A few months ago, I received an email from the university saying that there were funds available for large-scale projects that could be both radical and disruptive, leading to the establishment of research centres that might fundamentally change the way that the university worked.

After a little thought, I proposed to several colleagues that we set up a Centre for Laziness Studies. My colleagues, alas, were not convinced by the idea. And when I looked at the paperwork involved, I realised that I didn’t have it in me to proceed. I felt my will to live begin to drain away, and I decided that this Centre for Laziness Studies was never going to be.

Nevertheless, the idea still hasn’t gone away. And it seems to me that it is still needed. Since my initial proposal, however, I’ve had a chance to finesse the idea a bit. Firstly, it strikes me that ‘Laziness Studies’ gives this a rather industrious — even arduous — kind of air. This seems counter to the initial intention. There’s something monstrous in the idea of a bunch of people wearing themselves out as they industriously study laziness. So now I’m inclined to prefer the idea of a Centre for Laziness. And to forget about the studies altogether.

This is how it would work. The Centre for Laziness (I’m giving it capital letters, because I’m perfectly serious about this) would be a place for mooching and idling and chatting and drinking tea. It would be a welcoming place, a place where you could come and go. It would have books for the browsing. Ideally, it would have some outside space so that, when the weather permitted, it was possible to lounge on the grass. It would be wilfully non-purposive. It would have no targets to meet. It would not contribute to strategic plans. It would be indifferent to Research Excellence Frameworks and league tables. It would have pens and paper and things for jotting down ideas, and probably blackboards and whiteboards and things for sharing ideas. But it would probably have few screens because screens are terrible breeders of industry. It would be a place where you could just lie on your back and think. Or not think. Or do that thing that is just lying on your back, being unsure whether you are thinking, not thinking, or something in between.

The centre could be more than a physical space. It could produce a journal, if it liked. But it wouldn’t have to. As this would be a new field of research, the journal could have a big, impressive title, such as Laziness. It would be published whenever those involved in the centre felt like publishing it, when the pleasures of publishing outweighed the difficulties. It probably wouldn’t be peer reviewed, because peer reviewing is a hassle, and often unwholesome (read Plato on Gyges’s ring, and you’ll know why peer review is always going to be a dubious process). The editorial board would just use their judgement and publish stuff that was interesting, or that gave pleasure, or that seemed to be saying something new or worth saying. Which is, incidentally, how most normal (i.e. non-academic) publishers work. And because the journal wouldn’t be peer-reviewed, it wouldn’t help contributors in their research rankings. This would ensure that those writing for it were writing because they wanted to, and because they had something they really wanted to say, and not because it might get them a promotion, or lead to some far-off, utopian future goal, such as a gilded professorship (I’ve seen those gilded professors, and they don’t look any happier than the rest of us…)

The centre would be run more or less co-operatively. If university managers came knocking at the door, asking what use it was, then it could use low cunning to keep them at bay. A sign reading “CfL Hub” could be posted on the door, short for “Centre for Laziness Hub”. This might just about convince the higher echelons that this was an important space and not to be touched (university managers love hubs, although nobody quite knows the reason why. They also love acronyms.) As for what the centre would then do, it would just go about existing, providing a space for the exercise of laziness, for all those who wished to come there. And it would continue to do so as long as people liked it, as long as it provided pleasure and delight and enjoyment and human fellow-feeling, as long as it was fruitful.

Yes, fruitful! As long as it was fruitful. Because the obsession with work as an end in itself — an obsession that is everywhere, from schools and universities to government circles (witness Jeremy Hunt’s recent comments on China) to businesses — is not fruitful. Or, in the language of an earlier post here on this blog, it is not optimal. It squanders our human talents and efforts. It wears us out doing things that we mostly don’t care about. And when this is taken on a global scale, it starts to look like a vast, stupid, tragic waste.

