Introduction

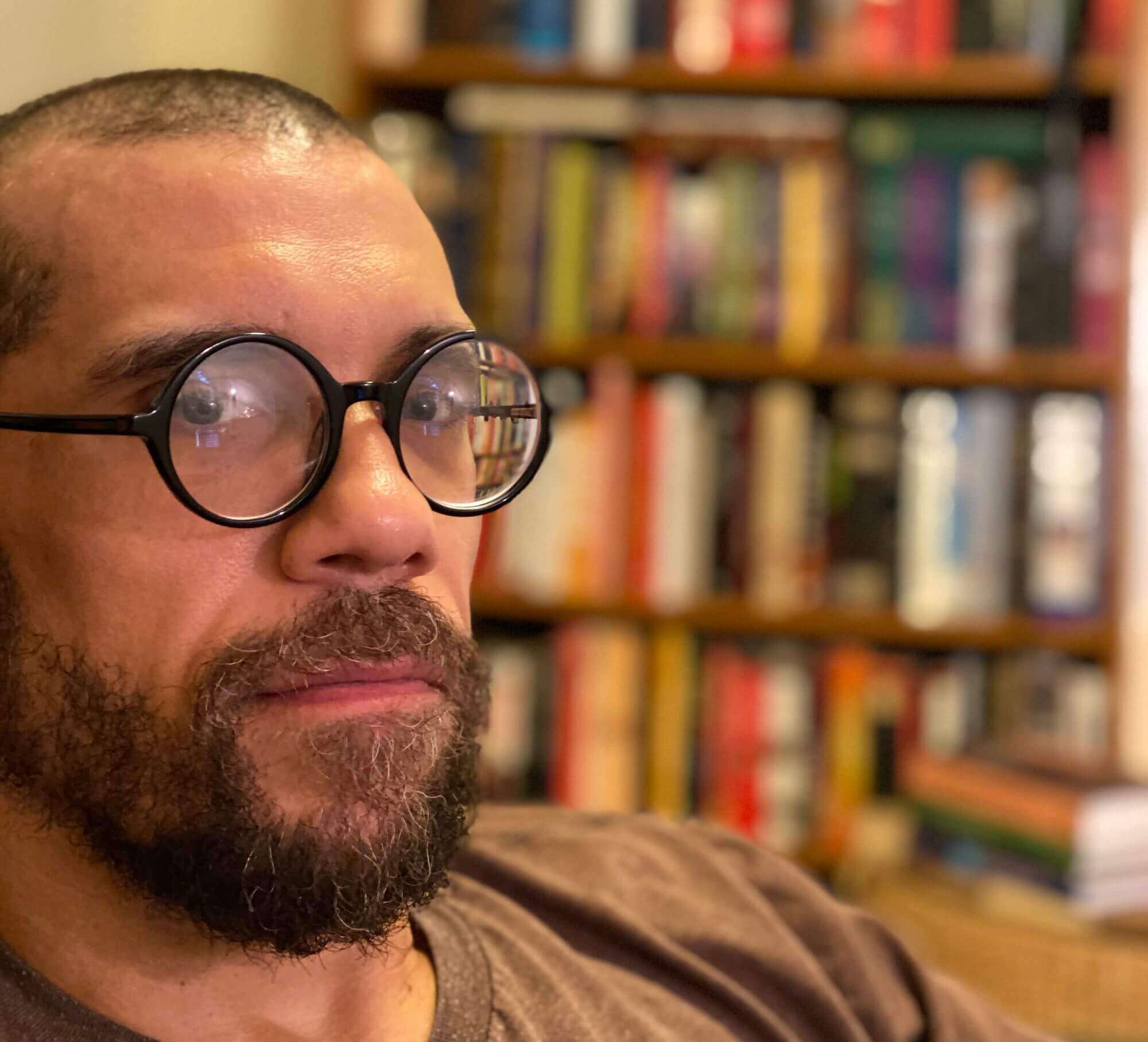

Alexus McLeod is originally from Washington, DC, and now living in West Hartford, Connecticut. He teaches at the University of Connecticut and writes on a host of topics: Chinese and Mesoamerican Philosophy, mysticism, political history, the history of science (particularly astronomy and medicine), and several other things besides. For much of the past year, like many of us, he has been living the hermit life. Camped out in his home office, he has continued his work exploring the riches of the world’s philosophical traditions.

