The Many Voices of the Huainanzi

In the year 139 BCE, Liu An (劉安 179-122 BCE), the scholarly-minded King of Huainan, wanted to ingratiate himself to his cousin once removed, the Emperor Wu of Han. So he did what any self-respecting scholar king would do. Anxious to demonstrate his usefulness and his political nous, he convened a group of scholars to put together a text on the art of leadership to present to the young emperor. The resulting text, the Huainanzi, was an ambitious work: a compilation of everything a self-respecting ruler should know, a manual for running an effective state.

Liu An was not only the king of Huainan, but also a scholar in his own right who wrote poems, and treatises on topics as diverse as music, alchemy, and philosophy. And the Huainanzi reflects this breadth of interests. It covers a dizzying array of topics: from statecraft to military strategy; from metaphysics to the prediction of good and bad fortune; from the art of rhetoric to the challenges of ruling over an empire that encompasses a broad diversity of peoples and customs.

It is this diversity and range that make the Huainanzi so fascinating. It is more an anthology than a single-authored text, a text that not only was composed by many hands, but that contains many voices. Not only are the topics in the text astonishingly wide-ranging, but so are the philosophical sources on which the text draws. The Huainanzi ranges freely between Confucian, Daoist, and Legalist perspectives. It draws the Daodejing and the Zhuangzi, but also on the Book of Changes, the Spring and Autumn Annals, the philosophy of Mozi, the thought of Confucian thinkers including Mengzi and Xunzi, and the legalist thinker Hanfeizi. And all of this is by design. The postface to the text says that:

We have not followed a path made by a solitary footprint or adhered to instructions from a single perspective or allowed ourselves to be entrapped or fettered by things so that we would not advance or shift according to the age. [1]

As a ruler of a sprawling empire, what is more useful? A single perspective, a single theory of how to rule? Or something that can more closely reflect the chaotic diversity of your empire: a toolkit for handling diverse peoples, cultures, situations, and ideas? Single theories and single perspectives are fatally inflexible: they are not responsive to changing times and changing circumstances. So the Huainanzi presents itself as a set of ways of weaving all this complexity together to create an enduring political fabric.

We have created and composed these writings and discourses as a means to knot the net of the Way and its Potency, and weave the web of humankind and its affairs. [2]

Root and Branch

This might sound as if the Huainanzi is something of a ragbag, a text both incoherent and baggy. But this would be to misrepresent it. There is instead an ambitious attempt to structure all of this material into something that is both coherent and also hospitable to the sheer diversity of its sources. For all its breadth, the Huainanzi is very carefully constructed.

The first eight chapters set out the “roots” of an underlying theory that animates the text. These “roots” of ben (本) are: the “way” (dao 道), “potency” (de 德), “heaven” (tian 天), “earth” (di 地), “time” (shi 時), “resonance between things” (ganying 感應), humankind (ren 人) and morality (renyi 仁義). Taken together these roots set out a base-line philosophical stance from which everything in the text follows.

The chapters that follow then explore the “branches” (mo 末), the practical application of this base-line philosophical stance, exploring how these underlying principles play out in specific circumstances and how they can be applied to the bewildering diversity of human affairs (shi 事).

For the Huainanzi, to ignore underlying principles and think only about individual circumstances is to cut yourself off from understanding the deeper trends in how things unfold. But to ignore individual circumstances and think only in terms of underlying principles is to become blind to the changing conditions in which we all live. You need both: theory and practice, underlying principles and the way these principles structure uniquely unfolding sets of conditions.

Thus, numerous are the words we have composed and extensive are the illustrations we have provided, yet we still fear that people will depart from the root and follow the branches. Thus, if we speak of the Way but do not speak of affairs, there would be no means to shift with the times [Conversely,] if we speak of affairs but do not speak of the Way, there would be no means to move with [the processes of] transformation. [3]

Of Clods and Chariots

The first of the branch chapters asks about techniques (shu 術) that are useful to a ruler. In line with its Daoist roots, it proposes that the best way of ruling is not by action, but instead by non-action (wuwei 無為), or by optimally minimising action. The ruler’s task is not to be constantly making decisions. Instead, it is to establish the conditions – both internal and external – where the intervention required is at a minimum. Put in place just, fair and impartial laws and policies that “accord with the human heart”, cultivate yourself to the greatest degree possible, and the state will more or less govern itself.

