When reading philosophy, the advice is often to read slowly and carefully, tortoise-style, making sure you understand every point before going on to the next. But in this article — the second in my ongoing series on how to read philosophy — I want to persuade you that this can sometimes be the very worst approach. And to do so, I’m going to take my lead from the German philosopher Franz Rosenzweig (1886-1929).

How to read better

Rosenzweig is a fascinating thinker. His most famous book is The Star of Redemption, which he started writing while he was serving in the German army on the Balkan front. He sent the text back home scribbled on army postcards and completed the book after the war ended. The book was published in 1921. Rosenzweig intended it to be a new way of doing philosophy, based in what he called Sprachdenken, or “speech-thinking,” a kind of thinking that is closely related to storytelling. But after it was published, Rosenzweig’s book was met with general incomprehension. So in 1925, Rosenzweig wrote an essay called The New Thinking, where he tried to explain what he was up to. And along the way, he made a fascinating argument about how we read philosophy (including his own book) all wrong.

In his essay, Rosenzweig argues that when we read philosophy, we make the mistake of imagining that what we are reading is “especially logical.” We imagine that the ideas in the text will follow each other in neat chains of reasoning, with each sentence leading on to the next. We think that if we start at the beginning and work through systematically, making sure we understand every sentence before moving on to the next, we’ll get the hang of what is going on. But the reality is, “Nowhere is this less the case than in philosophical books.”[1] For Rosenzweig, there is something story-like about how we come to understand philosophy. We start at the beginning, sunk in confusion and mystery. And clarity only emerges as the story unfolds. This is how Rosenzweig puts it:

Here [i.e. in philosophy books] a sentence does not follow from the preceding one, but more likely from the one following. Whoever has not understood a sentence or a paragraph is little helped if, in the conscientious belief that they must not leave anything behind that is not understood, they read it again and again or even start over again.

Instead of reading carefully, understanding each sentence on the basis of the one before, Rosenzweig suggests a different approach. We should charge ahead, he says. Philosophy books, “want to be conquered Napoleonically, in a bold attack on the enemy’s central force, upon the conquest of which the small outlying fortifications will fall automatically.”

Or, as he puts it a couple of pages later, when reading philosophy, “Above all: rush! Do not stop!”

Pitting our wits against Wittgenstein

Let’s take an example. Like The Star of Redemption, Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus started life when its author was drafted into the army in the First World War. But other than this, the two books couldn’t be more different. Rosenzweig’s book seems dauntingly elliptical. In contrast, the Tractatus seems like a model of good order. With its tidy numbered paragraphs, it certainly looks clear and logical.

And yet, if you launch in and read through the first half of the first page—particularly if you are new to philosophy—things soon become pretty perplexing.

1.The world is all that is the case1.1The world is the totality of facts, not of things.1.11The world is determined by the facts, and by their being all the facts1.12For the totality of facts determines what is the case, and also whatever is not the case.1.13The facts in logical space are the world. [2]

“The world is all that is the case…” Okay, you think. This kind of makes sense. So you go to the next paragraph, which seems to be a comment on the first.

“The world is the totality of facts, not of things” (1.1). But, you ask yourself, what are “facts” and what are “things”? It’s not clear, at least not yet. You shrug and press on to the next paragraph, which seems to be a comment on the paragraph before.

“The world is determined by the facts, and by their being all the facts” (1.11). Has this made things clearer? Or has it made them muddier? It’s hard to be sure. But, hold on…! What’s next?

“For the totality of facts determines what is the case, and also whatever is not the case” (1.12). You think this might be saying something new. But then again, it might be saying the same thing differently. It’s hard to tell.

Next you read, “The facts in logical space are the world” (1.13). By now, you are fewer than sixty words in, and you are already baffled.