Part 1: Broadening Out Philosophy

Q: Hi, Alexus. It’s great to chat with you. The first thing I want to ask is about your astonishingly broad interests. Sometimes I wonder if there’s anything you’re not interested in. I know you’ve thought a lot about questions of breadth and depth. So in the face of those who claim academic philosophy must be a business of ever-increasing specialism, I’d be interested to hear your defence of pursuing broad interests.

I’ve indeed spent a lot of time thinking about these issues. I’ve become increasingly convinced over the years that we need to re-envision the way we think about what philosophy is and can be. The academy is changing, and our place as philosophers is changing within it. Some lament this, but I think on the whole it’s a good thing. The old ways needed shaking up. Now we finally have to confront questions of change, and how we can adapt in ways that benefit us, our institutions, and the broader society, rather than insisting on doing things the “old way” and thus making ourselves irrelevant. The old way involved appalling neglect of entire traditions of thought of large swaths of the world.

I’m also a methodological pluralist. I think of philosophy as an area in which we should have the room to envision new possibilities, experiment, and continually reimagine what we do. We’re thinking about thinking, about a variety of ways of doing and being. I’ve never been a fan of the view that there’s one particular way philosophy should be done. This seems to me to stifle one of the things that makes philosophy useful and different from other fields. If there is no place for methodological exploration in philosophy, then where is there place for it? Philosophy seems a natural area for such a thing.

Specialization can certainly be valuable, and it has brought us great advances in several fields, particularly in the sciences. But this model is not fruitful for every area of intellectual pursuit. Traditionally, philosophy has been the area in which we push the boundaries, consider what is possible, experiment with new ways of thinking about the world. The sciences emerged from philosophy because of this—it was through entertaining new possibilities and trying different things that we discovered powerful new ways of understanding the world. If people in the Middle East and Europe had just stopped back in the Middle Ages and said, “okay, no more methodological divergence—we’re just going to write commentaries on Aristotle making his work useful for Christianity from here on out,” we would not have seen the emergence of the various sciences and fields we see today from this tradition.

In a different age, people like Leonardo da Vinci, Aristotle, Ibn Sina, al-Tusi, and Zhang Heng were seen as the ideal scholars. Who had broader interests than they did? And their contributions certainly were not limited by their breadth. So as far as our tendency to focus narrowly today, I think this has to do with both trying to be like fields in the sciences and with our professional focus on “branding”. It’s hard to generate a name for oneself in philosophy (and probably other academic fields) without being the person uniquely associated with some specific area or problem. We’ve followed the same model as branding in entertainment, companies, and other parts of our economy. We’re encouraged to focus our product, and build a brand around that. To work more broadly, we have to break out of this mould.

But this is all part of what I mentioned at the start, our need to re-envision what it means to do philosophy professionally. I don’t think that the current model is ultimately working for us. It’s not helping us as thinkers, and it’s also not helping demonstrate our value to (often sceptical) academic institutions. Because at the end of the day, we’re going to have to be able to honestly say something about what we contribute to society and the institutions we’re part of.

Q: So is there anything you are not interested in?

