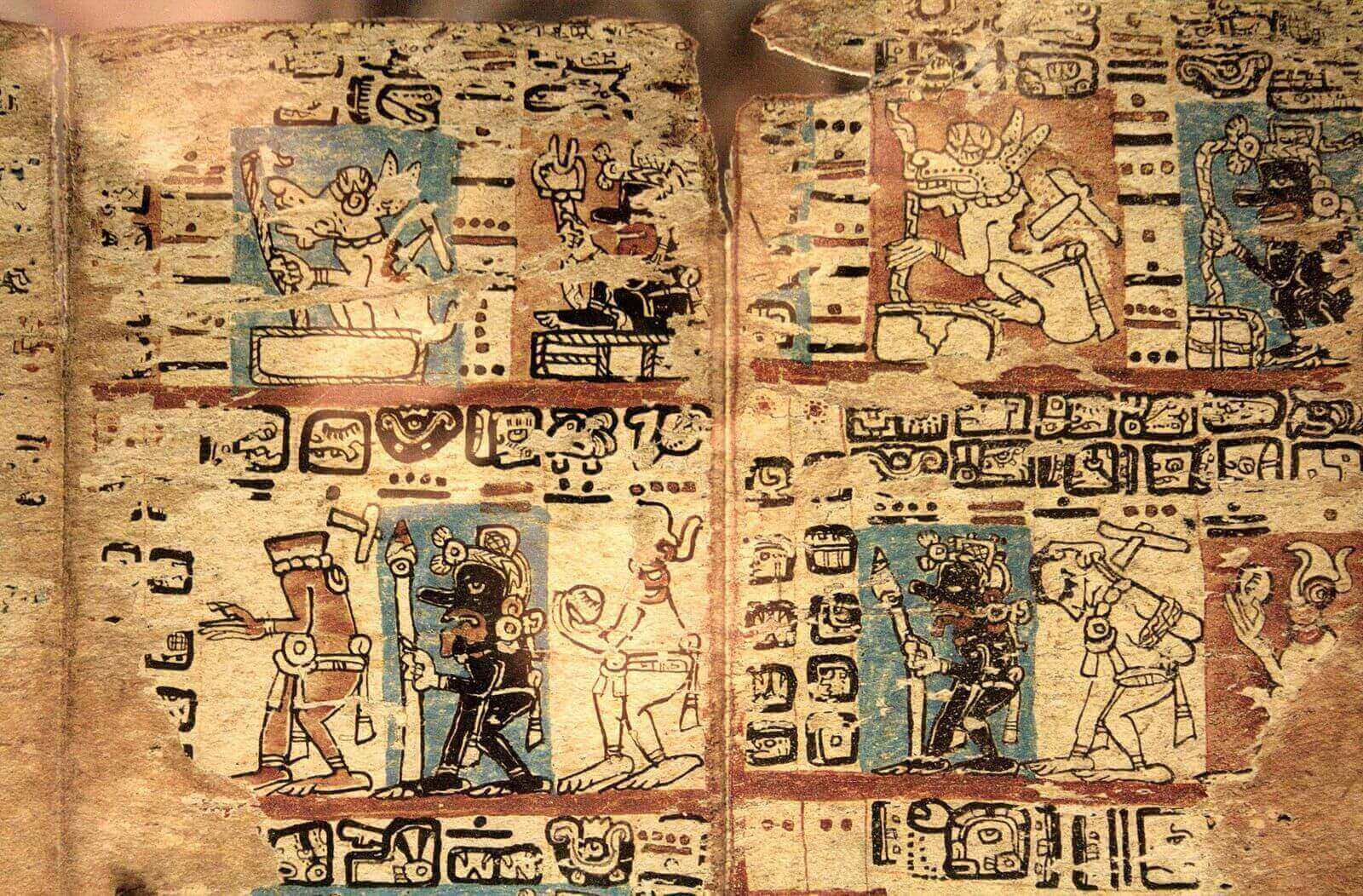

In his book on Maya philosophy, Alexus McLeod writes that “Mesoamerican thought […] has been uniquely neglected by philosophers” (p. xx). One reason for this is the patchiness of the textual tradition. European colonialism was ruinous for Maya culture, and thus for the continuity of the Maya philosophical tradition. Consequently, many texts from the pre-Colombian era have not survived, or have survived only in fragmentary form.

Scholars usually divide Maya history into three eras. The Preclassic era extends from the second millennium BCE to the first stone inscriptions that appear around 250 CE. During this period, there was a slow growth of urbanization, and a corresponding rise in social and bureaucratic complexity. The Classic era runs from 250 to 900 CE, and marks the height of the southern Maya highland city-states. And then the Postclassic era—when the centre of power shifts north to the Yucatán—runs from 900 CE to the beginnings of the Spanish colonial era. The printed texts we do have come from the Postclassic era and after (although there are stone inscriptions and carvings from the earlier Classic era).

