Love, we are told, lifts us up where we belong: “Where the eagles cry / On a mountain high… / Far from the world we know / Where the clear winds blow.”

When we are in love, the world takes on a different, more giddying perspective. But shifts in perspective are tricky things. When we are loved-up and out of our right minds, are we at last seeing the world clearly? Or have we descended into a kind of madness?

In this week’s article, we’re going to be exploring love, transcendence, and madness in Plato’s dialogues. We’re going to see what the priestess and philosopher Diotima has to say about the transcendent path of love in Plato’s Symposium. And we’re going to see how in the Phaedrus, Socrates argues that love sends us mad—while also making the case that sometimes a spot of madness is just what we need.

But we’re going to start with the experience of finding ourselves suddenly smitten, caught somewhere between madness and transcendence, just when we least expect it.

Smitten kittens

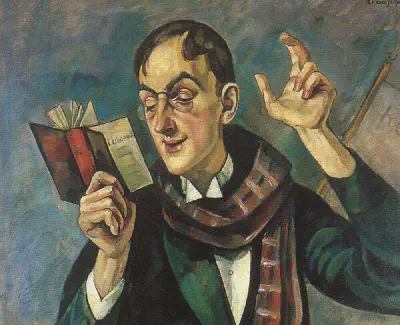

You don’t know how it happens. You can’t predict when it will happen. Nevertheless, it happens. One day, you run into somebody new, or you find yourself unexpectedly seeing somebody you already know in a different light. And you are utterly smitten. You are spellbound, enchanted, barely able to breathe or to speak.

Sometimes philosophers refer to this as “limerence”, a term first coined by the psychiatrist Dorothy Tennov in the late 1970s. Tennov invented the word to refer to the strange infatuation with another person that bursts upon you for no obvious reason. In an interview in the UK Observer in 1977, Tennov said,

I first used the term ‘amorance’ then changed it back to ‘limerence’… It has no roots whatsoever. It looks nice. It works well in French. Take it from me it has no etymology whatsoever.[1]

It looks good. It feels right. It works well in French. And it has no roots in the real world. For all these reasons, “limerence” sounds like a well-coined term for romantic infatuation.

In her 1979 book Love and Limerence: The Experience of Being in Love, Tennov writes that when you are in a state of limerence, you can think of nothing but the object of your desires. You cannot sleep. You lose your appetite. The object of your desires takes on a transcendent glow. And what you long for most is that your obsession should be reciprocated.

However, there is something problematic with limerence. The single-minded focus of limerent obsession is potentially destructive: both for the one who is so obsessed, and for the object of their obsession. What if the other person has no interest in reciprocation? What if this limerent experience is used to justify (as it often is) all manner of crazy, creepy, stalky, destructive behaviours? Maybe limerence should be seen as a condition, a sickness (and, indeed, there is even a Reddit community dedicated to supporting those “who self-identify as being in the state of limerence and are looking for support and strategies to deal with their condition.”)

Love’s upward trajectory?

But, if Plato is to be believed, limerence may also be a doorway to a different way of seeing the world. In the Symposium, Socrates relates the story of how Diotima taught him that infatuation can be the first step on a path to transcendence.

Diotima’s theory of love, as it appears in the Symposium, functions like a staircase or a ladder (it is often referred to as the “ladder of love”). Love is a process of ascent, with each stage providing a broader, more expansive view of love—and of reality itself—than the one before.

Diotima argues that love begins in an infatuation with the body of a single individual. This infatuation “begets beautiful ideas”—which seems like a nice description of the way our minds can be filled with dreamy notions about the object of our desires.

But the path of love only begins here: this is not where it ends. The next stage comes about when the lover realises the same beauty that inspires their infatuation lies not just in their beloved, but in others as well. After all, Diotima cautions, we would “be very foolish not to think that the beauty of all bodies is one and the same.” Here, the lover loosens their obsessive focus on one particular individual, to see that all others are potential objects of love (or of limerence). And when they see this, it becomes apparent that the desire they have for any single individual is a limited, cramped thing. This more general understanding of desire removes the lover from their fixation on a single object. And it reminds them that even though every other individual is unique and singular, this uniqueness and singularity are not in short supply. Singularity is everywhere. Everyone is unique, even if they are not uniquely so.

The next stage is when the lover recognises that beauty lies not just in bodies but in souls too. What we are attracted to, in the end, is not just a set of physical attributes, but a person.

And then, taking a further step up the staircase or the ladder, we go from recognising the beauty of persons to perceiving the beauty of the things these persons together fashion: human activities, institutions and cultures. Because if we are in touch with beauty, and if we value beauty, then together we can build beautiful things.