Not really! Even when I come across something I’m not initially interested in (which doesn’t happen a lot but does every once in a while), I try to make myself interested in it, and that usually succeeds. The main reason I got into academia in the first place is that I love learning. I enjoy writing, but for me, writing has always been connected to the process of learning things. I never set out to make a big discovery or come up with some new idea that everyone is talking about years down the road. I just really love learning, I get excited about seeing the world in new ways (or new to me at least), and I want to impart something of that enthusiasm to my readers, audiences, students, children, and others I engage with. And I don’t like to stay inside a box with my learning—I want to learn about different people, cultures, parts of the world, whatever.

There’s far too much fascinating stuff out here to limit ourselves to one little corner of the world. I like to browse library shelves and select things to read pretty much randomly, and this way I usually find some topic that sparks my interest, and it generates a different project to focus on every couple of years. This way, I can pick out something I’ve been learning about that’s particularly interesting or stayed with me, and develop that further into a writing project. This helps me to make connections I never would have seen otherwise, and to develop ideas I would never have had the ability to develop on my own.

We have a tendency in philosophy to view innovation as the realm of the solitary genius in the armchair, but innovation never really works like that. We come up with new things as a result of new experiences and engagement with others. Every intellectual renaissance in history happened after contact with new people and ideas. The greatest genius in the world sitting alone in the armchair is not going to come up with anything but the same old thing over and over again.

Part 2: Learning from Maya philosophy

Q: The title of your book, “Philosophy of the Ancient Maya: Lords of Time” puts the idea of time at the very centre of Maya philosophy. So what are the central preoccupations of Maya philosophy?

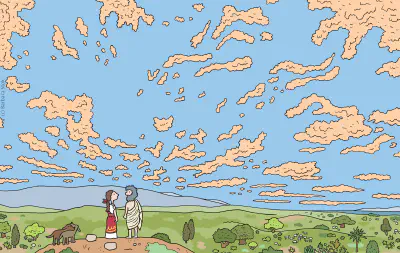

Some of the major issues are time, identity (personal identity and the identity of objects), being and worlds, the human role in shaping the world, change and becoming, government and rulership, and sacrifice. One of the interesting things is that some of these topics may have an outsized influence based on what we know because of the nature of the textual tradition. The vast majority of texts from early Maya sources we have today are from monuments such as stelae and architecture, and these were the texts that tended to commemorate rulers, particular important ritual events and time periods, and important communal events or times.

We know that there were also more perishable texts like bark paper books in the pre-Columbian Maya region, but most of these have been lost to the ravages of time. Things like that don’t tend to keep well in the humid rainforest environment of the Maya region. In the sources we have, including several post-contact texts like the K’iche’ Maya Popol Vuh and the Yucatec Chilam Balam books, the concerns are very much with the kinds of philosophical topics I mentioned and with classic issues like truth and the meaning of life. What we find in Maya Philosophy is very much like what we see in other ancient traditions, as far as its breadth—they were very much concerned with the range of philosophical issues. It’s a fascinating tradition.

Q: You draw a connection between this idea of time and the creative role human beings play in shaping the world. Do you see this emphasis on the human role in ordering time as something of only historical interest? Or do you see it as a philosophical insight with much broader applicability?

Absolutely I see it as something with broader applicability! This is a great question, and something I’ve been thinking about quite a bit recently. Actually, one of the first things that really drew me to Maya thought (and Mesoamerican thought more generally) was the strong conception found there of how ritual activity can shape and complete the world and the self (as a component of the world). Even though I read very broadly, I’m generally drawn to spend more time with texts, thinkers, and traditions that I think get things right. I’m an intellectual historian to a certain extent, but also someone who wants to engage with and learn from these traditions. The texts and traditions I work on are ones that I feel hit on important truths that are less prominent or even ignored in our modern discourse (at least in the West).

When I first encountered Maya views of personhood and identity, my thought was “this is not only historically fascinating—I think this is true.” These views, as well as the Maya views of ritual and the human role in the construction of the world (and so many other things as well!), are things we can learn from and adopt. Ritual has an important role to play in organizing our world and structuring the self. We only have a social identity, for example, through the performance of ritual—language, religion, associations, daily activities, characteristic ways of acting, etc.

