Love, Strife and The Mad Machinery of War

In his great poem, On the Nature of the Universe (De Rerum Natura), Roman poet-philosopher Lucretius (born c. 100 BCE) asks what it means to live fully in a world where everything is always in motion. A follower of the Greek philosopher Epicurus, Lucretius proposed that the universe was both dynamic and unstable. But as well as setting out a vision of physics, or how the world is, Lucretius also set out a compelling vision of what it means to live in such a world.

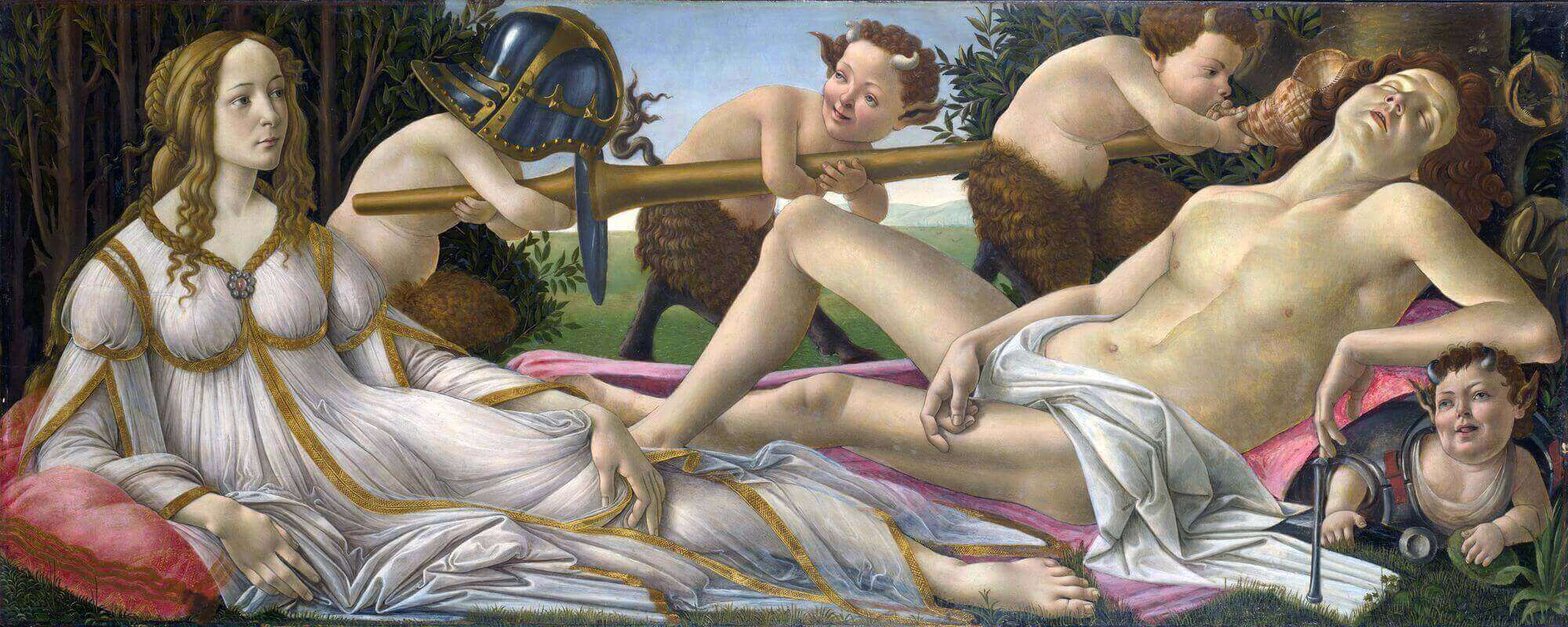

Ethics appears right at the beginning of On the Nature of the Universe, when Lucretius sings the praises of the goddess Venus. He conjures up the image of the struggle between Venus and Mars, between love and strife. Lucretius offers up a prayer to the Goddess (in the brilliant translation by Alicia Stallings) as follows:

