Introduction

Welcome to the first ever Philosopher File interview! In this interview, I’m talking to Anna Ezekiel, a philosopher originally from Scotland and now based in Hong Kong. Since 2014, Anna has worked as an independent scholar, living with ME / Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. She has a particular interest in German women philosophers.

Anna’s hugely readable and enjoyable translation of Karoline von Günderrode’s Poetic Fragments was published by SUNY Press 2016, and she is currently working on a further book of translations by Günderrode called Philosophical Fragments. She is interested in expanding the philosophical canon to include a wider diversity of voices, and to expand our notion of what philosophy is, or what it could be.

“I believe that the lack of a single, universally agreed-upon definition of what philosophy is or what form it should take is a strength of the philosophical project." — Anna Ezekiel_, Philosophy and Genre._

On expanding philosophy, and independence: Anna Ezekiel

Q: Welcome, Anna Ezekiel. I want to start by asking how you got into philosophy, and what drives you to keep on working?

I got into philosophy for different reasons than the reasons that drive me now, although there’s a common thread of wanting to expand my ways of thinking about the world. I began with curiosity about how people from different cultures think and act (my BA was in ethics and comparative religion). Then I became fascinated by thinking about language, myth-making and community — topics that I wrote about for my MA and PhD theses.

But by the time I finished my PhD I was burnt out. My work felt meaningless, like publishing for the sake of publishing. Then I came across a paper by Christine Battersby about the German philosopher Karoline von Günderrode, and I realised there was a world of philosophical writings by historical women that has never been properly addressed and that could revolutionise how we think about philosophy. But for that to happen, someone needs to do the work of picking apart these women’s writings and explaining the philosophical positions they present.

It takes a lot of work to unearth what’s new and valuable in a writer’s texts, and with these women we have to start right from the beginning. So this is what I do. My translations, introductions and articles are intended to help advance our understanding of Günderrode’s thought. I think of my work as part of a joint effort to expand philosophy, not just to include the work of women and other excluded groups, but also to broaden the philosophical exploration of the ways people think and encounter the world.

Q: You are an independent scholar. What challenges does this represent? And what are the advantages of independence?

It’s very challenging working as an independent scholar. The biggest challenge is money. Not only do you have to work freelance — and most philosophical work is not paid, which is one reason why I do so much translation — but you’re also eligible for very few awards, most of which require institutional affiliation. It’s also difficult to get access to texts. Fortunately, various universities let me use their collections, and it’s worth knowing that universities in the UK (for instance) charge a relatively low fee to use their libraries and online resources. At one point, I did a second Master’s degree to obtain library access.

Another challenge is that it’s hard to gain recognition as an independent scholar, though this is changing because the academic job market has recently been so terrible that most people in the field are now aware that very good scholars are often unable to get reliable work.

However, I do love the independence. I don’t miss writing funding applications. I’m happy to avoid administrative duties. And I can work on absolutely anything I want. It would have been hard to go on the job market with a project on a lesser-known philosopher like Karoline von Günderrode, but as I wasn’t very interested in finding a university-based job I didn’t have to worry about that. And, as it happens, my work on Günderrode has corresponded with a surge in interest in historical women philosophers. It’s been a privilege to contribute to this movement.

But the biggest advantage for me is the flexibility. I have ME/CFS and chronic pain stemming from spinal surgery in 2014, which make a typical academic career impossible. As an independent scholar, I can fit my work around my unreliable body, and I manage to work quite well like that.

On free will, death and identity: Karoline von Günderrode

Q: Very few English-speaking philosophers have even heard of Günderrode. So who was Günderrode, and why does she matter?

Karoline von Günderrode (1780–1806) is often described as a Romantic thinker, and she was an important bridge between earlier and later German Romanticism. She came from a noble family with a passion for literature and philosophy, and until the end of her short life, she retained a thirst for knowledge and for recognition as a writer. Her suicide at the age of twenty-six led to a long-running interest in her biography: there are dozens of novels, plays, poems, paintings and pieces of music about Günderrode. Both her life and her death have often been considered tragic, slightly scandalous, and in keeping with Romantic ideas.