The text even suggests that the very best kind ruler should be cloddish (the term in Chinese is kuairan 塊然): self-contained, inactive and unmoved.

The ruler’s techniques [consist of] establishing non-active management and carrying out wordless instructions. Quiet and tranquil, he does not move; by [even] one degree he does not waver; adaptive and compliant, he relies on his underlings; dutiful and accomplished, he does not labor. [4]

This is not about absolute non-action. It is about the ability to maintain an inner tranquillity and unmovingness even while in the thick of the onrush of external events.

The effective ruler, the text says, is like the famous charioteer Zaofu who “smooths the ride by controlling the reins and bit and regulates the speed by harmonising with the horse’s lips and breathing.” Just like a skilled charioteer, a paragon ruler will expend only the leastmost energy, drawing on inner reserves of stillness while remaining responsive to the changing terrain, the galloping of the horses and the direction of travel. [5]

Resonance and Sensitivity

The images of the clod and of the charioteer may seem at odds. But to make sense of the Huainanzi’s position, it might help to explore one of the text’s more puzzling concepts. And that is the idea of resonance or ganying.

The idea of ganying or resonance is that human beings exist in a sympathetic relationship with the rest of the universe. We are quiveringly sensitive creatures, our senses, our bodies, our emotions, and our thoughts attuned to changes in our environment. Just as, when you pluck a string on a musical instrument, another string attuned to the same note thrums in response, we thrum and hum in mutual harmony with the other things of the world. We are sensitive, quivering creatures, fully immersed in a sensitive, quivering world. The philosophers of the Huainanzi also propose that the universe, or at least the social world, is similarly responsive to us: by means of just rule, a good ruler can stir the hearts of the people to sincerity (if this seems implausible, remember how we often accept the reverse unthinkingly: the notion that unjust or corrupt rule is more broadly corrupting of a culture as a whole). This stirring of sincerity through resonance is what the text means when it says that the cloddish leader rules by means of “wordless instructions.”

However, the idea of resonance takes the text into a strange territory. And the Huainanzi is fully aware of this strangeness. The chapter that explores this resonance is called Lan Ming (覽冥), which translates as “Surveying Obscurities.” And as an example of this obscure resonance, the Huainanzi returns to charioteers. It’s pretty impressive, the text says, to have a charioteer like Zaofu who is so much in control that they control the reins and the bit. But how much more impressive were the mythical charioteers Qian Qie and Da Bing, who:

considered reins and bits superfluous, got rid of whips and cast aside goads. Before the chariot began to move, it was starting on its own. Before the horses were given the signal, they were walking on their own. They paced [like the] sun and moved [like the] moon. They flashed [like the] stars and advanced [like the] dark. They raced [like] lightning and leaped [like] ghosts. [6]

On Chariots and Bicycles, or, How to Avoid Tragedy

Is this any more than wishful thinking, or bad metaphysics? Or is there something in this exemplary charioteering of Qian Qie and Da Bing that is practically useful? Here, it might be worth thinking a bit harder about efficacy and skill.