At this point, the temptation might be to go back to the beginning, and read these sixty words again, or even to read them repeatedly until they make some kind of sense. After all, if you can’t understand the first sixty words, what chance do you have of understanding the next sixty, and the sixty after that? But, taking advice from Rosenzweig, this is almost certainly the wrong approach. Instead, when you start to get bogged down, it is precisely then that you should put on your Tricorn hat and gallop onwards, as Napoleon would.

Remember this: Above all, don’t stop!

And then, once you pick up the pace of the reading, you start to find that things fall into place. For example, when you know that for Wittgenstein “What is the case—a fact—is the existence of states of affairs” (proposition 2), this throws light on proposition 1.1 (“The world is the totality of facts, not of things”). And once you know that “We picture facts to ourselves” (proposition 2.1), you can make more sense of what Wittgenstein means when he talks about facts, and when he talks about the world.

So on you gallop, until you get to the famous final proposition, “What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence” (proposition 7); and at this point, if your Napoleonic campaign is successful, the light will have come on. “Aha!” you say to yourself. “So that’s what Wittgenstein is up to!”

Philosophy at a gallop

But this article isn’t really about Wittgenstein. Instead, it is about how to read philosophy. And for Rosenzweig, reading philosophy fast, reading it at a gallop, is often the very best way. Rosenzweig writes:

Thus, whoever does not understand something can most assuredly expect enlightenment if they courageously go on reading. The reason why this rule is difficult for the beginner, and […] also for many a non-beginner to accept, lies in the fact that thinking and writing are not the same. In thinking, one stroke really strikes a thousand connections. In writing, these thousand must be artfully and cleanly arranged on the string of thousands of lines.

Remember that for Rosenzweig, the way that philosophical arguments unfold is a kind of “speech thinking.” Philosophy is a kind of storytelling. Like stories, philosophical arguments unfold with a beginning, middle and end. And it is only when you can see all these different parts that you can make sense of the whole.

When you read a story, you know that at the beginning you are not going to know what is happening. You may be lost, intrigued, baffled or fascinated. But you probably won’t have full comprehension. That is the point of a story. And that’s the fun of it too. So you keep on reading because you know that it is only when you get to the end of the story (“What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence”) that you will be able to see how the whole thing fits together. __

So when reading philosophy, and when things seem difficult and make no sense, this is the time to mount your horse and head into the fray, overflowing with fearless energy.

But, you might ask, what if you get to the end of the _Tractatus—_or any other philosophy book—and find you have galloped out the other side without any of the major fortresses falling? What if you get to the end, and are still as baffled as before?

Well, that’s fine too. Because nothing is lost. You and your horse have had a good work-out. The ride has been exhilarating. Even though you have failed to understand, but haven’t wasted hours in failing to understand. And when you go head back into the enemy territory at a later date, ready to launch a more strategic attack on those philosophical fortresses, you will do so with a stronger sense of the lie of the land.

Read the whole series on seven ways of reading philosophy

- Reading Napoleonically

- Reading haphazardly

- Reading self-interestedly

- Reading out loud

- Reading drunkenly

- Reading for laughs

- Reading with others (forthcoming!)

Notes

[1] This, and all subsequent passages by Rosenzweig, come from Barbara Galli and Alan Udoff, Franz Rosenzweig’s “The New Thinking” (Syracuse University Press 1999), pp. 71-3.

[2] This, and all subsequent passages by Wittgenstein, come from the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus ( Routledge 2001), p. 5.

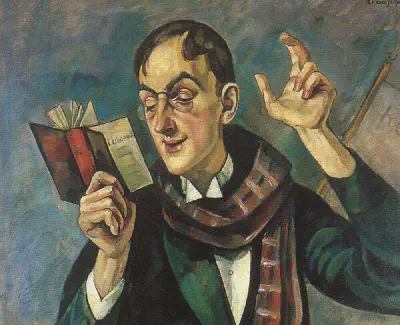

Image: Jacques-Louis David: Napoleon Crossing the Alps (1801), Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.