But Günderrode’s ideas influenced many better-known intellectual figures of her day, as her correspondence suggests. These lines of influence, and Günderrode’s posthumous fame, make it strange that few people have read Günderrode’s work seriously as philosophy, at least until recently. But Günderrode presents distinctive and fascinating arguments on gender, free will, identity and consciousness.

When reading Günderrode, and many other women writers of the time, you get a very different perspective on philosophical and literary movements to those perspectives — based entirely on work by men — that have been dominant until now.

Q: One of the distinctive contributions made by Günderrode is her view of free will. Could you say more about this?

Günderrode’s contributions to the debates about free will versus determinism that were raging at the time she wrote are understated, deliberately ambiguous, and nuanced. She explores this topic mainly in her plays, which is a format that allows her to present a variety of viewpoints on the question without committing to any of them.

This makes it difficult to say conclusively what she claimed about free will; however, it is clear that she thinks two things are crucial to the question: (1) the impact of social conditions on one’s actions; (2) the impact of one’s actions on the freedom of others. And she suggests that these factors can be obscured when we take an overly abstract approach to free will.

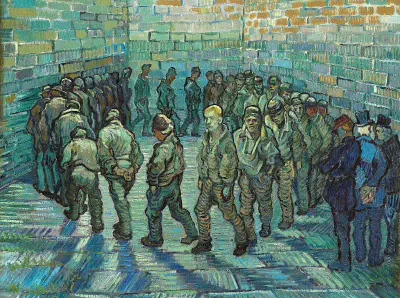

In many of her plays, Günderrode puts the question of whether a powerful male character’s actions are free or determined at the front and centre. But around these characters, Günderrode also shows women, servants and others for whom the answer to whether they can act freely is, in one sense, a resounding “no.”

Despite this, Günderrode shows female characters finding ways to realise their decisions that take account of these constraints placed upon them by other people and external circumstances. Behind the conflict between free will and determinism enacted by the male protagonists in her plays, the female characters reveal a way of acting that is not independent of external events and forces, but also not completely constrained by them.

Q: In your book, you explore Günderrode’s distinctive and fascinating philosophy of death, which links to a complex set of ideas about selfhood, love, metaphysics, and the mutability of things. What’s going on here?

Günderrode’s writings on death have always captured people’s imaginations, especially because of her suicide, but it’s unfortunate that because of this most readers have tended to view her as simply morbid, instead of investigating what she was saying.

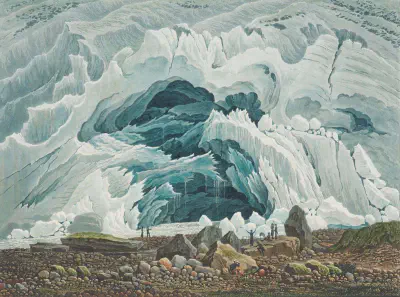

Her ideas about death are slightly unusual and, as you say, closely tied to her metaphysics and her conception of the self. Günderrode’s basic metaphysical picture is that the universe is made up of “elements,” which join together in groups to constitute beings (including human beings) and objects in the world. She claims that when these beings/objects die or are destroyed, the elements are redistributed and then create new entities by joining together with new elements according to “laws of attraction.”

This means that, for Günderrode, death is not an ending. Instead, we go on to experience new ways of being — we go through a kind of reincarnation. Not only that, but because for Günderrode beings are constituted by attraction between the elements, death is a union with those we love; and the feeling of love we experience while alive is our sensing of the physical attraction between the elements out of which we and our loved ones are made. Once we die and decompose, the elements are freed to join together with those of our loved ones and form new entities. We won’t just be together with the people we love; we’ll join with them at a fundamental level and become a new being.

This also has implications for Günderrode’s claims about consciousness and personal identity. If it’s the case, as she claims, that individuals can be shaken up and divided into parts that then join together with a bunch of parts from other individuals, then who we are can’t be a function of our current consciousness of being an individual human being; we must be able to experience different forms of awareness and have a different sense of ourselves that changes, but survives, as we go through this process.

It’s quite a strange and radical understanding of identity.

