Introduction

The Daodejing or Classic of Ways and Powers is one of the most translated of all Chinese texts. It is traditionally attributed to the Daoist sage Laozi (also written Lao Tzu),

At just over 5000 characters long, the Daodejing is a masterpiece of compression. But due to its brevity and its elliptical style, it has been read in a multitude of different ways: as everything from a mystical treatise to a hard-headed work about statecraft.

Life

But what about Laozi, the Daodejing’s purported author? The name “Laozi” literally means “Old Master.” The Chinese tradition says that Laozi’s given name was Li Er, and some accounts make him a contemporary of Confucius. However, over the last century scholars have increasingly cast doubt on the historicity of Li Er. And even if there was a historical individual called Li Er, his connection with the Daodejing is probably tenuous.

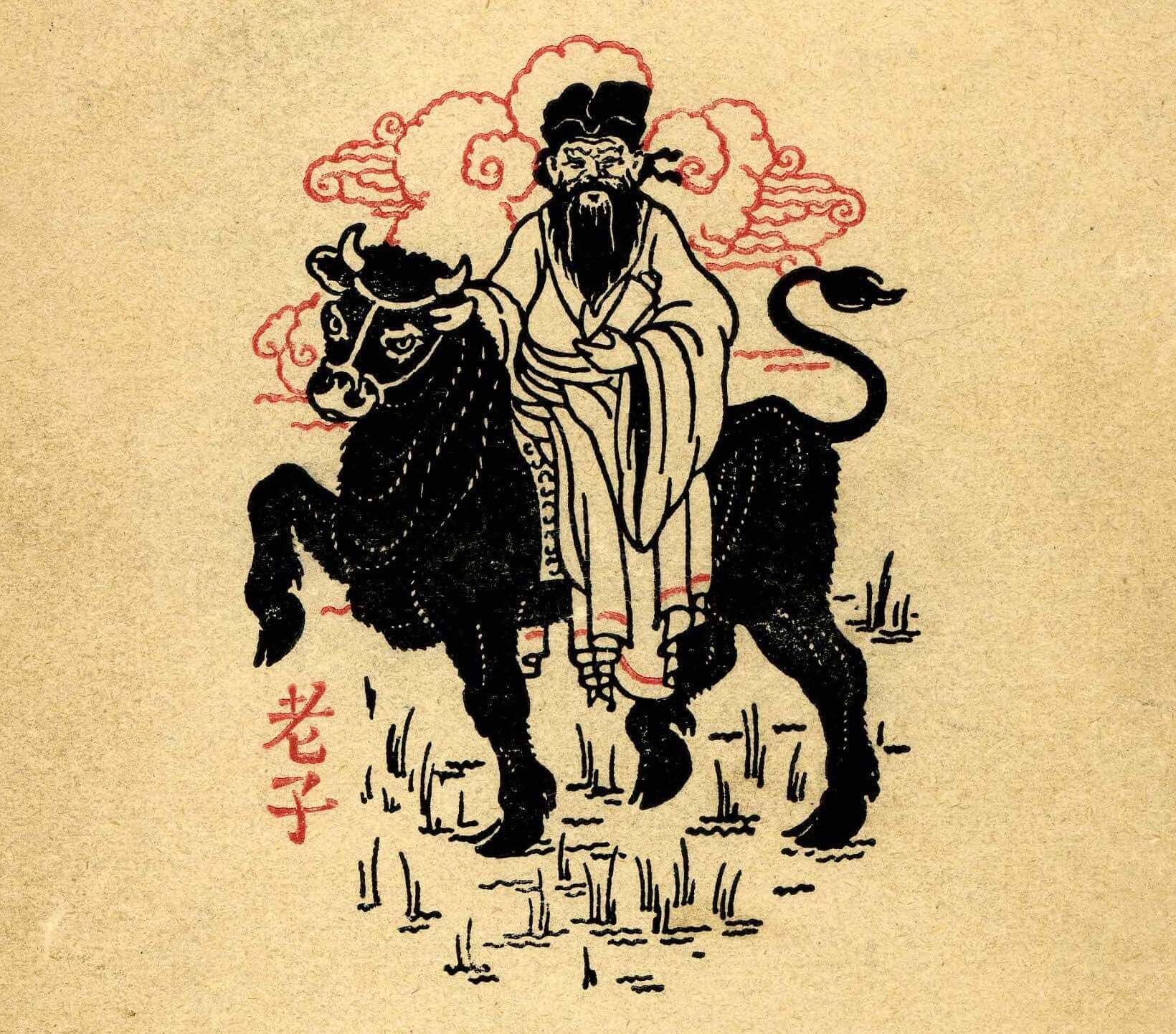

The sage and the ox

But as usual, where history remains silent, stories proliferate. The legendary accounts make Laozi a librarian in the court of Zhou. It was a role that gave him time to read the thoughts of the ancients, and thus to cultivate wisdom. The historian Sima Qian tells us Laozi eventually got sick of court life, and at the age of eighty headed west to the frontier regions to live as a hermit. At the frontier, a guard apprehended the philosopher, refusing to let him travel onwards until he had passed on his wisdom. So Laozi recited the Daodejing and the border-guard wrote it down. Then the Old Master continued on his way west, riding on the back of an ox, and he was lost to history.