Both on dry land and on the deep, Make the mad machinery of war drift off to sleep. For only you can favour mortal men with peace, since Mars, Mighty in Arms, who oversees the wicked works of wars, Conquered by Love’s everlasting wound, so often lies Upon your lap, and gazing upwards, feasts his greedy eyes On love, his mouth agape at you, Famed Goddess, as he tips Back his shapely neck, his breath hovering at your lips.\

(Book I: 37)

This theme of the struggle between love and strife goes back to the philosopher Empedocles, for whom the universe could be seen as existing in a constant dialogue between forces of attraction and repulsion, between binding together and severing apart.

Lucretius’s initial invocation of this struggle between love and strife is not just a bit of fancy literary footwork. It also goes to the heart of his atomist view of the world: atoms combine into bigger bodies, and these bodies break apart. All things come into existence and crumble away again through the combination, recombination and eventual separation of atoms.

Both of these things — love and strife, combination and separation — are necessary to existence. If things just clumped into larger and larger entities, then the universe would simply collapse together into a single, undifferentiated mass. But if they didn’t combine at all, nothing would happen, there would be no universe at all. So for Lucretius, both these processes are necessary: uniting and severing, coming together and breaking apart, Venus and Mars.

But for Lucretius, what is crucial is the question of who has the upper hand. If we focus on division, on severing, on separating out, then the mad machinery of war clanks into action, and we will never know peace. But if we allow our divisiveness to relax a little, and see the opportunities that Venus offers — the fact that the world always offers new creations, new possibilities — then there is the prospect of a more peaceful existence.

Cutting Loose from Religion

For Lucretius — as for his inspiration, Epicurus — there is a direct line from his physics of atoms and void to his view of ethics. Lucretius claims that the world is an inherently turbulent place. It is perpetually in motion, always unstable, liable to change at any time. But our ethical codes are often inadequate when it comes to responding to living in this changeable world.

Here, Lucretius — the same Lucretius who begins by evoking Venus and Mars — singles out religion as a particularly ineffective way of responding to the mutability of the world. Religion, he says bluntly, “breeds wickedness” (Book I: 80). Through religion, we conjure up ideas of virtue and vice, and we live in accord with these ideas: but these abstractions can lead us to terrible acts.

For evidence, Lucretius cites the case of Iphigenia, the daughter of Agamemnon, who is sacrificed by her father so that the Greeks can have favourable winds to speed their ships towards Troy. Here is the way Lucretius tells the story:

As soon as they bound the fillet round her hair

So that its ends streamed down her cheeks, the girl became aware

That waiting at the temple for her there would be no groom –

Instead she saw her father with a countenance of gloom

Attended by the priests who kept the blade well hid. The sight

Of people shedding tears to see her froze her tongue with fright.

She sank to the ground upon her knees. It did not mean a thing

For the princess now, that she had been the first to give the king

The name of Father. No, for shaking, the poor girl was carried

By the hands of men up to the altar, not that she be married

With solemn ceremony, to the accompanying strain

Of loud-sung bridal hymns, but as a maiden, pure of stain,

To be impurely slaughtered, at the age when she should wed,

Sorrowful sacrifice slain at her father’s hand instead.

All this for fair and favourable winds to sail the fleet along! –

So potent was Religion in persuading to do wrong.\(Book I: 85-101)

For Lucretius, this is an example of how — if we ignore the world, and turn to abstractions for ethical guidance — we risk ending up doing terrible things. So part of the task Lucretius sets himself is that of freeing us from the “tight strictures of religion” (Book I: 930), and he wants us to look in a different direction for our ideas of ethics.

Tracing the Flights of the Swallow: From Physics to Ethics

So Lucretius sets about rebuilding an ethics that is an adequate response to the fact that we live in a world in motion. Through doing this, he hopes, it might be possible to find a way to live well among this great hubbub of love and strife. Or, even more precisely, it might be possible to find a way to move well through this great hubbub.