According to the Maya, we can enact identity through ritual. We can literally become someone else, to manifest their essence via substitution (k’ex). This is one of the things I find most compelling and powerful about early Maya views of personhood. We can communicate with our ancestors and with other aspects of the world that constitute us, through ritual performance. If we can enact their characteristic responses, mirror their activities, and occupy their roles, we can literally become them. This is why performance rituals, such as the performance of the activity of the gods recounted in texts like the Popol Vuh, are so important for the Maya. We enact things in the world through performance. The importance of ritual in Maya thought can also help us to reflect on our own regular activities, how these are rituals, and just what we are creating through these actions. I suspect that many of us end up creating much that we don’t want to, just out of the failure to reflect on the rituals we perform and their results.

Q: In your book, your comparative reference points are in Chinese philosophy rather than in the philosophical traditions that trace their heritage back to Ancient Greece. You talk in the book about “decentring the West”, undermining the assumption that so-called “Western” philosophy should be seen as the yardstick by which all other philosophical traditions are measured. Can you say more about this? And what would a thoroughly decentred philosophy look like?

Thanks for this question—that’s indeed one of the main things I’ve hoped readers would take from this book! One of the things we tend to most often see in comparative philosophy is the presentation of a “local” (generally “non-Western”) tradition paired with the West. This seems to me rooted in the idea that the West is universal in scope, while other traditions are provincial. We often use Western thought as the framework to understand thought anywhere else in the world. Thus, in China you find that it’s common for philosophy departments to include Chinese Philosophy and Western Philosophy, but nothing else. Or departments in India to include Indian and Western Philosophy. Each place respects its own local tradition and then sees the West as the essential other, the means of translation of a local tradition to a more universal form. We see this all the time in the West as well, with how we think about and position non-Western thought. We take Western scholarship or categories as giving us the “natural kinds” through which we then try to understand what is going on in ancient China or India or Mesoamerica. So we ask questions such as “what was the early Maya view of truth?” rather than “what are the Western views of itz?”

When I think about decentring the West, it’s not to somehow denigrate or jettison Western thought. The intellectual heritage of the West is great, but it’s not greater than that of the rest of the world, and shouldn’t be that by which everything else is measured. Decentring the West involves taking concepts from other traditions seriously in our own thinking. Maybe when we think about ethics, for example, we can think in terms of the Chinese concepts of ren and li and not only in terms of virtue and duty. We investigate other traditions in terms of virtue (a classical Greek and Roman concept) all the time. So why can’t we investigate traditions in terms of ren?

Are the concepts centred in the West truly universal, and those elsewhere only localized copies of those? I don’t think there’s any reason to think this. And a truly global philosophy will look much different—we will have reason to consider things in terms of ren and li and dharma and itz and teotl as much as we do virtue and duty and agency. Much of the reason philosophy seems stuck in certain ways of viewing the world is that we often refuse to learn from other traditions, we refuse to take on the ideas of other traditions as our own in the way we do take on the ideas of the so-called West, and instead we try to understand those traditions by situating them within or reducing them to the categories of the West.

When I was in graduate school, this was all the craze. Reading a text like chapter two of the Zhuangzi, and trying to figure out which kind of more familiar Western theory this represented. Was it scepticism? Conventionalism about language? How did it fit into the categories of contemporary Western philosophy? Certainly we can gain some interesting insights from such projects, and I don’t want to say that doing this kind of thing is fruitless or a waste of time. I’ve read some incredibly good and creative work in this vein. But it seemed to me that very few people, if any, were engaging in different kinds of projects that could help expand our conception of what is philosophically possible, deepen our projects, and contribute to our understanding of the world, rather than a seemingly reductionist project of fitting these into familiar structures.