Q: The Poetic Fragments contain poems, plays and other kinds of writing that don’t, at first glance, look like philosophy. Is this out of necessity? Or can writing like this accomplish things a more overtly philosophical style can’t?

It’s true that the constraints of being a woman in the early 19th century restricted the ways in which Günderrode could write. But there are also good reasons inherent to her subject-matter that make literary forms a useful means of communicating. I mentioned above that Günderrode uses her dramas to convey several viewpoints on the question of freedom and power: drama is a good format for this, as it allows an exploration of the implications of different approaches to the human desire to be free while retaining a certain agnosticism and humility about which of these is correct.

Günderrode also uses literary forms to think through and communicate what the implications of her metaphysical claims are for our experience. For instance, she explains her metaphysical views about the elements in her more academic, essay-like writing. Then in her literary pieces, she shows individuals experiencing this pull between some of their own elements and those of another person — experiences of love, connection, or friendship.

Another example is in relation to Günderrode’s understanding of personal identity and death. In several of her pieces, including “An Apocalyptic Fragment” and “A Dream,” she uses a literary style to try to convey this non-conscious awareness or selfhood that continues after death. Literature is better than dry academic writing at helping us imagine what it might be like to exist in a way that is not circumscribed by purely human perspectives and experiences. Since Günderrode is presenting a model of identity and consciousness or awareness that is very unconventional and different to how we usually understand ourselves, using evocative language can help us imagine things differently to how we tend to understand them on the basis of our usual categories.

Q: I’m always interested in this question of style. Plato wrote in dialogue form. Parmenides wrote in verse, as did Lucretius. Günderrode wrote plays. Are you ever frustrated by the style constraints in academic philosophy?

On a personal level, I find an academic style of writing philosophy quite comfortable: it seems to suit my style of thinking and communicating to write in a structured, logical, very literal way.

But what is frustrating is that this is often seen as the standard for presenting all philosophical thought, and I don’t think it’s necessarily the best for all philosophical explorations, all individual philosophers or all audiences. Just because philosophy can be done in that way, and just because that’s what we all tend to be trained in, doesn’t mean it’s the only or the best way to do it. It would be nice not to have to preface every investigation of a piece of non-academic writing with a painstaking argument for why it should be taken seriously by philosophers.

Conclusion

Q: What’s next on the horizon for you and your work?

I’m finishing up a volume of translations of what I consider Günderrode’s most philosophically interesting pieces, titled Philosophical Fragments, for Oxford University Press. __ I’m guest blogging monthly on historical German women philosophers for the Genealogies of Modernity project, and I’ve started my own blog on historical women philosophers and philosophical genres. I also have six or seven articles and book chapters on Günderrode that I’m committed to. But after the end of 2021, I’d like to move on to work on other historical German women philosophers. In particular, Günderrode’s friend Bettina Brentano-von Arnim has some radical things to say about philosophy and music, and someone needs to begin a systematic exposition of the philosophical contributions in Rahel Varnhagen’s letters.

Q: Finally, if you could give any advice to an aspiring philosopher, what would it be?

Find your people: Develop professional relationships with philosophers and other scholars, within philosophy departments or outside them, people you enjoy working with, who build you up, who are interested in your work, and who are working on things that excite you.

Q: Thank you, Anna Ezekiel! It’s been a pleasure talking to you.

Further Reading

Books

Ezekiel, Anna. Poetic Fragments, by Karoline von Günderrode. Translated and with Introductory Essays by Anna C. Ezekiel. Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2016.

Gjesdal, Kristin and Dalia Nassar (eds.) Women Philosophers of the Long Nineteenth Century: The German Tradition. New York: Oxford University Press: forthcoming.

Online resources

Follow Anna on Twitter: @annaezekiel1

There is still not much scholarship on Günderrode in English. The best starting point is Anna’s website, ACEzekiel.com (where you can also sign up to her excellent email list).

Read these two excellent articles on the Genealogies of Modernity website: “Discovering the Women at the Heart of Philosophy” (28 October 2020); and “The Woman at the Heart of German Romantic Philosophy” (December 2020).