After this, Diotima says, the lover comes to recognise the beauty of the learning and knowledge that these cultures and institutions sustain. By now, Diotima says, “the lover is turned to the great sea of beauty, and, gazing upon this, they give birth to many gloriously beautiful ideas and theories, in unstinting love of wisdom.”

But there’s one final stage to this path. The culmination of the path of love is not just in the love of wisdom, or philosophy. Instead, it is in the love of beauty and of love itself. This is how Socrates summarises the argument.

This is what it is to go aright, or be led by another, into the mystery of Love: one goes always upwards for the sake of this Beauty, starting out from beautiful things and using them like rising stairs: from one body to two and from two to all beautiful bodies, then from beautiful bodies to beautiful customs, and from customs to learning beautiful things, and from these lessons he arrives in the end at this lesson, which is learning of this very Beauty, so that in the end he comes to know just what it is to be beautiful…

So what starts with our infatuation with one individual other leads us step-wise, Diotima argues, towards true knowledge and towards the love of love. This makes the path of love a complete religious and philosophical path, starting in limerence, and ending in transcendent experience .

Madly in love?

But if love takes us above or beyond our right minds, then there’s another question we need to ask: is this really such a good thing? After all, Tennov writes that limerence is “clearly a madness.” And Plato and Socrates knew this too. The long sufferings of the Trojan war began with the limerent desires of Paris and Helen. It is no accident that at the opening of Plato’s Phaedrus, his dialogue on love and madness, Socrates makes a passing reference to Homer’s story.

But if love is a kind of madness, in the Phaedrus Socrates wants to make the case that sometimes “the madness of love” is something we should actively seek. Ultimately, Socrates argues, madness can do more for us than “right-minded reason.” And the “divine madness” that is sent by the gods can be humanly and philosophically fruitful. God-sent madness, Socrates says, is better than human self-control.

Socrates gives four reasons that the madness of love can be beneficial. The first is that there is a connection between madness and prophecy. Socrates uses an etymological argument to talk about the closeness of the word manic or “mad” and the word mantic, or “prophetic” (as in “pyromancy”, meaning divination by fire, or “oneiromancy”, meaning divination by dreams). In the madness of love, we can have more profound insights into the world, just as the oracles of the ancient world, taken by divine madness, spoke prophecies and insights.

The second fruit of love’s madness, Socrates says, is that it is purificatory. In particular, it has the power to purge us of deep, ancestral guilt. In the wild, purificatory frenzy of madness, we are liberated from the rigorous logic of retribution and responsibility. And we become free.

The third fruit of madness is that it gives rise to creativity. We all know, after all, that the love-sick can turn to poetry (often, it has to be said, bad poetry) to try to make sense of their sickness. So the madness of love can provoke us to create new things, in a “frenzy of songs and poetry that glorifies the achievements of the past and teaches them to future generations.”

And the final fruit of madness, Socrates says, is the madness of transcendence. The lover is driven to a transcendent view that put them beyond the world, removed from the everyday logic of the world, soaring towards the realms of pure beauty:

