Last week, my thirteenth book—Hello, Stranger: How We Find Connection in a Disconnected World—was published by Granta in the UK. Personally speaking, it feels like a milestone, an event of significance. It’s a book that is close to my heart, one that draws together things I’ve been thinking about for decades—from anthropology to philosophy to my personal experiences of grief and loss. But I’m also aware that, seen in a wider perspective, the appearance of yet another book is a very ordinary thing. As a rough estimate, this year in the UK alone, something like 200,000 other trade and educational titles will be published by mainstream commercial publishers. A whole bunch more will be self-published.

Globally, the figures are even harder to get a handle on. Conservative estimates for books in English alone usually settle around several million unique titles, but there is no exact way of measuring. There’s a Wikipedia page that tries to keep track. However, the data sets are an inconsistent mess: some of the data come from last year, some from as long ago as three decades.

And anyway, there’s no consensus as to how we should count the number of books published. You can do it by counting ISBNs—those handy little ten or thirteen-digit numbers that act as unique identifiers for books, and appear on the back covers as barcodes.

But not all books have ISBNs, and many have several because they appear in different editions. And when you start counting, it doesn’t take long before you get tangled in deeper philosophical questions. Questions like what is a book? And how is a book different from a tract or a pamphlet or a chapbook? So if pushed to give a precise answer for how many books are published a year, the best answer I could do is this: ‘Practically speaking, the number of books out there tends towards infinity.’ In other words, there are enough books in the world for you not to worry about ever running out of things to read.

But for those who are inclined to existential terror in the face of infinity, the bad news doesn’t stop here. Books, after all, are only a small part of the seemingly endless marketplace of words that stretches on as far as the eye can see.

There are newspaper articles. There are blogs and newsletters. There are plays and podcasts. There are stand-up routines and speeches, social media posts and poems. And somewhere in darkened rooms, cunning pieces of AI are conjuring up words, stories and dreams with very little human agency at all, threatening to make us all redundant… This sheer proliferation of words puts the arrival of any new book in perspective. A book is an event. And yet, seen from a global perspective, it’s not such a big event as all that.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this makes some writers anxious. What’s the point of writing at all, when there’s so much out there already? Several years ago, the novelist Javier Marías wrote a piece in the Independent newspaper about why not to write novels. And the very first reason he gave was that there are already too many books in the world. Why add to a pile that is already pretty much infinite?

On the surface, the argument seems persuasive. And most writers I know have fallen prey to it at one time or another. There is so much abundance, such an excess of words, what’s the point of even trying to add to it? It can sometimes feel suffocating, as if all these words are slowly filling up the available space. Just imagining all those library shelves groaning with the weight of dead trees, all those billions of characters on hard drives and servers, all those years of audio streamed out into the abyss… It is simply dizzying.

In a world like this, isn’t it fruitless to sit down and write anything at all?

But this isn’t how words work. They don’t fill up the available space. They create new spaces. Human beings are social animals: we are creatures who are built to communicate and to connect. And when we connect, these connections open up new possibilities, new thoughts, new ideas and new ways of living. When we connect, the world becomes larger. It becomes more interesting, richer, and more complex (and this, more or less, is what Hello, Stranger is all about).

This means that as writers, we should see this proliferation of writing—this unprecedented abundance of words—not as a cause for despair, but as a reason for celebration. Think of all those opportunities to connect, tending to infinity. A world where there is opportunity at every corner is the opposite of cramped and claustrophobic. It is a world that shimmers with the promise of newness. And each act of communication has the potential to broaden the spaces in which we live.

So as Hello, Stranger—one small drop in this endless sea of words—makes its way into the world, this is what I hope for. I hope that for whoever picks it up, for whatever reason, it manages to open up a little more space, to make the world larger, in the same way that the words of others have made my own world larger.

And if after reading the stories in the book, somebody is provoked into telling stories of their own, so much the better. There’s room for us all—because words don’t fill up the available space. They create new spaces for us to play in, to dream in, to imagine in. And the next time you are feeling oppressed by the sheer weight of words in the world, there is no better remedy than this: sitting down to read or to write, and watching as the world becomes larger with every word.

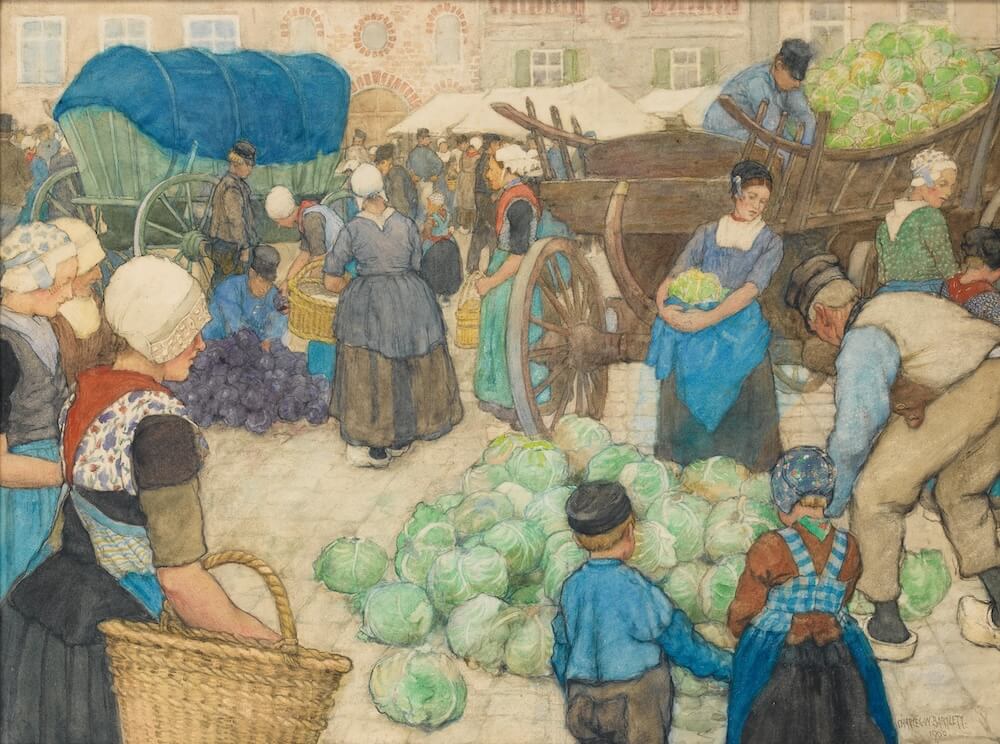

Image: Charles William Bartlett: Cabbage market (1900). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.