Philosophers and storytellers

The moment you pick up a philosophy book, if you are anything like me, you will almost immediately feel heavy with a cluster of obligations. The obligation to understand. The obligation to take this great work seriously. And the obligation to read systematically, one page at a time.

But as I suggested in the previous article in this series on reading philosophy at a gallop, this approach can slow you down—to the extent that you end up grinding to a halt. This is why it can be good to pick up the pace and to approach philosophy at speed.

Nevertheless, sometimes even galloping through the book is not enough. And if you are going to get to grips with what you are reading, you have to give up on the idea that philosophy is something you need to read systematically and read haphazardly.

The idea that it is okay to read haphazardly takes some getting used to. Partly this is because our instincts in reading are fashioned by reading fiction. In the last piece, I suggested that we could see philosophy as a kind of storytelling: you start off in confusion, and you move through successive stages until you get to the dénouement at the end. In reading fiction, this is part of the pleasure of it. You can of course peek and skip ahead to the last page to see who plunged the knife into the clergyman’s heart. And nobody should deprive you of your absolute right to do so if this is what you want to do. But you risk spoiling the fun: they don’t call them spoilers for nothing.

But if philosophy is a kind of storytelling, it is different from the kind of storytelling you find in fiction. When reading fiction, there’s usually enough to keep you entertained while you wait for that dénouement. There are sword fights. There are pirate queens presiding over tiny island republics. There are talking animals. There are moody detectives drinking coffee in the diner at five in the morning. All this compelling stuff is the pay-off that keeps you moving through the world of the story until you find out whodunnit.

When reading philosophy books, in contrast, you don’t need to worry so much about spoilers (nor, usually, do you need to worry about sword fights, pirate queens, talking animals and moody detectives). There is a kind of fun to be had in reading philosophy—and don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. But this is not usually the kind of fun that is spoiled by knowing—philosophically speaking—whodunnit.

This means that you are not going to lose out if you start at the end and then move incrementally back to the beginning. Or if you start in the middle and then dip in and out of the beginning and end. Or if you track your own crazy, haphazard course through the text as a whole.

The rights of the reader

At first, this feels counter-intuitive and unseemly. It isn’t how we have been taught to read. We imagine our teachers looking over our shoulders as we flip to page four hundred and something, saying sternly, “Maybe you should start at the beginning…”

Then again, maybe you shouldn’t. In his brilliant little book The Rights of the Reader (or, in the French original, Comme Un Roman), Daniel Pennac argues for the sovereign right of readers to approach books how they wish. One of the things that stops us reading is the lurking sense that we’re doing it wrong, and that in reading this way or that, we are going to be judged.

Here are Pennac’s ten rights.

The right not to read

The right to skip

The right not to finish a book

The right to re-read

The right to read anything

The right to mistake a book for real life

The right to read anywhere

The right to dip in

The right to read out loud

The right to be silent

The first right here—the right not to read—is an important one. Sometimes we think we need to read not individual books, but instead whole traditions, in a systematic fashion. There will always be people who tell you, for example, that you have to read Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. But Plato did not read Kant. Neither did Aristotle. So it’s clearly not obligatory. It might be that reading Kant will help you think through some particular issues. And there are many good reasons to read Kant. But in most normal circumstances (outside of university courses, for example) it’s not compulsory.

So when plotting a course through philosophy, if you pick up a book and it doesn’t speak to you, you should feel free to read another. Or you should feel free to do something else that is not reading: go for a walk, hang out with the cats, bake a cake.

But once you’ve decided you are going to read a particular book, you are still not obliged to read that one book in any particular way, or any particular order. At least three of Pennac’s rights—the right to skip, the right not to finish a book, the right to dip in—are about giving yourself permission to plot your own journey as you read. And this process of finding your own idiosyncratic approach to reading, wilfully and systematically, __ can be fruitful in all kinds of interesting ways.