This culture of work at all costs is far from optimal. If we are interested in cultivating a fulness and richness of life, and doing this for and in the interests of everyone, then this is not how we can go about doing this. It is necessary to make space for laziness. I think of the lovely line from Tony Barnstone and Chou Ping’s translation of Wei Qingzhi’s thirteenth century Poet’s Jade Splinters (詩人玉屑), where it says that literary works arise at ‘the border between hard work and laziness’. And I think of the sixth century Liu Xie, who I am reading at the moment, writing on how writers must yangqi (養氣), or nourish their vitality — they must work, yes, but they must avoid driving themselves to exhaustion and pricking their thighs with needles to stay awake at their desks, they must engage in pleasant trips and idle talk and laughter — if they want to write optimally and live optimally.

And it’s not just writers, of course. It’s all of us human beings. Unless we are accustomed to moving across the borderlands between hard work and laziness, unless we see how both of these can be used to nourish our vitality, then we are not going to live optimally.

But when it comes down to it, of course, we’re not going to get grants to set up centres for laziness. Nor are we going to get much encouragement. The voices raised in favour of hard work — around us and within us — are too pervasive. But until we stop priding ourselves on our hard work and our virtue, and until we stop demanding this grinding drudgery of others, then our individual and collective lives will continue to risk being pervaded by a dull sense of pointlessness, rather than by the richness and value than is proper to human life.

Forget Jeremy Hunt. Forget the demands of the capricious gods who rule our lives. We don’t need to work harder. Instead, we need not to establish not one, but instead many thousands upon thousands of centres for laziness.

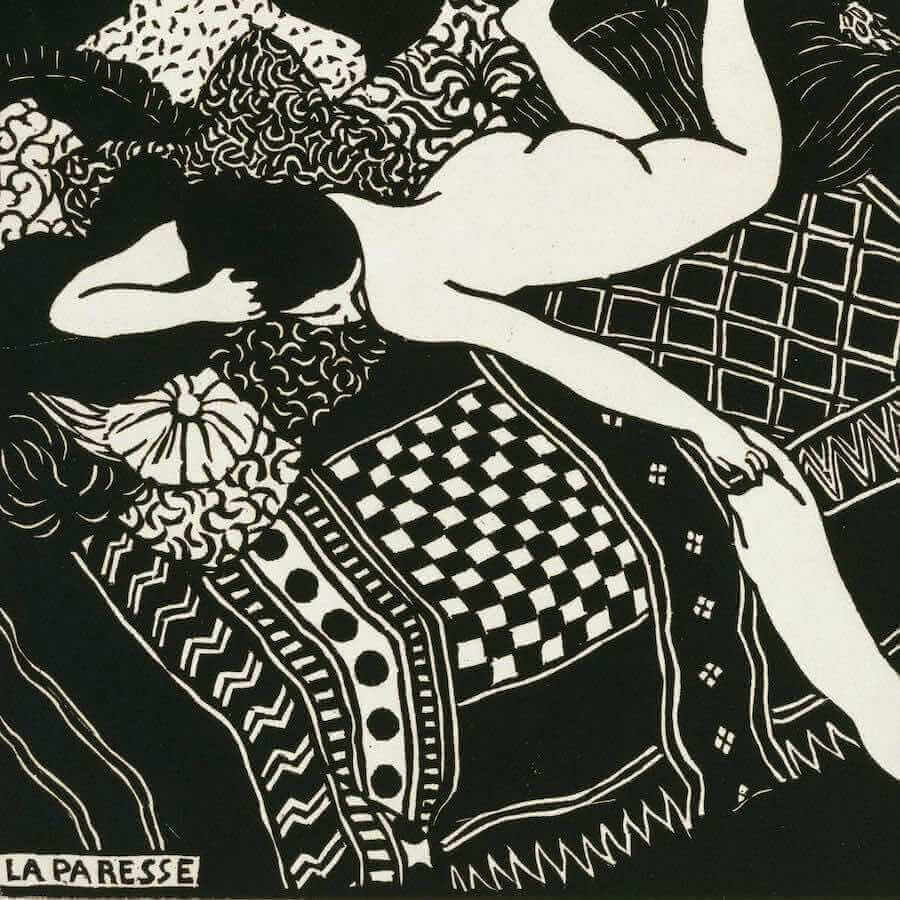

Image: Laziness by Félix Emile-Jean Vallotton. 1896. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.