I’m in the middle of editing my next book. It’s a big nonfiction book, and it deals with big themes: loneliness, immigration, urbanisation, politics and philosophy. It is easy to get weighed down with all of this. So as I edit, I am using a mantra I’ve stolen from the Italian writer Italo Calvino. The mantra is this:

Subtract weight!

We often associate meaningfulness with weight and with heaviness. We believe that great books are heavy. We believe that great truths are heavy. We believe that great thoughts are heavy. We mistrust lightness. We think it is the same as frivolity. We tell ourselves that to write seriously, to think seriously, and to live seriously, we have to embrace heaviness.

But in his book Six Memos for the Next Millennium, Calvino says we are wrong. Heaviness is not the only way of writing. It is not the only way of thinking. And it is not the only way of living.

Lightness is a virtue too. And it is a virtue, Calvino claims, that can lead to changes in perspective. When we feel ourselves oppressed by heaviness, lightness can offer us a way out.

Whenever humanity seems condemned to heaviness, I think I should fly […] into a different space. I don’t mean escaping into dreams or into the irrational. I mean that I have to change my approach, look at the world from a different perspective, with a different logic and with fresh methods…

Calvino isn’t talking about escapism. He’s talking about finding creative solutions to the problems in which we are entangled. Calvino’s novels all try to explore new approaches to the world, to explore the world from these different perspectives, using different kinds of logic and different methods. He writes,

My working method has more often than not involved the subtraction of weight. I have tried to remove weight, sometimes from people, sometimes from heavenly bodies, sometimes from cities; above all I have tried to remove weight from the structure of stories and from language.

A View from the Branches

Calvino’s novel, The Baron in the Trees, is a fabulous example of a book that has its weight removed. It touches on philosophical issues about the nature of human progress, about reason, and about our relationship with the natural world. But Calvino explores these through a fable that is funny, sweet, and so airy that it almost floats off the page.

At the start of the book, Calvino’s hero twelve-year-old hero Cosimo is served a dish of snails prepared by his sister. Out of solidarity with the snails, he refuses to eat. Instead, he climbs a tree and vows never to come down.

By sunset, he hasn’t come. Nor by the next day. And soon it becomes clear that Cosimo is never coming down, that he will spend his entire life up in there in the branches. As the book goes on, through looking at the world from this new perspective, Cosimo can raise all kinds of fresh questions about the earthbound existence of his contemporaries.