Reading haphazardly, dipping in, skipping and not finishing are all perfectly acceptable strategies for reading philosophy. You can use philosophy books like divinatory tools, opening them at random to see if they spark a fresh thought. You can start with the final chapter—with a sense of where the journey has taken the writer—and then work back chapter-by-chapter to the beginning. Or you can describe elaborate loops and arcs, moving now in one direction and now in another. All these ways of reading can lead to interesting new thoughts and possibilities, even if these were not what the author themselves intended or wished for.

Ways of not reading

One of the major problems we have when reading philosophy is that we suffer from a myth about what it means to read. We ask each other, “Have you read this book?” Or we say proudly, “I have read the complete works of Søren Kierkegaard.” Then we pause and add, “In Danish.” But we don’t often stop to ask what it means to have read something.

In How to Talk About Books You Haven’t Read, the writer Pierre Bayard says that although we’d like to “draw a clear line between reading and not reading,” in reality, this line is blurred. Bayard gives a fourfold classification of books:

- Books that are unknown to us

- Books we have skimmed

- Books we have heard of

- Books we have forgotten

Bayard avoids including a category for books we have actually read. After all, what does it mean to say we have read something? That we have memorised every word? That we have a general sense of what the book is about? Or something else? Bayard writes, “What we take to be the books we have read, is in fact an anomalous accumulation of fragments of texts, reworked by our imagination.”

This is even true of the things we have ourselves written. Thinking back on my own books, I realise that most of what I’ve written I’ve now forgotten. Human memory is frail. So while I can give you a general sense of what these books are about, and I can tell you a couple of stories from each of them, I probably misremember as much as I remember (this is why picking up books you have written a decade later can be both surprising and sometimes uncomfortable).

If this is the case even with things we ourselves have written, what hope is there for getting to grips with, or exhaustively understanding, books by other writers? Even the simplest of books is a big, complex thing. It is the nexus of a whole bunch of relationships: with readers, with ideas, with other books, with other things. To thoroughly, exhaustively read a book would be to grasp the whole, complex set of relationships of which the book you are reading is a part. And that is impossible. Nobody has ever exhaustively or completely read a book. Not even the author.

So when we pick up Kant’s work, for example, out of necessity we find ourselves reading in ways he wouldn’t have read it—and perhaps couldn’t have read it. There is no such thing as a non-idiosyncratic way of reading (even if some idiosyncrasies are deemed more socially acceptable than others, for good reasons or ill).

Readers and purposes

If there is no single, preordained “right” way to read a book, and no way of exhaustively reading a book, this means that as a reader, you have the right to read however you like. So why not experiment with all the wrong ways that you can read? Why not embrace the messy, haphazard complexity of our relationship with the written word, and find your own way, free of obligation?

But at this point you might protest: surely there are better and worse ways of reading Plato, or Kant, or Hannah Arendt? Well, maybe. But the question here is better or worse for what? How we read is intimately related to why we read. It is a matter of our intentions and interests. If there is no single best way of reading a philosophy book, this is because we read philosophy for different purposes and to different ends. And getting clear about these purposes and ends can open up new ways of reading.

But that’s a topic for the next article in this series, where I’ll be asking what it means to read self-interestedly.

Read the whole series on seven ways of reading philosophy…

- Reading Napoleonically

- Reading haphazardly

- Reading self-interestedly

- Reading out loud

- Reading drunkenly

- Reading for laughs

- Reading with others (forthcoming!)

Notes:

Daniel Pennac (trans. Sarah Ardizzone), The Rights of the Reader (Walker Books 2006).

Pierre Bayard (trans. Jeffrey Mehlman), How to Talk About Books You Haven’t Read (Bloomsbury 2007).

There’s a great poster from Walker Books, which shows all ten of these rights.