In some ways Lucretius is a faithful follower of Epicurus: he takes on board Epicurus’s physics of atoms and void, his critique of religion, and his ideas about the harms caused by our fear of death. But in other ways, he departs from Epicurus’s teachings. Lucretius is a much more dynamic thinker than Epicurus. the Epicurean ideal of ataraxia is of a kind of stillness, but Lucretius seeks instead something like an ideal kind of motion.

At one point in his poem, Lucretius compares Epicurus to a swan, and himself to a swallow. This may seem like a nice piece of self-deprecation. Swallows were associated in the ancient world with prophecy. They were representations of rebirth, of desire, and of spring. They were associated with Venus. So Lucretius’s identification with the swallow isn’t quite so humble as it might first seem. But there is something else going on as well. In the last piece on Lucretius, we saw how the clinamen — the swerve of an atom, the deep-rooted unpredictability of things — is central to Lucretius’s physics. And there is no bird that swerves with as much panache as a swallow. In his book on Lucretius’s ethics, Thomas Nail writes about how the image of the swallow fits Lucretius’s physics of swerving atoms perfectly:

Swallows are known above all for their chaotic and unpredictable flight paths as they hunt insects in mid-air. Swallows spiral, circle, dive, and make sharp turns and twists that few other birds can manage. Since humans cannot see these insects, it looks as though the swallows are moving ‘randomly’, when in fact their erratic-looking movements are the result of a highly relational and responsive entanglement with their prey. (p.22)

Lucretius’s ethics is a sensual, embodied ethics of movement. And it is hard to imagine a more beautiful image of what it might be to move, to swoop — with skill and suppleness — through this turbulent world.

Movement and Oppression

For Lucretius, then, ethics, is about what we do and how we move. Ethics is something to be lived as an embodied being, rather than something to be simply theorised.

But what, more precisely, makes an action ethical for Lucretius? One answer is that unethical action is action that works against this ability to move, that involves the stopping up of life, or risks falling into a kind of stasis that makes everything rigid, and renders us unresponsive to the world, to each other, and to what our own bodies are telling us.

And here, Lucretius makes the startling claim that power is one of the main ways that life can be stopped up. Although power can often seem to offer us more possibilities for movement, as often as not, it simply calcifies us. It makes us less supple and rigid, and risks bringing both ourselves, and those over whom we wield this power, closer to death. Here is what Lucretius writes:

Take Avarice and the blind drive of Ambition:both may draw

Wretched men to step outside the limits of the law –

Often even as partners and accomplices in crime –

As each man, day and night, strives harder than the next to climb

Atop the pyramid of power. It is largely the dread

Of death on which these open wounds of life thrive and are fed,

For Vile Disgrace and Bitter Want seem so far from the state

Of a sweet, established life, they almost loiter at Death’s gate. (Book III: 59-65)

Power is a kind of death. It removes our ability — and removes the ability of others — to move freely, in response to this changing world.

Take many of the ethical issues that face us, and you can see what is at stake is this stopping-up of movement, this calcification. Why are things as diverse as slavery, poverty, oppression, and battery farming bad? The Lucretian answer to this question is that these are all ways in which the swoop and surge of life is restricted. They are all ways of stopping-up our natural power of movement, imposing restrictions on the fullness of life. They are all things that stand in the way of the responsive, relational entanglement with the world that is the sign of a life in motion, and the hallmark of a life fully lived.

Further Reading

All the quotes from Lucretius come from Alicia Stallings’ translation, Lucretius: The Nature of Things (Penguin 2007). I’ve used the EPUB version, so referenced the line numbers in the text.

Two books that are really worth reading are Thomas Nail’s Lucretius II: An Ethics of Motion (Edinburgh University Press 2020), and Michel Serres’s The Birth of Physics translated by David Webb and William Ross (Rowman & Littlefield 2018). My own take on Lucretius here comes from both these works.