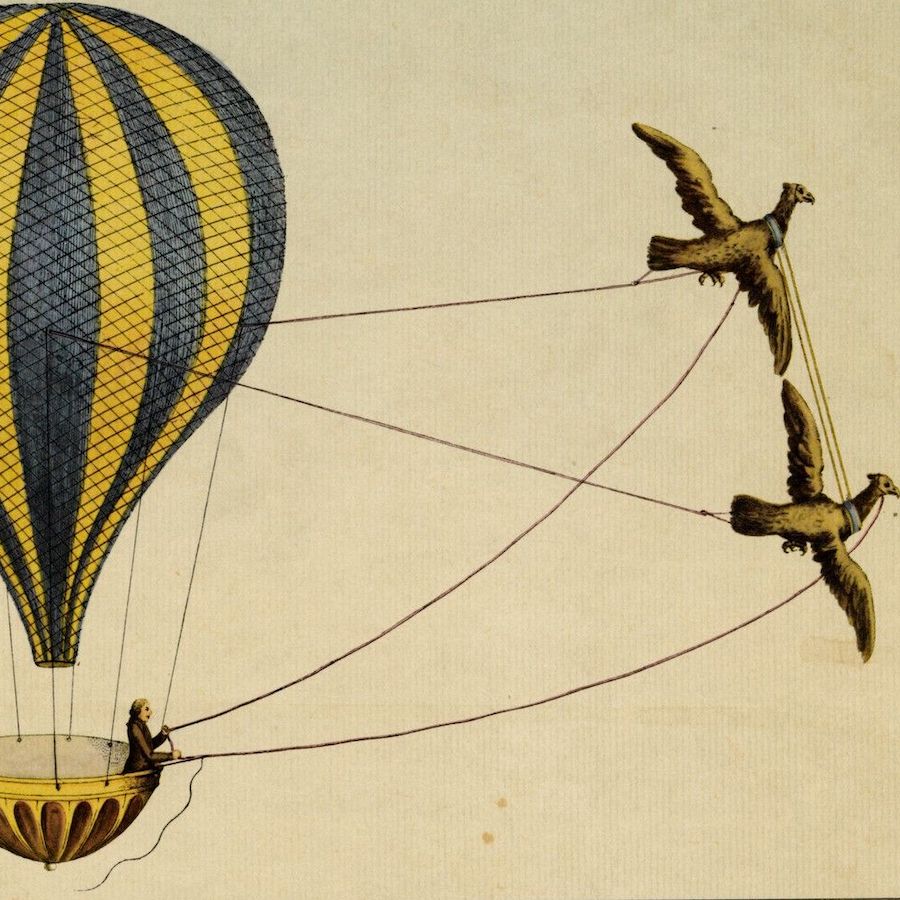

As for how the book ends (spoiler alert!), after a lifetime spent living among the branches, the dying Cosimo grips hold of the anchor rope of a passing balloon. The balloon sweeps up into the sky, and he disappears from view. Calvino writes:

So vanished Cosimo, without giving us even the satisfaction of seeing him return to earth a corpse. On the family tomb there is a plaque in commemoration of him, with the inscription: ‘Cosimo Piovasco di Rondò — Lived on Trees — Ever loved earth — Went into sky.’

And then Calvino ends by reimagining the story itself as a tangled canopy that runs on and on forever,

swarming with cancellations, corrections, doodles, blots and gaps, bursting at times into clear big berries, coagulating at others into piles of tiny starry seeds, then twisting away, forking off, surrounding buds of phrases with frameworks of leaves and clouds, then interweaving again, and so running on and on and on until it splutters and bursts into a last senseless cluster of words, ideas, dreams, and so ends.

As an ending for a novel, it is lovely, it is lightweight, and it is strangely moving.

Balloons Made of Words

So, under the influence of Calvino, I am hard at work subtracting weight from my book. The more weight I subtract, the less earthbound I hope my words will become. I hope that this subtraction will allow my writing to float up into the sky, a balloon made of words.

From up there, maybe I can look at things differently. Maybe I can get new perspectives, look at things with a different logic.

For me, this subtraction of weight means several things.

- It means paying attention to individual sentences.

- It means, as Verlyn Klinkenborg says in his brilliant Several Short Sentences about Writing, knowing what each sentence says, what it doesn’t say, and what it implies.

- It means cutting out those paragraphs that only exist to shout, ‘Look how clever/deep/profound I am!’

- It means reminding myself that often stories will take you to the heart of things more quickly than pages and pages of theory.

- It means keeping insecurity at bay because insecurity is one of the things that makes me try to weigh things down and show that I am serious.

- And it means making sure that the experience of writing and reading is not about duty but about pleasure.

So far, the process of subtracting weight is going well. Now I have given up on my commitment to weight, is becoming easier to think through the big questions I am trying to explore. It is becoming easier to make new connections. And it is also becoming more pleasurable.

Lightness and Life

Subtracting weight is about valuing lightness. It is about getting over the idea that weight is necessarily good. It is about developing a taste for seeing things aslant, looking at them from different perspectives. It is about seeing the virtue in play, pleasure and fun.

As I’ve been subtracting weight from my manuscript, I’ve been thinking about the habit of heaviness more broadly. I like to think of Calvino’s Six Memos for the Next Millennium not just as a guide for literature, but also a guide for life. When Calvino talks about the virtues of lightness, what he is proposing is not just a different way of writing, but a different way of thinking and of acting.

Calvino suggests that once you give up on the habit of heaviness, you can glimpse new perspectives, make new connections. For Calvino, we need lightness. Perhaps, when many of us feel condemned to heaviness, we have never needed it more.

Lightness makes the pulse race a little faster. It lifts the spirits. It reminds us that although not all things are possible, many things are. And it shows us how to break free of gravity for a moment, forgetting heaviness, and finding new ways of thinking, acting and living.

References

Italo Calvino (2019). The Baron in the Trees. Vintage.

Italo Calvino (2016). Six Memos for the Next Millennium. Penguin Modern Classics.