Social primates

Whatever else it might be about, love is about connection. It is about how we relate to each other. It is about how we feel about others, how we think about them, how we connect with them, what we do with them. Love is not so much personal as interpersonal.

So one way to make inroads into thinking about love is by thinking about what it means to be live alongside others. One of the fundamental questions for human life is this: how can we live well with our fellow human beings—and with the other beings (animals, gods, spirits, strangers, the dead and so on) with whom we share our lives and our worlds?

At root, we are social primates. We like play and mutual grooming and sex. We make friends and alliances. We fall out and make amends. We manage the competing demands of living out the lives we want, and living alongside the others on whom we depend. We snuggle and cuddle, struggle and quarrel. And through all this, we try to live as best we can.

It’s a complicated business being a social primate. There’s a lot to think about, a lot to process. And the question any self-aware primate one day has to ask themselves is this: How do you best manage all of this complexity?

Throughout history, human beings have conjured wildly diverse ways of answering this question, and managing all the complex dynamics of living in society.

Convivial communities

When seen in the context of our evolutionary heritage, it is not surprising the philosophy of love is so very complex. We saw in the previous article how love involves both ancient biological machinery and the various roles we assume within the society of which we are a part. But the biological machinery of love is not just about the mechanics of our individual bodies, or about our individual desires. It is also interpersonal. Our biology makes us social.

But what does it mean to be a social animal? One way of asking this question would be by asking “what is society?” But the idea of “society” can seem rather abstract. We imagine society as something out there, a coolly rational public realm at odds with the hot and messy private world of our domestic sphere. This can open up a rift between the question of how to live in society, and the more intimate questions and issues we face in our everyday lives: the poking and prodding and tickling and cuddling and annoying and soothing and arguing and gossiping and loving and hating.

So in this piece, we’re going to think instead in terms of community, and we’re going to be asking what makes a human community convivial. I’m taking this idea of conviviality from the work of two anthropologists, Joanna Overing and Alan Passes. In their edited collection of essays The Anthropology of Love and Anger: The Aesthetics of Conviviality in Native Amazonia, Overing and Passes use the idea of conviviality as a way of exploring what they call the “aesthetics of community.” [1]

In everyday use, “conviviality” might conjure images of living it up, or feasting and carousing. But conviviality goes beyond this. It may of course involve feasts and carouses (who doesn’t like the odd feast, or the occasional carouse?), but at the heart of conviviality is the question of what it means to live together (con-vivere). It is about how our communal relationships with each other quiver with life and feeling: with desire, with hope, with difficulty, with love and sometimes with hate.

All about communities

Philosophical accounts of love often overlook the importance of community and conviviality. In her book All About Love, writer and activist bell hooks complains that contemporary talk about love is often focussed on individuals, couples and nuclear families:

Communities sustain life—not nuclear families, or the “couple,” and certainly not the rugged individualist. There is no better place to learn the art of loving than in community.[2]

As a starting point for thinking about love, the idea of community has one significant advantage over the idea of the nuclear family, the couple, or the individual. The advantage is that community is a human universal. The fact that we are social communal beings is baked into our biological machinery. Of course, in different societies and cultures we organise our communities in different ways. Some of us live in nuclear families, some of us in more sprawling networks of kinship. Some of us live out our lives as a part of romantic relationships, while others embrace more anarchic structures. But these social and cultural forms are secondary to the fact that we are in community with each other.

It’s for this reason that I want to start by thinking through the philosophy of love on the basis of community. Our current day notions of the romantic couple and the nuclear family are relatively localised. Not all societies organise themselves in this way. But all human beings everywhere have a concern with what it means to be a sociable, convivial creature, living in society with others.

So if we think about love on the basis of community, we don’t need to commit ourselves to any one social structure. We don’t need to adjudicate on whether the nuclear family is beneficial or whether it is (as bell hooks herself argues) harmful; and the same goes for romantic relationships. Instead, we can sidestep these questions, and get started by thinking about what it means to live with others, convivially, with all the complexity this involves.

Love in the Amazon

The Enxet people of Paraguay provide a compelling account of what it is to be a social being, and how we navigate the challenges of living and loving within a community. Plunging into Enxet philosophy may seem a strange approach to talking about the philosophy of love. Most philosophical accounts of love start out with Plato, and take it from there. But taking a view from elsewhere can help shake up our thinking, and undermine some of our assumptions. So let’s see if we can sketch out an Enxet theory of love.

According to the anthropologist Stephen W. Kidd, for the Enxet, the centre of our personhood is found in the wáxok, which is located in the stomach. This may sound exotic, but we too talk about how our identity lies in a physical organ: in the heart that hangs in our chest, or in our brain that nestles in our skull.

For the Enxet, emotions are physical changes in the wáxok (just as we might say “my heart is all aflutter”). When we are content, wáxok stretches out; when we are sad, it becomes heavy; when we are afraid, it shivers.

The wáxok is not just the seat of emotion. It is also the place where thinking and knowing take place. The Enxet say that the wáxok searches (for example, when you are trying to think of something). It mentions things (when an idea comes to you). It makes fun of things (when you have a rising sense, somewhere in your stomach, that you want to make a joke). The wáxok even turns around and goes back to where it came from (when you change your mind).[3]

The wáxok is also inherently social. It is at the same time personal and interpersonal, and there is no hard boundary between the two. This social wáxok is achieved as you grow from being a baby to a child to an adult. It takes shape through your engagements with others. And when your wáxok is well-formed, this gives you the ability to engage better with others on the basis of love and knowledge.