Some accounts even go so far as to say that after heading west from China, Laozi ended up in India, where he became a teacher of the Buddha. Like everything else about Laozi’s “biography”, there is no evidence that any of this is true.

Philosophy: Dao and De

Ways and words

Laozi’s text, the Daodejing, explores two concepts in particular: dao and de (sometimes written tao and te). Both are tricky to translate, and both subject to considerable debate. The Daodejing begins with the famous sentence :

The dao that you can dao is not the constant dao.

The word dao in Chinese can mean both “way” or “path.” But it can also mean “to speak” or “to talk about.” So one common way of translating the opening sentence is to take the first and third dao as meaning “way” and the second as meaning “to talk about”:

The way you can talk about is not the constant way.

In this reading, the dao, the natural way of things, is something that escapes all our attempts to speak of it.

But there’s a problem here. When translating dao into English as “the” dao, we risk imagining that the dao is some kind of metaphysical entity: something big, important and deeply mysterious. However, the definite article does not exist in the original Chinese. So dao can mean the dao, or a dao, or even daos, in the plural. This means that you could also translate the first line as follows:

Ways you can talk about are not constant ways.

But there’s also another level of ambiguity as well, because it is possible to read the second dao not as “to say” or “to talk about”, but as a verb related to the noun “way” or “path.” Reading it like this, “to dao” would mean something like “to tread a path”, “to make your way”, or “to lead.” This would give us something like the following:

Ways you can tread are not constant ways.

If you read it like this, the text might be saying that the paths we take as we make our way through the world—the paths that remain open to us—are always subject to change. You can take a particular path today, but that same path may not be open tomorrow (this recalls Heraclitus’s claim that you can’t step into the same river twice). To keep on moving, if you are a skilful wayfarer, you need to be able to recognise the inconstancy of the paths you are on. You need to be vigilant. And you need to be flexible. Because if you rely on a pre-ordained and inflexible Way, you will almost certainly stumble.

Powers and potentials

The second concept in the Daodejing is de. In texts from the Confucian tradition, de is often translated as “virtue”; but when it comes to Daoist texts like the Daodejing, something like “potency” is closer to the mark. So you could read de as the potency or potential that a thing has by virtue of being the kind of thing that it is. The de of a fish is the potential it has to be a fish, to do fishy things. The de of a tree is the potential it has to exist—or even to flourish—as a tree. And so on.

The word de goes back to the Zhou dynasty where, according to the scholar Constance A. Cook, it referred to “a fluid inner force available only to those who participated in the ancestral worship system” (see reference below, p. 117). By the time the Daodejing was written, de had lost its connection with ancestor worship. But it maintained this sense of inner force and potency. So if we understand it like this, the aim of the Daodejing is to tell us how to tread paths through an inconstant world whilst protecting our potency and our force.

Unlike virtue, de is not something you practice. The moment you start thinking of de as something to be practised or something that you do, you lose sight of it. Instead, it is something that comes through allowing your potential to express itself through wuwei or non-action. Here’s how Edward Slingerland translates the passage in the Daodejing (translating de as “virtue”):

The highest Virtue [de] does not try to be virtuous, and so really possesses Virtue.The worst kind of Virtue never stops striving for Virtue, and so never achieves Virtue.The person of highest Virtue does not act [wu-wei] and does not reflect upon what he is doing.

For the Daodejing, the optimal way of being is allowing our de to fully express itself by refusing all kinds of forcing and striving. Only when we remove ourselves from striving can our de, or potency, be fulfilled. And then, full of life, we can continue on our own idiosyncratic way, making new pathways as we navigate our passage through the world.

Further Reading

Books

Lots of translations of the Daodejing are available. Try the ones by David Hinton or Philip Ivanhoe.

Constance A. Cook’s essay “Which Comes First? Dao 道 or De 德: Evidence from the Guodian Manuscripts” is in chapter six of Dao Companion to the Excavated Guodian Bamboo Manuscripts, ed. Shirley Chan (Springer 2019).

There’s a readable introduction to the Daodejing as a philosophical text by Hans-Georg Moeller called The Philosophy of the Daodejing (Columbia University Press 2006)

It’s really worth reading Edward Slingerland’s Trying Not to Try (Penguin 2015), which explores the idea of wuwei across the different traditions of ancient China, and puts it in the context of contemporary cognitive science.

Online Resources

For an accessible, free translation of the Daodejing with accompanying Chinese text, see the website run by A. Charles Muller.