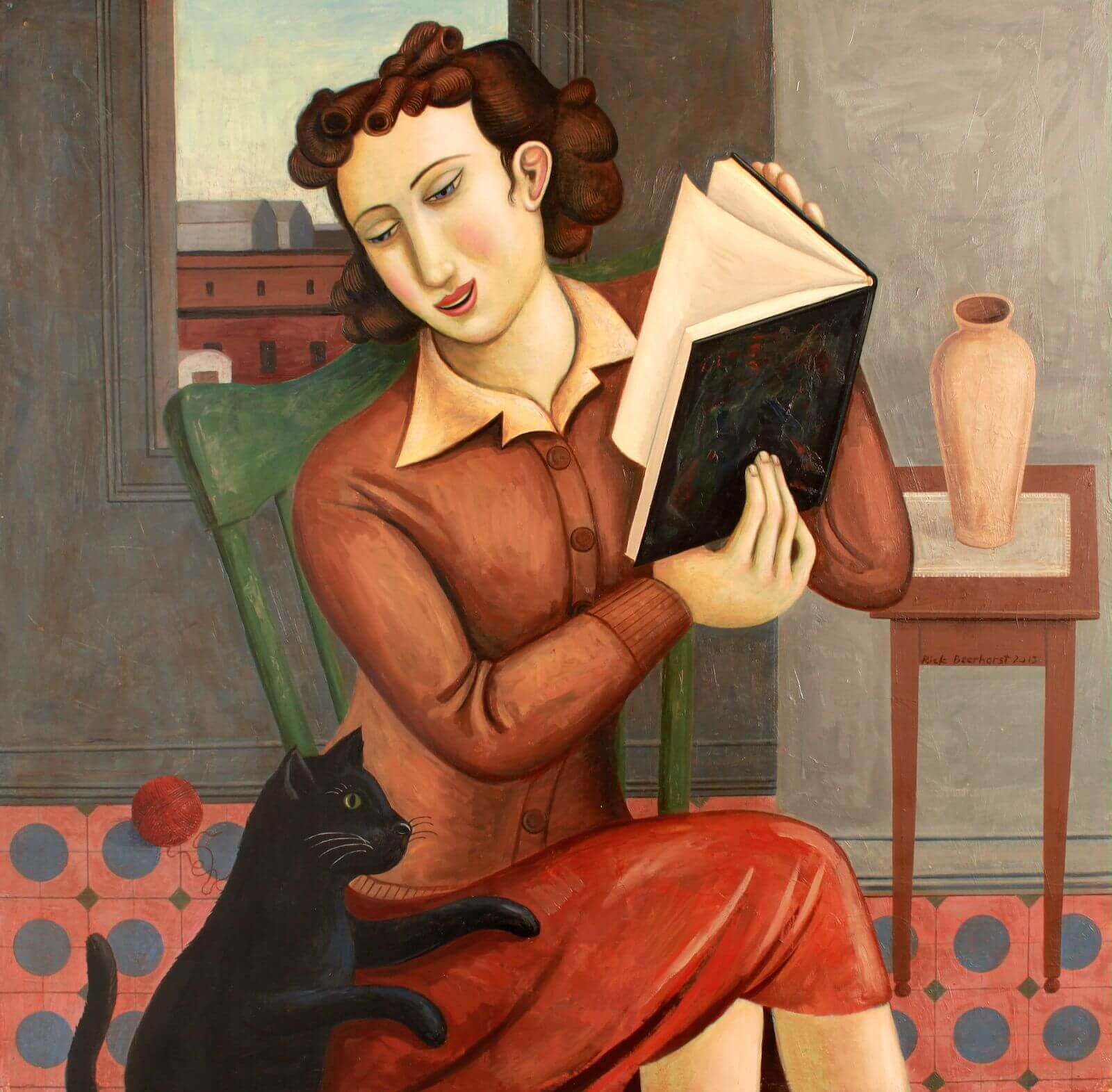

Image: The Distracted Reader by Rick&Brenda Beerhorst. Creative Commons 2.0 licence via Flickr.