A fully formed adult, the Enxet say, is somebody whose wáxok is hápek, or soft. The word hápek can also be used to a semi-inflated football, or a door that is unlocked and therefore easy to open. The ideal way of being is to have a slightly deflated self—a hápek wáxok. This makes you open to others. It allows you to be affected by the sufferings of others, good at spending time with them—sharing with them, eating and drinking together.[4] The person with a good wáxok is knowledgable about love.

An Enxet theory of love

This talk about the wáxok may seem unfamiliar. It is not, after all, a term you usually find in philosophy textbooks. But it gives us an alternative way in to thinking about the philosophy of love. If we take an Enxet perspective on love, there are several things we can say about what love is:

- Love is rooted in our physical, embodied being: in our gut, where our wáxok resides.

- Love involves our bodies, our emotions, and our thinking (because the wáxok is where thinking and feeling happen as well).

- Love is about our built-in sociality: it is both innate and also learned through our relationships with others.

- And finally—perhaps most importantly—our capacity to love is rooted in our susceptibility to others and the extent to which we can be affected by them. Love needs softness. If we are over-inflated and hard, we cannot love, and we cannot live successfully in society with others.

This is beginning to look like a pretty well-formed theory of love.

The limits of conviviality: love in the city

The Enxet account of love is a persuasive starting point for a theory of love, one that does not commit us to any particular social structure. But there is a problem. The Enxet are—or at least were in the past—a small-scale, face-to-face society. Yet most of us do not live like this. For those of us who live in crowded towns and cities where we encounter thousands of others on a daily basis, it is not clear that we can (or even should) be this convivial. When we are so comprehensively outnumbered, how can we be soft—like semi-deflated footballs—with everyone we meet?

When we scale up our communities from the small scale to the large, new problems emerge when thinking about love. Love is complicated enough in the rainforests of the Amazon. But there’s a whole new level of complication if you find yourself in a city. The anthropologist Robin Dunbar famously argued we are evolved to keep track of more or less one hundred and fifty other individuals. These are the people “we know personally, whom we can trust, whom we feel some emotional affinity for.”[5]. And this limit of one hundred and fifty, give or take a few, is imposed by the size of our brains. Dunbar argues we simply don’t have the capacity to deal on this intimate face-to-face basis with the thousands with whom we share our lives.

We are creatures who were evolved to snuggle and struggle in relatively small social groups. But these days, more often than not, we find ourselves in communities not of tens or hundreds of others, but millions. So how, in these conditions, are we to go on loving and living? This is the question we’ll explore next week. We’ll be travelling from ancient Athens to the world of Classical Chinese thought to ask about the tension between partial love and impartial justice.

Questions

Here are some questions to get you thinking about this week’s article. Feel free to dive into the comments on the Agora, and let’s chat.

- Do you agree that the idea of community is overlooked in our contemporary views of love? What evidence is there for or against this claim?

- When I first read about the Enxet, I was fascinated by the idea that love involves your wáxok being slightly deflated and soft. What is the relation between love and softness? In what ways might softness be a good thing? And in what ways might it be a bad thing?

- In this week’s piece, I make the case that the Enxet idea of love could be seen as a genuine philosophy of love. Do you agree?

- In her book All About Love, bell hooks writes that “Communities sustain life—not nuclear families, or the ‘couple,’ and certainly not the rugged individualist.” Do you agree? Or are there many ways of sustaining life?

Notes

[1] Joanna Overing and Alan Passes (editors), The Anthropology of Love and Anger: the aesthetics of conviviality in Native Amazonia (Routledge 2000), p. xi.

[2] bell hooks, All About Love (William Morrow 2000), p. 51.

[3] Stephen W. Kidd, “Knowledge and the practice of love and hate among the Enxet of Paraguay”, in The Anthropology of Love and Anger: the aesthetics of conviviality in Native Amazonia, edited by Joanna Overing and Alan Passes (Routledge 2000), p. 115.

[4] ibid., p. 118.

[5] Robin Dunbar, How Many Friends Does One Person Need?: Dunbar’s number and other evolutionary quirks (Faber and Faber 2010), pp. 3-4.

More further reading

Books, articles and music

Try Ivan Illich, Tools for Conviviality (Marion Boyars 2001) for an interesting exploration of the idea of conviviality in relation to our contemporary technological society.

There’s not much written on Amazonian philosophy. The book by Overing and Passes is a great start, and full of rich ideas. Try also Cannibal Metaphysics by Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, with its radical agenda of decolonizing thought. (Univocal 2014).

And this week’s song is We All Stand Together by, er, Paul McCartney and the Frog Chorus. If you really must listen to it, then this is the link.

Online resources

The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy has an entry on ethnoepistemology that explores some interesting issues that touch on the ideas explored in today’s piece.

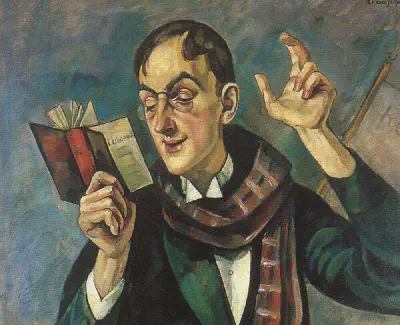

Image: Picknick by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner c. 1920. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.