Q: At the end of your book, you say that we should engage with Maya thought and modern Maya people, “in the hopes that we may have a true fusion such that one day there will no longer be Maya or Westerners (whatever that means), no longer Chinese, Indians—but a true fusion of all of these groups, such that our descendants can claim the traditions of all of these cultures as their own heritage.” Is there something utopian in this vision of what philosophy could be?

Absolutely. I think that’s a good way to put it. What I see as the end goal of all academic endeavours is a future in which humanity works together and sees itself as one family, with a shared sense of its past, present, and purpose, working together in the service of learning about this world we inhabit and about ourselves. I think we should strive to ultimately become more than what we are, to get beyond the provincialism of nation, race, or tradition. Not to erase the past, but to embrace all of it as all of ours, and to use it to create a future in which we create something new out of the best parts of these traditions, rather than just duplicating them as they were and insisting on keeping walls between them to preserve their integrity. This would be like putting a form-fitting iron cage around a child to stop it from growing into an adult.

I think of myself as an internationalist. I grew up in Washington, D.C., and my friends growing up were from all over the world—the children of diplomats (as is my wife), international businesspeople, and the like. The people around me spoke many different languages and came from many different cultural backgrounds. It always felt to me awkward that, with the world around me so diverse, in the classroom things were so narrow. Was it really only this narrow subset of humanity from Western Europe that created all knowledge, when the other people around me seemed to come from cultural traditions every bit as rich as those of Western Europe? Something was wrong there. When we did learn about traditions outside the West in school, it was always as the “other” rather than our own. It struck me that the traditions of these other parts of the world are as much our own as anything from Western Europe. My ancestors were almost entirely from west and central Africa and the British Isles, not from Greece or France, yet I was taught that Plato and Descartes were “my” tradition, and Confucius, Sankara, or Nezahualcoyotl weren’t. Why?

After years of studying these and other thinkers on my own (as they were neglected in my philosophical training), I realized that not only do they offer essential truths, but they can be seen as part of our shared human tradition as much as Plato or any other influential thinker. There is no reason Confucius, for example, has to be an “other” or someone representing a “different” tradition any more than Kant or Mill or whoever. Personally, I’ve been far more influenced by the thought of Confucius than I have by that of Plato or Kant. Does that make Confucius a more central part of my tradition than those European figures? It just feels bizarre as well as false to refer to Kant as part of “my” tradition while referring to Confucius as part of “other” traditions. And this othering of the so-called “non-West” closes the door on the possibility of those of us in the West learning from and adopting views from these great thinkers as our own, allowing them to shape us. What makes a tradition is what one reads, engages with, responds to, takes seriously. So there’s no reason that we can’t or shouldn’t create an intellectual tradition that includes the thought of the entire world, which we now have unprecedented access to in our globally connected age. The texts of the ancients are part of our shared human tradition. I hope for a day when we all feel completely at ease referring to the traditions of Mesoamerica, China, Europe, Africa, and everywhere else as “our” traditions rather than “theirs”.

Part 3: Doing something new

Q: So what’s next on the horizon for you and your work?

I’ve got a few different projects bouncing around at different stages of development. Most recently, I’ve started working on a new translation and commentary on the K’iche’ Maya text Popol Vuh and the early Chinese text Daodejing. I’m also finishing an Introduction to Mesoamerican Philosophy due to appear in the Cambridge Introductions to Philosophy series, working on a translation (with Yuhan Liang) of the Han Dynasty Confucian text Kongzi Jiayu (“Discourses of the Confucius School”), and thinking about a new history of Han Dynasty Philosophy that I’ve wanted to write for a while. I just finished a long entry for the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy on Han philosophy, and this rekindled my interest in tackling the book project, as there is a lot I wanted to include in that entry but didn’t have the space. Always juggling lots of projects—and I’m sure a few more will pop up in the near future!

Q: And finally, if you could give any advice to an aspiring philosopher, what would it be?