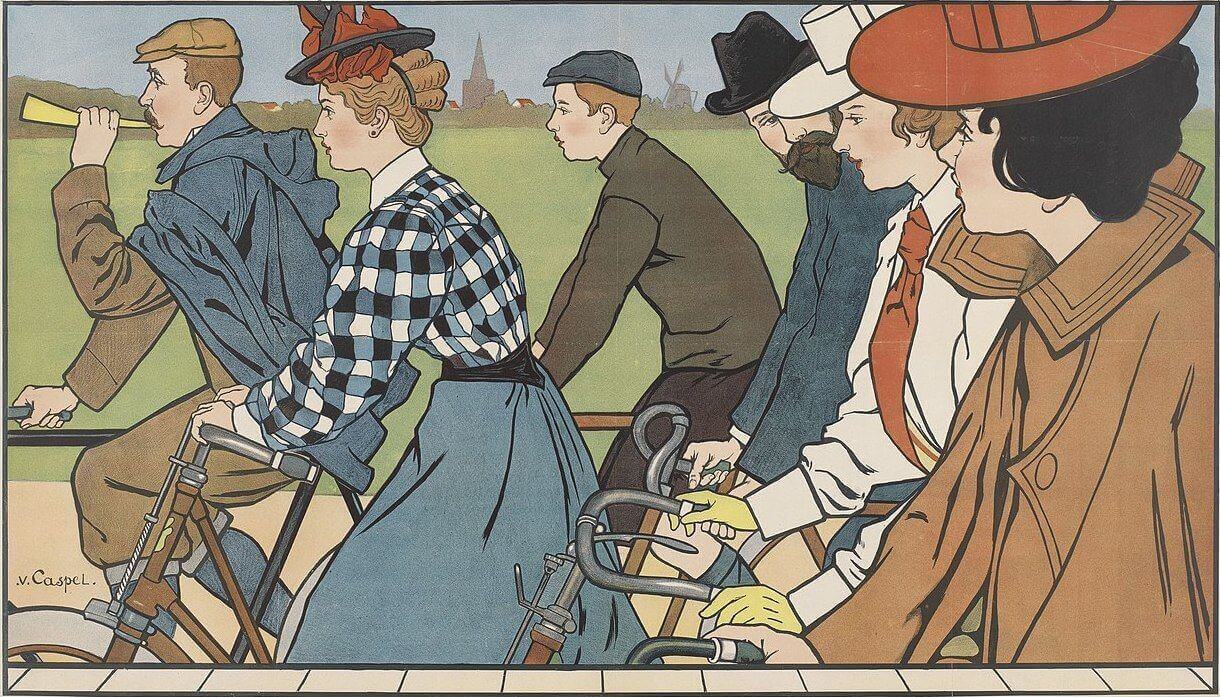

Imagine, for example, that you are a novice charioteer, driving your chariot at speed. Things are going well, but then something changes, and you suddenly feel things slipping out of your control. (If this example is too unfamiliar, and you don’t spend your spare time perfecting your charioteering, imagine instead that you are on a bike that is beginning to career out of control.)

So, what happens when you experience this loss of control? The first thing is that you experience panic and alarm. The next thing is that you desperately try to reassert control. You tug on the reins, yank on the handlebars, squeeze the brakes a little too hard… And, of course, this is precisely how tragedy happens. As you clench up and attempt to reassert control, you lose your sense of responsiveness to the situation you are in, and things start to spiral even further out of control. The chariot begins to tip over, the wheels of the bike start to skid on the gravel…

This experience is (if you are like me, at least) surprisingly common, in all domains of life and not just charioteering and riding bicycles. And it is the very definition of tragedy: we see our imagined fate heading towards us, so we assert our control in an attempt to forestall it. And in ratcheting up our control, we also hasten the onrush of the very fate we wanted to avoid.

The perspective of the Huainanzi suggests that we would do better to move in a different direction: not towards greater intervention, but instead in the direction of Qian Qie and Da Bing, loosening our grip and relaxing into a broader awareness of the unfolding situation. Non-action, resonance, sensitivity. In this way, we might find that the momentary danger passes, and that we are once again, through processes that feel obscure and even almost magical, driving our chariot with consummate skill.

However, as a way of avoiding tragedy, nothing is foolproof. For all his learning, Liu An himself got it badly wrong. Driving his chariot too hard, he started to harbour ambitions to the imperial throne. An imperial commission investigated his supposed crimes. One of the most damning pieces of evidence they turned up was that Liu had ordered an imperial seal to be carved for his own use.

The philosopher king was found guilty, and in the year 122 BCE, as the palace soldiers came to arrest him, Liu An committed suicide.

Notes

[1] John Major, Sarah A. Queen, Andrew Seth Meyer, and Harold D. Roth (editors), The Huainanzi: A Guide to the Theory and Practice of Government in Early Han China (Columbia University Press 2010) p. 867

[2] ibid. p. 848

[3] ibid. pp. 848-9

[4] ibid. p. 295

[5] ibid. p. 321

[6] ibid. p. 222

Further Reading

Books

The translation by John Major, Sarah Queen and co. is exceptionally readable, and well worth getting hold of. The abridged version, published as The Essential Huainanzi, is a good selection of the greatest hits from the text.