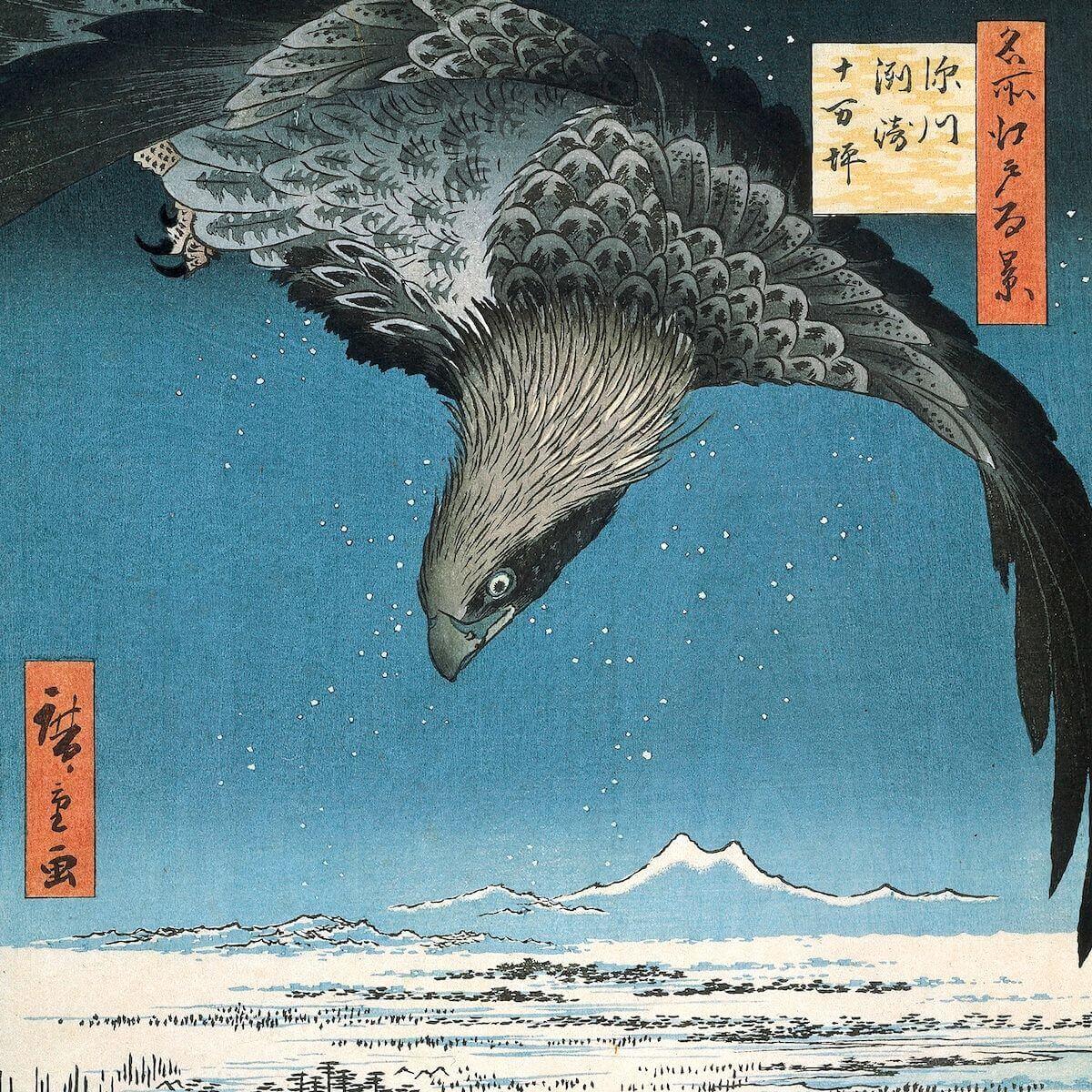

Now this takes me to the whole point of my discussion of the fourth kind of madness—that which someone shows when he sees the beauty we have down here and is reminded of true beauty; then he takes wing and flutters in his eagerness to rise up, but is unable to do so; and he gazes aloft, like a bird, paying no attention to what is down below…

But in his description of this final kind of madness, Socrates sounds a note of caution. Because for Socrates, love doesn’t lift us up where we belong. Or at least, not quite. It provokes the desire for true beauty—the end of Diotima’s quest. It sets our eyes on the heavens. It removes us from our concerns with what is “down below.” But as we take wing, our hearts all aflutter in our eagerness to rise beyond the everyday world, we are unable to fully attain the beauty for which we yearn.

And this is perhaps why, when a friend falls hard in love, you find them sitting by the window, staring dreamily out at the sky—as if they’ve forgotten the world of which they are still, nevertheless, a part.

Questions

Here are some questions to get you thinking about this week’s lesson. So dive into the comments on the Agora, and let’s chat.

- Have you ever experienced limerence? What is this experience like? And what does it tell us about human love and desire?

- How plausible is Diotima’s account of love’s upward ascent?

- The story of Diotima’s ladder puts a strong focus on the idea of beauty as something that is powerfully transformative. Do you think that recognising beauty—in others, even in cultures and in institutions—can be transformative in this way?

- Socrates gives four different arguments in favour of madness. In what ways, if any, can madness (or an absence of reason) be beneficial?

- In Socrates’s account of the madness of love, he doesn’t dwell on the potentially destructive effects of this madness (although he does reference the Trojan war in passing). Do you think the destructive effects of “being out of your right mind” with love outweigh the benefits? And if so, what is the best remedy for this madness?

Notes

[1] The Observer, 11 Sept 1977. See the blog post here.

[2] All references are from Symposium 210-212. See John M. Cooper (editor), Plato: Complete Works (Hackett 1997), p. 492-3.

[3] All references are from Phaedrus 241-245. See John M. Cooper (editor), Plato: Complete Works (Hackett 1997), p. 519-23.

More further reading

Books, articles, and music

Dorothy Tennov, Love and Limerence: The Experience of Being in Love (Stein and Day, 1979).

You’ve probably heard enough of the Joe Cocker and Jennifer Warnes version of Up Where We Belong. So how about Buffy Sainte-Marie’s version instead? Listen where.

Online resources

There’s a fascinating article on Quartz asking what if the purpose of falling in love (and of limerence) is not to get us into relationships, but instead to get us out of them. Read the link here.

For Diotima, love occupies a place between the everyday and the divine. The philosopher file on Diotima is worth reading in connection with the final ideas on transcendence that cannot be entirely fulfilled.