But there’s no reason that this patchiness of the textual record should hold us back from taking Maya thought seriously and working hard to reconstruct it. We know about the Presocratic philosophers of the Greek world—people like Thales, Anaxagoras Pythagoras—based on fragments and reconstructions, rather than on complete texts. And if we still take these thinkers seriously as philosophers, there’s no reason not to do the same with Maya thought.

The trouble with time

All philosophical traditions have their own distinctive preoccupations: and if there is one central preoccupation in Maya philosophy, this preoccupation is time.

Within Maya philosophy, time is central to any understanding of the world and to ourselves. For the Maya philosophers, time is not just the element we swim in. It is not just something to which we are subject. Instead, the Maya maintain that human activity actively fashions time. And in fashioning time, we help to fashion existence as a whole.

According to the Maya understanding of time, creation is not a one-time thing. Instead, it is an ongoing process in which we participate by giving shape to time. This is illustrated beautifully by the Popol Vuh, probably the most famous of all Maya texts.

The Popul Vuh is a mythological and philosophical text of the Kʼicheʼ people first written down in the middle of the 16th century. At the beginning of the book, the gods are struggling to create human beings. They make several attempts. First they create animals and birds, but these creatures are incapable of speech. Then they make creatures out of mud, but they dissolve when they are wet. Next, they fashion effigies made of wood. By now, they are having some limited success. The creatures they make certainly look like people and speak like people. Like people, they are even capable of reproducing. But, the Popol Vuh says, these creatures continue to disappoint their creators. They are brittle and rigid. They have no sense of purpose and, crucially, they are incapable of “keeping the days.” Incapable of actively fashioning time, these proto-humans are incapable of participating in the ongoing processes of creation.

So the gods get rid of these botched humans and try for a fourth time, fashioning their new creations out of maize. And at last, the gods hit it lucky. These new human beings can speak and reproduce, but they can also give shape to time. And in ordering time, they can participate in creating and recreating the world to which they belong.

Ordering time

But what does it mean to give shape to time? In the traditions of Maya thought, this ongoing creation is referred to as tz’ak, or “ordering.” Human activity puts the world, and time, in order. Without this process of human ordering, the universe would remain in a state of chaos.

For the Maya, the keeping of calendars is essential to this ordering, and thus to giving shape to our collective lives. McLeod makes an analogy with our present-day ordering of time:

We can think of this in terms of the way that companies, for example, define their “calendric” systems. In making Monday to Friday 9am–5pm, with a 12–1pm lunch break, for example, the standard business schedule, companies we work for order our experiences and create the boundaries within which we live and must think of our own lives and experience. 9 to 5 on the weekdays becomes “work time,” distinct from the “rest time” after 5, or the “enjoyment time” on the weekend.Philosophy of the Ancient Maya (pp. 25-6)

This ordering of time is not just personal. It is also collective and political. The ruler orders the city-state through shaping how time is ordered within the state, and through shaping how time is experienced. And one way that this happens is through ritual.

Ritual and the shaping of time

Think of an ordinary everyday ritual, like making a cup of tea the same way each morning, and drinking it in bed. This ritual gives rise to a very specific sense of time. If you repeat this ritual every day (and if you don’t, you should), you soon find that the ritual seems to gather together your mornings so that experientially, every morning is closely bound with every other. Yesterday morning, this morning and tomorrow morning feel like they are part of a single time. In a real, experiential sense, as you sit in bed drinking tea, this morning, tomorrow morning and yesterday morning feel experientially closer than the meeting you have at 11am, or the errands you have to run before you get to the meeting (and this is what can make the experience of drinking tea in bed so deliciously timeless).

Even the simplest of rituals shapes our overall sense of time like this. Ritual gives time a particular, specific quality and rhythm, and thus it shapes the pattern of our lives. You could see human existence as a patchwork of different, overlapping experiences of time, shaped by the rituals in which we engage, individually and collectively.

When you start to see how even the smallest rituals play a role in giving shape to our sense of time, you can begin to see the force of the broader Maya philosophical claim that ritual is one of the primary ways of ordering time, and thus one of the ways that human beings give order to the universe. As McLeod puts it:

The ritual actions of humans play a role in the continual creation of the cosmos. The gods create the patterns and the original stuff of the world, which is then molded, manifested, and sustained by humanity Philosophy of the Ancient Maya (p. 31)

This is one reason that Maya philosophy is compelling, and can still speak to us today. It tells us that the world we inherit is only partially formed, that it is a creation still in progress. And it tells us that it is up to us to take this raw material, and through our own rituals, to continually reshape it, so we can work continually on creating the world afresh.

Further Reading

Books

The field of Maya philosophy is still very young. For this Philosopher File, I have relied mainly on Alexus McLeod’s work: both his brilliant Philosophy of the Ancient Maya: Lords of Time (Lexington Books 2018).

Online Resources

Read the Looking for Wisdom interview with Alexus here.

There’s a great podcast with Alexus McLeod on New Books in Philosophy.

This essay on the APA blog on the Mesoamerican philosophy renaissance is really worth reading.

And there’s an excellent primer on Maya philosophy here.

Image: From the Madrid Codex. By Michel Wal. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Via Wikimedia Commons.