Talking to my own students and others, I find that many aspiring philosophers want very much the same kind of thing I wanted when I decided to pursue philosophy as a career—the space to learn new things, and to work on interesting things that you think really matter (to you and your community). There can be quite a bit of pressure against doing that in professional philosophy. There’s pressure to be ultra-narrow, to work on certain hot topics that people in certain specific circles care about, and not to work on things that people in those circles don’t care about or reject. Pressure to set aside the things you might be more interested in and that really motivate you, to adhere to the standards set by the people in these circles, because of the idea that the only place really worth being is in those circles or adjacent to them. My advice is: don’t sacrifice what you want to do for what you think you’re supposed to do. Nobody will change the field if not us, and none of us makes enough money to justify setting aside what we really want in order to fit in, get a job, etc.

Because that game never ends—there’s always a new pressure to do that thing others want you to do but you don’t. It doesn’t end once you get that job, once you get tenure, once you get promotion. That thing you always really wanted to do gets saved until after the dissertation, then after tenure, then after promotion, retirement, and it never happens at all. Remember why you wanted to be a philosopher. Do it now. Be bold now. Don’t let anyone tell you that you need to wait or compromise on what you’re trying to do for some goal down the line. Once you compromise like that, you’ll just keep on compromising all the way down the line. This is how we all get stuck in patterns none of us actually like, but find it increasingly hard to break free of. This might sound like trite “follow your dreams” advice, but I think people really need to hear it. I can’t tell you how often I hear from younger or aspiring scholars who really want things in our field to be different but are just afraid to cut against that grain or feel like they can’t, which is totally understandable. But there are far more of us out here who support what they’re trying to do than they may think. We’re the only ones we’ve got. We don’t have to do things a certain way just because they were done that way before—so let’s change them! As I mentioned above, this is the time for a change anyway. Academia is undergoing massive (and not always comfortable) changes—let’s use this change to take this field where we want it to go. Use the crisis to dislodge an orthodoxy that should have been toppled long ago but held on for so long simply because it was never forced to change.

Speaking for myself as someone who regularly sees and evaluates job candidates (across the numerous institutions I’ve worked for)—the people who’ve always most impressed me and who I want most to work with aren’t necessarily those who work in my area or whose views I agree with. I want to see the people who are taking chances, who are working on those things they’re really committed to, whether “off the wall” or not. Who are pushing boundaries, rethinking what it means to be a philosopher, bringing new voices into the field. Those voices don’t have to be like mine—although if your voice sounds like mine, that’s cool too. Senior scholars shouldn’t be in the business of duplicating ourselves (though sadly, we are sometimes), but rather should be trying to help others find their own voices. Find your voice, whatever that is—that’s what I want to hear, and that’s what we need to hear.

Let’s do something new.

Brief bio

Alexus McLeod is Associate Professor of Philosophy and Asian/Asian-American Studies at the University of Connecticut. He writes on global and comparative philosophical issues, particularly early Mesoamerican and Chinese Philosophy.

Further Reading

Books

Some good places to start on Maya philosophy are Alexus’s book, Philosophy of the Ancient Maya: Lords of Time, Friedel, Schele, and Parker’s Maya Cosmos, David Stuart’s The Order of Days, and Miguel Leon-Portilla’s Time and Reality in the Thought of the Maya. For Mesoamerican philosophy more generally, check out Maffie’s Aztec Philosophy and Carrasco’s Religions of Mesoamerica. Also, keep an eye out for Alexus’s forthcoming Introduction to Mesoamerican Philosophy.

Online resources

See Alexus’s page on Academia.edu.

This is a great piece on the art of travelling without travelling. “Comparative Philosophy in an Age of Cultural Chauvinism.”

And another piece on how to diversify philosophy. “How Do We Diversify Philosophy? Pluralism Rather Than Inclusivism.”

Finally, Dag Herbjørnsrud’s piece, “The Mesoamerican Philosophy Renaissance”, is well worth a read.